Looking out of the barred window of the tiny cell that Oscar Wilde occupied between 1895-97 as prisoner number C33 while serving his sentence for committing “acts of gross indecency with other male persons,” it was incredibly moving to experience first-hand on a glorious sunny day “that little tent of blue/Which prisoners call the sky”, described so vividly in Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898).

This unprecedented opening of Reading Prison, which was only decommissioned in 2013, has come about due to the ever-enterprising and indefatigable Artangel. The non-profit managed to persuade the Ministry of Justice to grant it permission in order to mount an extraordinary group exhibition inside what is now, thanks to its most famous occupant, a world famous institution.

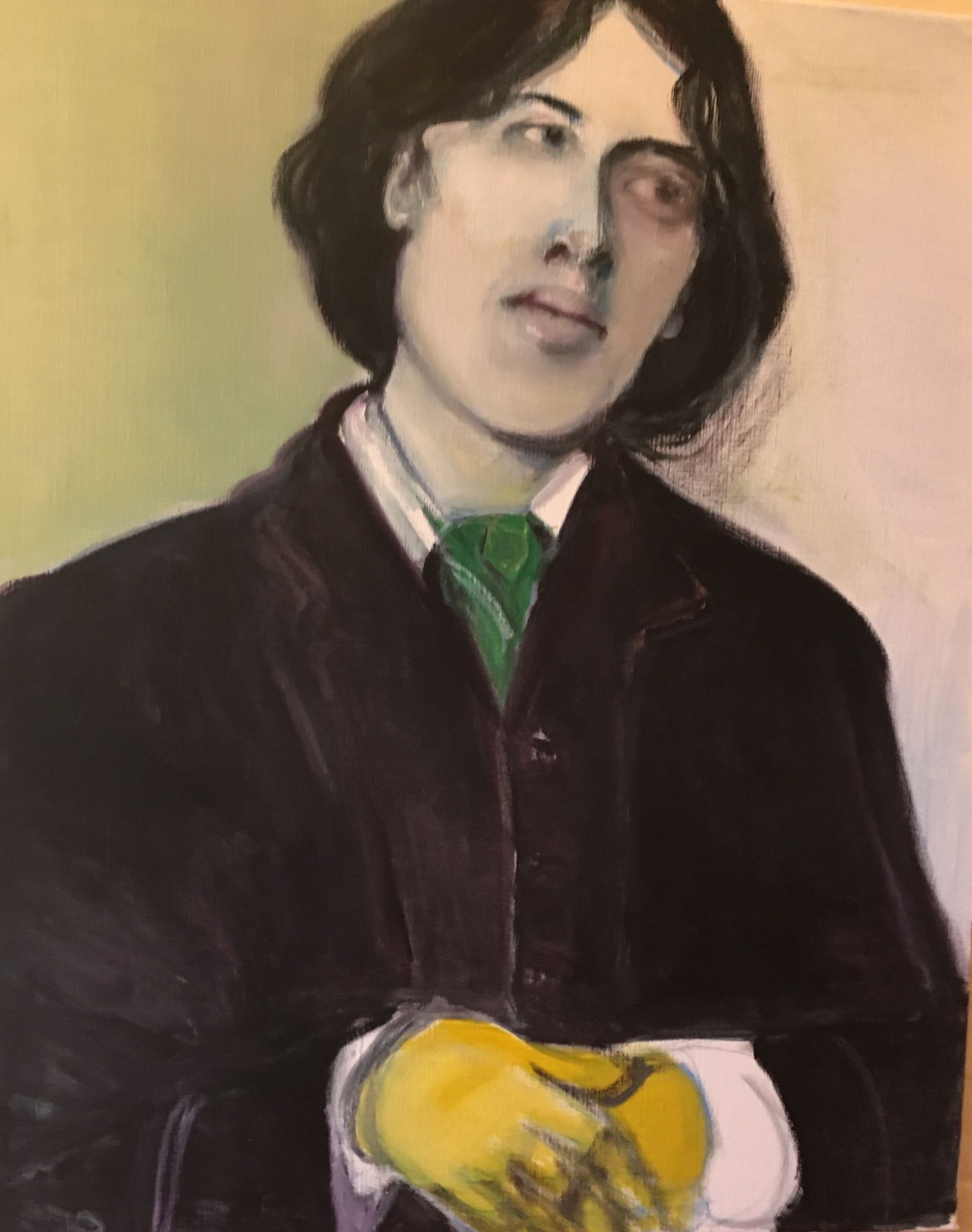

Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison (4 September-20 October) is a rich and multi-layered project in which an amazing array of artists, performers and writers have been invited to respond in-situ to the writing of Wilde, the environment of the prison and themes of incarceration and separation. Among the works in the individual cells—that still bear the graffiti and stains of more recent occupants—are new paintings by Marlene Dumas, including spectral portraits of Oscar and an especially shifty Bosie as well as a tragic-eyed Jean Genet. Wolfgang Tillmans has created warped self-portraits reflected in a prison mirror, while a new sculpture by Steve McQueen canopies a shabby prison bunk with a disconcertingly blingy gold-plated mosquito net.

Nan Goldin’s various explorations of obsession and desire include covering almost every surface of one cell with drifts of photographs of a beautiful German actor, as well as making you peer through a peep hole in a door at a projection of Un Chant D’Amour (1950), Jean Genet’s film of erotically-charged encounters between two gay prisoners in adjacent cells. Doris Salcedo stacks coffin-like tables sprouting blades of grass at the end of a murky corridor, while Robert Gober bores into the fabric of the building to produce an uncannily limpid waterfall framed by the back of a coat jacket and a battered wooden chest on the floor, offering a deep view of a river bed contained within the prone torso of a woman.

Life, death, the confines of the body and the escapist power of the imagination are all conjured here. In the chapel, Jean-Michel Pancin takes Wilde’s original wooden cell-door and mounts it like a free standing gravestone on a low concrete plinth exactly the same size as his cell, which is just down the corridor.

You can also sit in more cells reading and/or listening to nine letters composed by contemporary writers to a loved one from whom they have been separated. Deborah Levy writes to Wilde himself and decries our time-honoured brutalisation of men and boys. Ai Weiwei’s gruelling and affecting account of his own treatment at the hands of the Chinese authorities ends with the compassionate realisation that his omnipresent guards are in fact more imprisoned than he.

Yet amidst all these remarkable works, and along with the brutal evidence of Oscar’s incarceration, what affected me just as much was the knowledge that until three years ago Reading was a fully operational prison, and in later years for young male offenders aged between 18 and 21. Due to prison overcrowding it is very likely that often two, or sometimes even three, inmates would have occupied Oscar’s cell. In this now-silenced prison, it was the unheard voices of these young men—whose messages, stickers and bodily fluids still stain the 19th-century walls and surfaces—that rang most loudly in my ears.