I have mixed emotions about the auction of works owned by the late art critic Brian Sewell at Christie’s that takes place on 27 September. The collector in me is excited to witness the dispersal of a largely unknown treasure trove of Old Master and 19th-century pictures and drawings, hidden from the market for 40 years or more. But as a friend of Brian’s for over 25 years, it will be sad to say goodbye to things that I always enjoyed when visiting him in Eldon Road in west London. Here, framed drawings hung floor to ceiling in the hall, and other works, framed or not, were stacked across library shelving, their edges softened by a layer of dust.

Unlike many collectors, Sewell seldom talked about his treasures—they were just things he had around and you had to be interested enough to draw him into discussing them. Even then, he almost never mentioned where he had found them or the dealer they had come from. Often, as he peered over your shoulder into drawers of unframed drawings from Abraham Bloemaert (1566-1651) to Maxwell Armfield (1881-1972), he would point something out and say: “I don’t know who did it and I don’t really care. But isn’t it beautiful?”

Rococo-free zone His taste was broad, encompassing everything from 16th-century Italian Mannerist drawings to 20th-century British paintings. He admitted to having little interest in the Rococo, particularly in 18th-century France, and it is telling that the most beautiful 18th-century French picture in his collection is the antithesis of the movement: an exquisite proto-classical copper of Charity by Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée (1724-1805, not at auction in September).

After he moved to a bigger house in Wimbledon, southwest London, his collection was spread out a bit and more neatly displayed, but there were still discoveries to be made. A casually opened drawer revealed a monumental black chalk of Dido Reclining, Asleep, by Daniele da Volterra (1509-1566), which he had owned since 1963 and had never bothered to get framed (est £50,000-£80,000), and a double-sided oil sketch by Tintoretto (1560-1635), as big as the top of a bridge-table (est £15,000-£20,000).

He sometimes discussed his collection with the same irreverence that infused his reviews. When I admired an extraordinary Fuselian Cupid and Psyche (1785, est. £12,000-£18,000) in clouds of yellow varnish (he hated picture restorers and had nothing cleaned), by the usually stolid portraitist John Hoppner, he wryly giggled: “Yes… Isn’t it awful?”

In both his homes, Sewell’s beloved egg tempera paintings by his friend Eliot Hodgkin were always on view (12 Hodgkin works are on offer at Christie’s). He always had his favourite, Three Kohlrabi (1961, est £15,000-£25,000), overlooking his aged, manual typewriter.

He seldom lent to exhibitions. The last loans, to my knowledge, were two of his treasured paintings by Matthias Stom (or Stomer) to the Barber Institute’s Stom show in 1999, including Blowing Hot, Blowing Cold (around 1628, est £400,000-£600,000) and his pen drawing of a dejectedly slumped male nude by James Barry (1741-1806, est £20,000-£30,000) to the artist’s 2005 retrospective at the Crawford Art Gallery, Cork. But whenever he did, it inevitably elicited the reaction of “Brian Sewell—owns that?”

• The 250 works in the Brian Sewell: Critic and Collector auction, which is scheduled to be held on 27 September, at Christie’s King Street saleroom, London, have estimates ranging from £1,000 to £600,000, adding up to a total of around £2m. Sewell died, aged 84, in September 2015.

A present, a passion and a puzzle: three under the hammer Andrea Sacchi (1599-1661)

The Madonna and Child with Saints Ignatius of Loyola, Francis Xavier, Cosmas and Damian (1629)—a bozzetto

Est £50,000-£80,000

In 1966, the Sunday Telegraph Magazine ran a feature in which various art experts were each given £200 and asked to account for how they spent it. Sewell chose this beautiful, finished bozzetto, or sketch, by Sacchi, a preparatory study for a fresco in the Collegio Romano Soffitto della Spezieria in Rome. Sacchi’s easel paintings are extraordinarily rare and this sketch is one of the artist’s last works to have been privately owned. Sewell made little fuss over it, hanging it high in his library in his home in Leopold Road in Wimbledon.

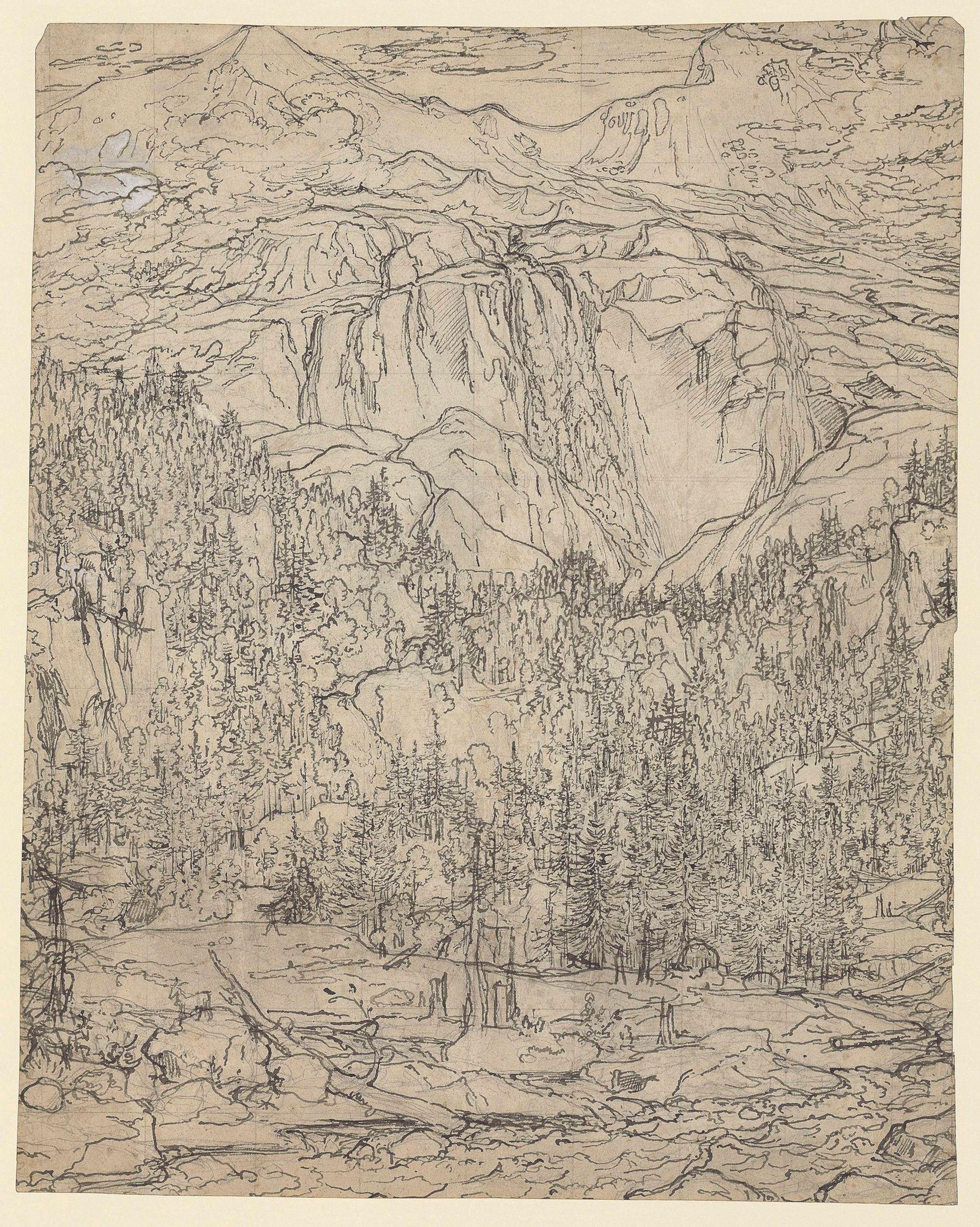

Joseph Anton Koch (1768-1839)

The Schmadribach Waterfall near Lauterbrunnen, Switzerland (recto); a faint sketch of a mountainous landscape (verso)

Est £20,000-£30,000

Sewell was always an advocate of German art (Wagner sung by Kirsten Flagstad and Lauritz Melchior was his musical passion) and often bemoaned the reluctance of British museums to pursue it. He made a point of buying drawings by Germans whenever he could and, fortunately for him, most were absurdly cheap in the 1960s and 70s. This pen and black chalk study of a waterfall is a highly important cartoon by Koch for The Schmadribach Waterfall near Lauterbrunnen, his most important landscape painting—now in the Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig. There are no drawings by Koch in the British Museum.

Agostino Ciampelli (1565-1630)

A soldier carrying a ladder, and a subsidiary study of a man holding a torch (recto); faint fragmentary study (verso)

Est £20,000-£30,000

Many of Sewell’s works were puzzles for Christie’s team. This large and handsome sheet of remarkable quality was bought as a work by Federico Zuccaro, then attributed by Sewell to Giovanni Lanfranco. After much research it has now been definitively identified as a study by the late 16th-century Florentine Agostino Ciampelli (1565-1630) made for a canvas of The Duke of Guise attacks Calais in 1558, and part of the outdoor decorations for the 1589 wedding of the grand duke Ferdinando I de’ Medici (1549-1609) and Christine de Lorraine (1565-1637). The painting was destroyed in a fire at the Pitti Palace, but the composition is known from two contemporary engravings.