A conference on Henri Matisse at the Barnes Foundation scheduled for 13 to 15 October will bring scholars to Philadelphia to discuss the artist’s continuing legacy. A series of lectures and panels will look at topics like the artist’s interest in non-Western art and will include speakers such as the historians Claudine Grammont and Helene Ivanoff.

“Our goal is to assess the state of our knowledge on Matisse today and to outline what could be done next in terms of future study, research, exhibitions, and collections,” says the conference’s organiser, Sylvie Patry, the Barnes's deputy director and chief curator. “I think it is always fascinating for the general public to understand that even with such a famous artist like Matisse, scholars always find new ways to look at his work.”

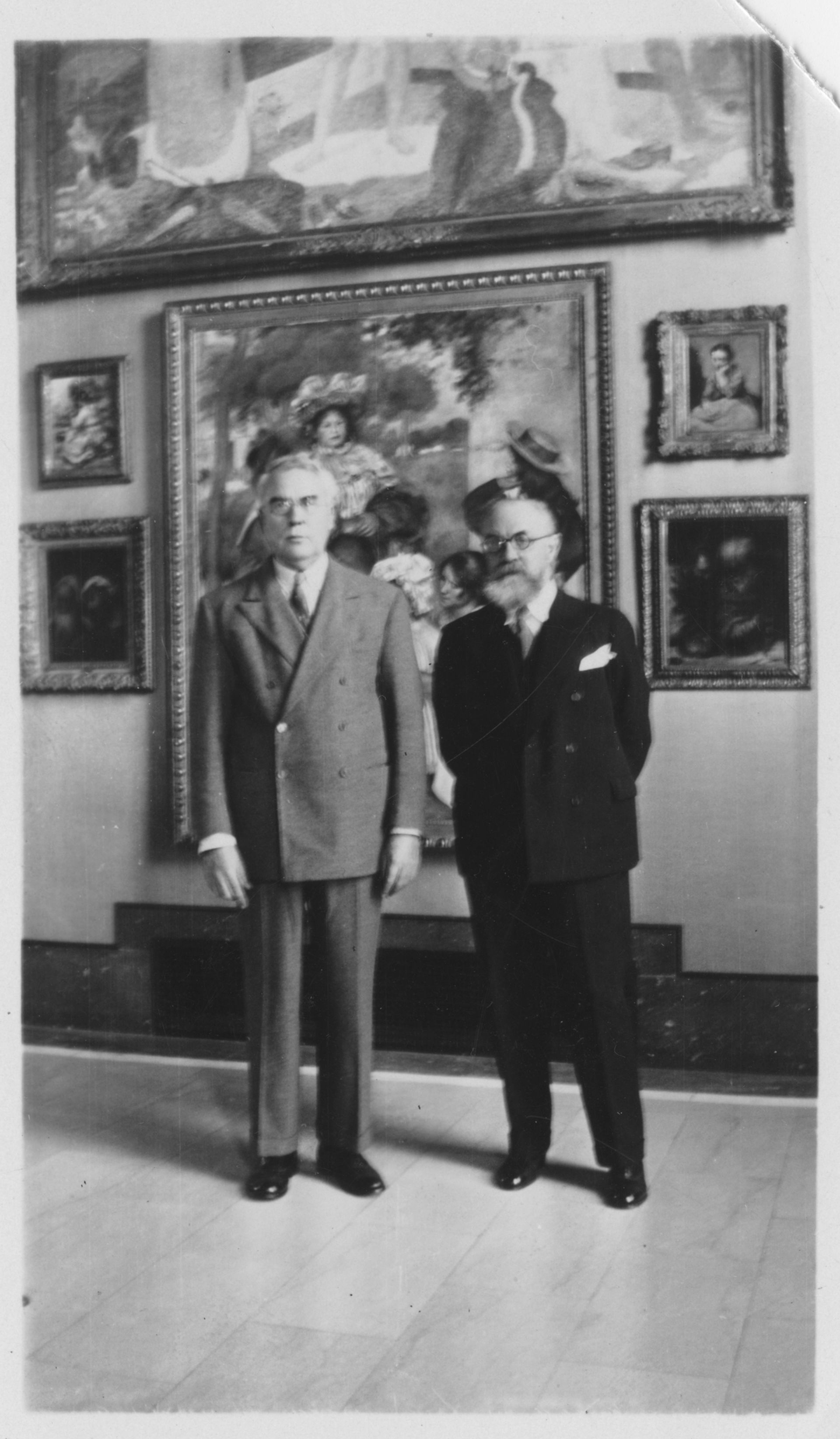

The Barnes has a long association with Matisse. In 1912, its founder Albert Barnes bought his first two works by the artist, the paintings The Sea Seen from Collioure (1906) and Dishes and Melon (1906-1907). Over the years, Barnes continued to support Matisse’s work and invited him in 1930 to paint a canvas triptych mural for three arches at the foundation’s home outside Philadelphia in Lower Merion, Pennsylvania. The project, which was completed in 1933, cost Barnes $30,000 and reinvigorated Matisse, whose work had lagged during his years in Nice between 1917 and 1930, says the art historian Yve-Alain Bois. Bois, who edited the book Matisse in the Barnes Foundation published by Thames and Hudson in January, will also deliver the conference’s keynote lecture.

“In the Nice period, [Matisse] was very frustrated, because he had been surpassed by Picasso as a champion of the avant-garde, and so he retreated,” Bois says. “The end of the 1920s was a difficult period for him. He was bored to death by his Odalisque paintings, even though they were very successful on the market. When the Barnes commission arrives, he is offered a great surface to decorate and suddenly he is plunged back into his youth.”

The Barnes commission freed Matisse from the rigidity of his Nice style. “His sketches for The Dance are extraordinary because they are just a few strokes,” Bois says. “There is absolutely no description, they’re just schematic indications of the movement of the dancer. He realizes he doesn’t have to be so guarded. In the early 1930s there is definitely a change in the way he understands drawing and painting and he starts to value work that is not completely controlled.”