Auguste Rodin died in November 1917 as war continued to rage in Europe. He had achieved acclaim and gained many friends in the UK, but because of the war, British mourners were unable to travel to France, so a memorial service was held in London. It took place at St Margaret’s Church, next to Westminster Abbey, on 24 November. From there, the mourners crossed the road to pay tribute at The Burghers of Calais, the multi-figure bronze sculpture standing in Victoria Embankment Gardens, close to the Houses of Parliament. Two wreaths were left by the distinguished group of mourners. One was from Her Majesty’s Government; the other, with lilies of the valley and carnations, was inscribed: “To my dear master in friendship and deep homage from your model and friend, Julia”.

Julia was one of the names adopted by the English actress Sybil Mignon Cooke, who Rodin had met in 1907. Then aged 66, he began a relationship with the 21-year-old Cooke (1886-1973). Their affair is revealed in letters that have just been acquired by the Musée Rodin in Paris. The papers came from her descendants, with the sale arranged by the London dealer Bowman Sculpture. Rodin’s love for the young actress is another reminder of the sculptor’s close links with Britain. Called Mignon by her family, Cooke was renowned for her “lovely voice, striking looks and witty charm”, according to Ben Hunter, who researched and handled the Bowman sale. Acting under the stage names Viola or Julia/Juliette, she performed in Berlin in 1907. Later that year she travelled to Paris, where she met Rodin, who was then Europe’s most distinguished sculptor.

Youth in all its beauty Cooke quickly agreed to model. The result was at least seven drawings, either standing in the nude or holding a veil. These were kept by Rodin and are now in his museum. After the session, Rodin wrote to Cooke: “Alas, my voluptuous memory does not manage to capture you; that adorable form of your youth in all its beauty which demanded my adoration as an artist and a man... I kiss your hands and very secretly your beautiful portrait.”

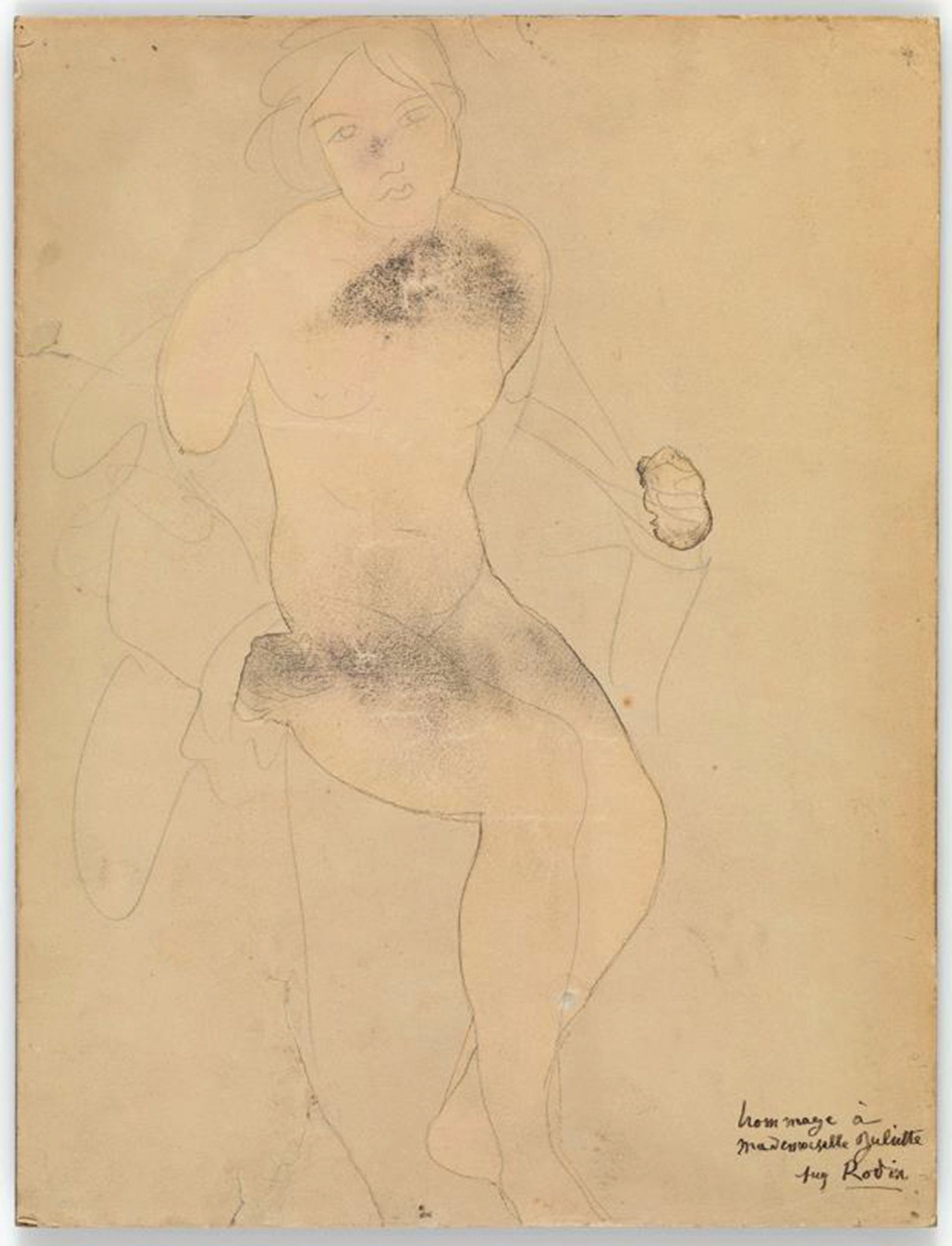

Rodin gave Cooke two of his works. One was a drawing of a young woman opening her dressing gown, inscribed Hommage à Mademoiselle Juliette. The Rodin specialist Christina Buley-Uribe (author of My Divine Sisters, a book on Rodin’s women) dates it to about 1900—in which case it cannot depict Cooke. However, it would have been more likely for Rodin to have given the actress one of the drawings he made of her (the facial features in the one presented to her are not clear enough to identify the sitter). The second gift was a plaster maquette of a relief of a female bust, not based on Cooke. Rodin also gave her his photograph.

At the end of 1907 Cooke returned to Berlin and they kept in touch. She wrote to thank Rodin for his gifts: “I still have in my bedroom your dear portrait [the photograph] and the small plaque... They are the most precious things that I possess.” The following year Rodin sent her a telegram, saying he would be delighted to see her if she returned to Paris. Whenever Cooke travelled from Berlin to her parents’ home in London, she would stop in the French capital and pose for Rodin. Once in 1909 they spent the day together, including a lunch. In her diary Cooke described how they ate at a Duval restaurant “like students”.

Cherished thoughts On another occasion they went shopping, with Rodin buying her silk stockings, two blouses, gloves and a hat. Cooke wrote in thanks, saying “it was so fun to choose these little items”, signing off “your devoted little Viola”. Rodin gave her another photograph of himself, signed with “affectionate homage and devotion”. After another meeting, Cooke wrote to Rodin: “These are hours I will keep always in my most cherished thoughts.” In 1911 Cooke implored Rodin to visit her in Berlin: “If you want to work with me, all my time would of course be dedicated to you if you wished. Maybe we could even do a little statue or statuette together—or if not I could sometimes come and watch you work—ah, that would be so nice!” Rodin spoke no English, so they communicated in French.

In June 1913 Rodin was visiting London for the installation of The Burghers of Calais, and Cooke invited him to her parents’ home in Argyll Lodge. Photographs of Rodin were taken in the garden. (We reproduce one for the first time.) It was their last meeting. In her final letter to Rodin, in 1917, Cooke recalled her visits to his studio as “the happiest hours of [my] life”. On 2 October 1917 she married Robert Hood. Six weeks later Rodin died.

We will never know the exact nature of their relationship. Buley-Uribe has described it as “friendly intimacy” and Hunter maintains that it is “dangerous to assume anything about their relationship”. But Rodin was enchanted by Cooke and adored her youthful body; she could hardly have been more adoring, pleading with him to allow her to pose. No doubt his fame and wealth attracted her, but it seems to have been deeper than that. Rodin is renowned for his affairs with models, including the sculptor Camille Claudel. It seems likely the aged sculptor and the young English actress probably did have some sort of affair.

After Cooke’s marriage, she had one son. Her married life appears to have been uneventful, at least compared with her acting career in her early 20s. She died in 1973, leaving the cache of documents to her son Robin. He died in 2010, and earlier this year the papers were bought by the Musée Rodin. Cooke never talked publicly about Rodin, but she nevertheless carefully preserved his letters. We do not know if this was in recognition of their historical significance or because of her intimate feelings for the great sculptor.

How War Defined Rodin’s affection for Britain Rodin’s legacy in Britain was inextricably bound up with the First World War. In July 1914 Rodin was in London for his display at the Grosvenor House exhibition of contemporary French art. War then broke out and it seemed risky to return the 18 sculptures he showed. In September that year, Rodin managed to travel to London. A highlight was lunch at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A); he particularly enjoyed English beer in the grill room. Two months later Rodin presented the 18 sculptures to the V&A in tribute to English and French soldiers who were fighting side-by-side “as brothers”.

The war also affected the unveiling of one of Rodin’s most prominent public sculptures. Though the National Art Collections Fund (now the Art Fund) paid £2,400 to buy the huge bronze of The Burghers of Calais (cast in 1905) in 1911, it took some time to erect. First there were disputes about where to place the work and then, once it was agreed that it would stand just outside the Palace of Westminster, war broke out. It was placed in Victoria Embankment Gardens in 1914, but its official unveiling was then postponed. Only on 19 July 1915 did this finally happen. (As The Art Newspaper revealed in November 2011, the bronze had been donated to the government’s Office of Works, and technically there was no owner when that body was disbanded after the Second World War. Following our report, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport announced it was assuming ownership of this extremely valuable work.)

Rodin eventually had numerous British friends, patrons—and lovers. His first attempt to break into the English market came in 1877, when he submitted a design for a monument to the poet Byron that was to be erected on the edge of London’s Green Park. The commission went to the now forgotten sculptor Richard Belt (his statue is marooned on a traffic island at Hyde Park Corner).

Rodin’s first visit to London was in 1881, and the following year and in 1884 he exhibited in the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition. But in 1886 his work Ixelles Idyll (1885), a bronze sculpture of two kissing infants, was turned down—much to his annoyance. In 1902 the first Rodin sculpture entered a UK public collection. St John the Baptist (1879) was acquired by the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A), with Rodin crossing the Channel for a celebratory dinner at the Café Royal in Piccadilly Circus.

The following year he was elected to succeed James Whistler as president of the London-based International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, set up to encourage Modern art. For the next few years he returned to England once or twice a year, including a visit in 1904 when he showed a large plaster of The Thinker (1904).

A year later he worked on a monument to Whistler, which was intended for Chelsea Embankment. Rodin did not produce a conventional statue, but an allegorical figure of a female muse “climbing the mountain of fame”. His model for the muse was Gwen John, the Welsh painter—and his mistress. However, the monument was never completed; in 2005 a statue of Whistler by Nicholas Dimbleby was erected on the site.

Sales to Britain began to flood in. In 1904, Edward Perry Warren, an American collector living in Lewes, East Sussex, commissioned a marble version of The Kiss. Warren, who was gay, specified that Rodin should “model the genitals as a Greek would have done”. Commissions then came in from aristocrats (the Countess of Warwick, Lady Sackville and Lord Howard de Walden) and celebrities (George Bernard Shaw and Arthur Balfour). In 1908, Rodin won royal approval when Edward VII visited his Paris studio.

But The Burghers of Calais was undoubtedly his biggest break in Britain—he was reportedly greatly honoured by its acquisition. Meanwhile, just over a century later, his donation of those 18 works to the V&A, made as war tore Europe apart, remains the greatest gift to the museum by a living artist.