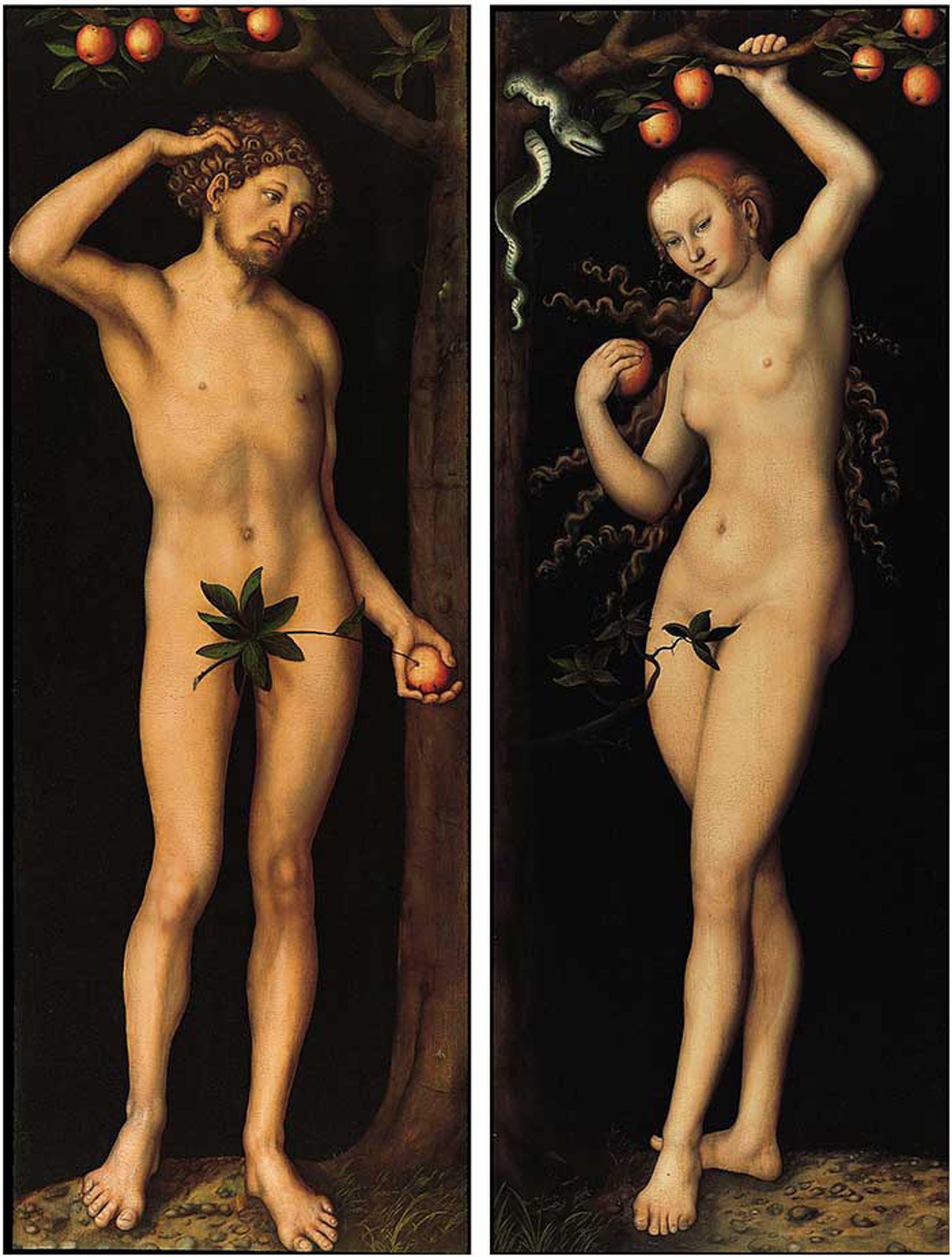

A judge in US District Court in California has dismissed a claim by an heir to the Dutch dealer and collector Jacques Goudstikker to recover Lucas Cranach’s Adam and Eve (around 1530), two paintings now at the Norton Simon Museum.

The 15 August ruling in the decade-long case holds that the paintings became the property of the Dutch government after the Second World War. Judge John Walter faulted the Goudstikker family and the firm that handled its post-war affairs for failing to meet mandated deadlines for filing an ownership claim to the pictures. The heir who brought the claim against the Norton Simon, Marei von Saher, intends to appeal, her lawyer said.

The Jewish collector and dealer Jacques Goudstikker bought the Cranach paintings at a 1931 auction in Berlin of works “from the Stroganoff Collection” supplied by the Soviet government. Goudstikker fled the Netherlands in 1940 and the works were then sold under duress to Hermann Göring during the Nazi occupation of the country, but were returned to the Dutch state after the war.

In 1961, the exiled Russian aristocrat George Stroganoff claimed that he was the rightful owner of four paintings in Dutch hands—the Cranachs, a Rembrandt and a Petrus Christus—which he said had been seized by the Soviets after the Russian Revolution. According to von Saher’s claim, the works were instead taken by the Bolsheviks from churches in Kiev. The Dutch government sold the Cranachs and the Petrus Christus to Stroganoff in 1966 for 60,000 guilders, after he waived any title claim to the Rembrandt. The collector Norton Simon then bought the Cranachs from Stroganoff in 1971 for $800,000. The Pasadena Museum of Modern Art was renamed for Simon in 1975.

The Norton Simon Art Foundation, which oversees the museum’s collection, said it was happy with the ruling. “The Court’s decision is based on the merits, considering the facts and law at the heart of the dispute,” the foundation said in a statement issued Tuesday night. “The Norton Simon takes seriously the fiduciary responsibility to the public that our ownership of such important artworks confers. We have placed the panels on near-constant public display since 1971 and will continue to ensure they remain accessible to the public for years to come.” The museum issued a more extensive statement of its position in the case last year.

Marei von Saher’s lawyer, Larry Kaye, said that his client was disappointed by the decision but “remains undaunted and is optimistic that she will prevail in the end”, and she plans to file an appeal. “Over the many years that she has sought justice for the theft of Jacques Goudstikker’s property by the Nazis, Ms von Saher has been gratified by her many successes, especially when those in possession of her artworks have done the right thing and returned the works to her without her having to resort to litigation,” he wrote. In 2006, the Dutch government returned 202 paintings from Goudstikker’s collection to von Saher.

“There’s no disputing the actual provenance,” said E. Randol Schoenberg, a lawyer who consulted on the case for Von Saher and previously helped Maria Altmann recover her family’s art from the Austrian government. “If these paintings never go back, there’s a real problem in how we deal with Nazi-looted art.”