I’m not sure if all the Peckham cineastes who frequent the panoramic cinema club screenings on the roof of the Bussey Building at 133 Rye Lane, realise that the adjacent building used to house one of London’s earliest cinemas: the 400-seater Electric Theatre, which opened in 1908. Now poised for redevelopment into (hopefully reasonably priced) studios and shared workspaces, its cavernous space is once again playing host to moving pictures, albeit of a more artistic nature.

Currently showing until 9 October is Artangel’s presentation of The Colony, a new three-screen film installation by the Vietnamese artist and film-maker Dinh Q. Lê. The work provides a panoramic but also somewhat disconcerting immersion in the desolate environment of the Chincha Islands off the coast of Peru. These islands were once among the most prized and contested places in the world due to the mountains of guano deposited by their vast seabird populations. On account of their miraculous properties as fertilizer, the deposits sparked the great 19th-century Guano Rush across Europe and North America. Spain, Peru and Chile even went to war over the islands while the US passed legislation authorizing what amounted to a wholesale guano island land-grab.

The frenzy abated with the development of chemical fertilisers at the beginning of the 20th century. But these days the guano is popular with organically-minded gardeners and still gruellingly mined in a back-breaking way by Peruvian labourers. Many of them are the descendants of the country’s ancient indigenous peoples who first used the bird manure to render their land fertile and build their civilizations.

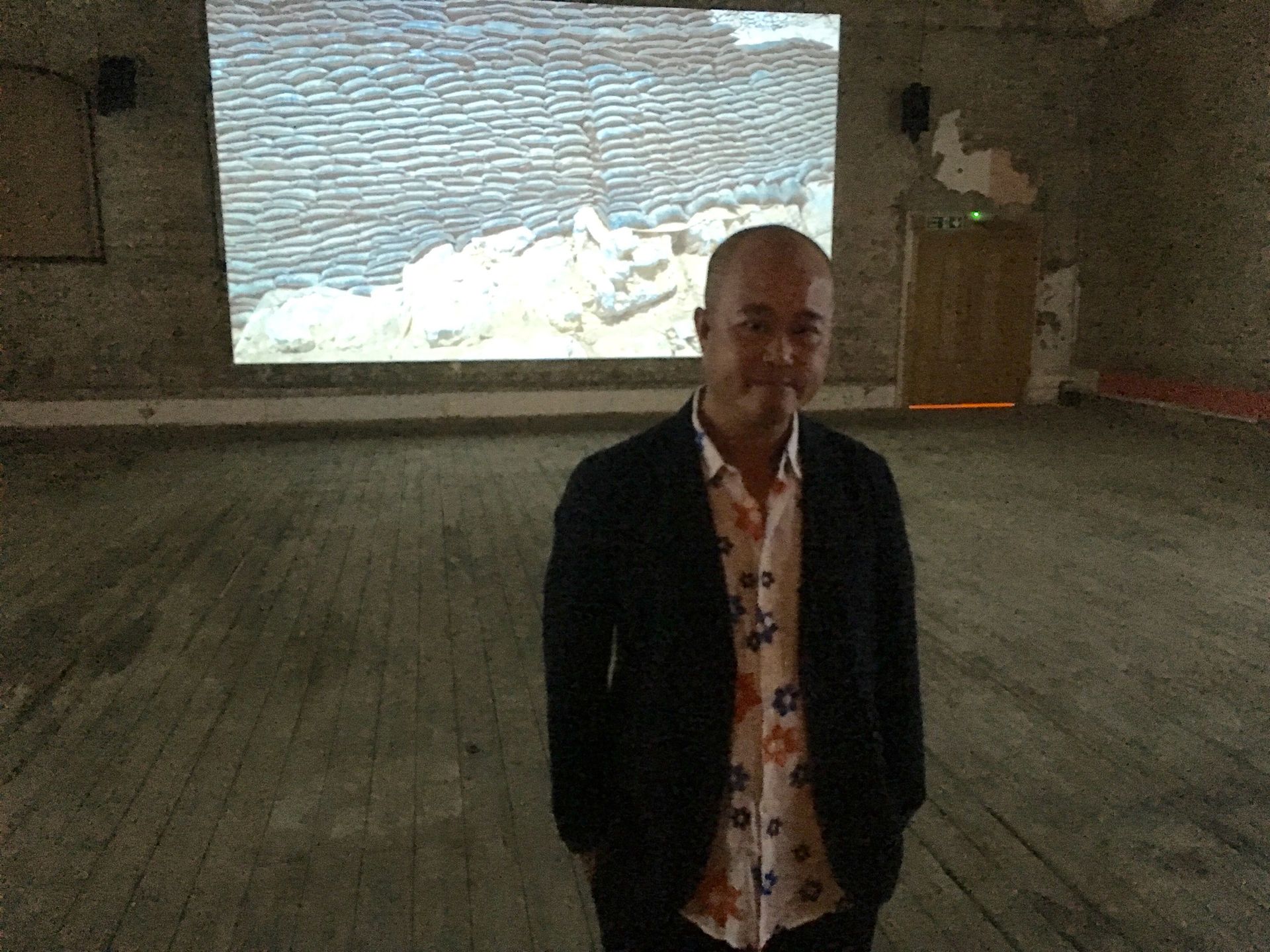

Dinh Q. Lê was initially attracted to the role of the guano islands in opening up the Pacific to US and European interests, which set in motion the events ultimately leading to the Vietnam war and its consequences. This then directly impacted the artist, who escaped Vietnam by boat in the 1970s. He also sees a circularity in the 19th-century use of indentured Chinese labour to harvest the guano and China’s current colonial incursions into the South China Sea. Ancient meets modern in Lê’s film, which offers a bird’seye view of the islands and its labourers, achieved with the use of some ominous-looking drones.

But although he shows the labourers scooping up the malodourous commodity in their bare hands, manually building epic pyramids and ziggurats of the bagged-up poop, there is little sense of the punishing conditions in which this valuable commodity is produced. This was in great part because the Peruvian government, who own the islands and manage the workforce, would not permit the artist and his crew to film their accommodation or speak to any of the workers. “If we’d been allowed to talk to them the film would have been very different,” Lê told me, adding the grisly detail that the worker’s hardship is amplified by the fact that the island is crawling with ticks. Apparently these were introduced in the 19th century when cows were brought in as a food and milk supply. And when the cows left, the ticks didn't. Unfortunately, the birds haven’t developed a taste for them but Lê is threatening that these deeply unappealing bugs may appear in a future film, whether or not he is allowed to speak to the workers.