Found, The Foundling Museum, London (until 4 September)

One of my favourite museums, the Foundling builds on its early pioneering of artist collaborations with a dynamic and imaginative programme of exhibitions and events. All of which, one way or another, tie into the Foundling Hospital’s history of caring for generations of abandoned babies. It was Hogarth and Handel’s 18th-century fundraising that helped the Foundling to become the first children’s charity. Now, integrated amongst the museum’s often heartrending exhibits, this wonderful show curated by Cornelia Parker invites more than 60 artists working across a range of disciplines—from Rachel Whiteread and Antony Gormley to Brian Eno, Marina Warner and Jarvis Cocker—to respond to the theme of “found”.

Like all great ideas, Found is brilliantly simple and yields great riches. Look out for Rose Wylie’s cardboard box, bearing the portrait of the rescue cat in which it arrived; Ron Arad’s poignant string of pawn shop tickets; and Richard Deacon’s readymade sculptural tribute to his late friend, Juan Muñoz.

Liverpool Biennial, various venues, Liverpool (until 16 October)

City-wide biennials are always sprawling, confusing beasts. But this year’s Liverpool Biennial seems almost perversely multifarious and multi-thematic. I’m not sure it was such a great idea to hand it over to an 11-strong “curatorial faculty”, especially when what they have come up with is a gnomically-described “story narrated in several episodes.” These are comprised of the somewhat random line-up of Ancient Greece, Chinatown, Children’s Episode, Monuments from the Future, Software and Flashback. Works riff across this broad thematic terrain as well as the geographically scattered city: from a disused brewery, a boarded-up street and a derelict cinema, to a covered reservoir, a Chinese restaurant and three of the city’s double-decker buses.

It is back to the future with fragments of Greek statuary collected by 19th-century industrialist Henry Blundell that are arranged in Tate Liverpool on shiny pink prosthetic structures designed by the Belgian artist Koenraad Dedobbeleer. Their often clumsy restoration assumes a more ominous resonance in the face of a film depicting news footage of recent Isil artefact-smashing. The film is made all the more grotesque by being overlaid with watercolour animation, all courtesy of the Iranian artists Ramin and Rokni Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian. This trio are a ubiquitous Liverpool presence, with many of their exuberantly assembled sculptural works also in the cavernous Cains Brewery and Open Eye Gallery. But the film is by far their best work.

Another pervasive presence is Betty Woodman, who is here best represented by a wall-mounted fountain of turquoise and bronze Egyptian-style reliefs. These are arrayed along one side of the very grand, 1930s Art Deco ventilation shaft building at George’s Dock.

I was sorry to miss Marvin Gaye Chetwynd’s Dogsy Ma Bone performance. But her ebullient collaborative presence endures at Cains Brewery in a wallpapered, prop-adorned space, displaying a film of her activities with Liverpool’s under 14’s. Other works not to be missed are Mark Leckey’s film Dream English Kid 1964-1999 AD (2015), which combines internet-trawled images of comets, eclipses, gigs and the bleak terrain of Thatcher’s Liverpool; and Lara Favaretto’s immense block of granite, which stands in the middle of a boarded up Toxteth street and offers a small slit for donations. At the end of the biennial, the monument will be smashed and any money it contains will be donated to Asylum Link Merseyside, a local charity that supports refugees.

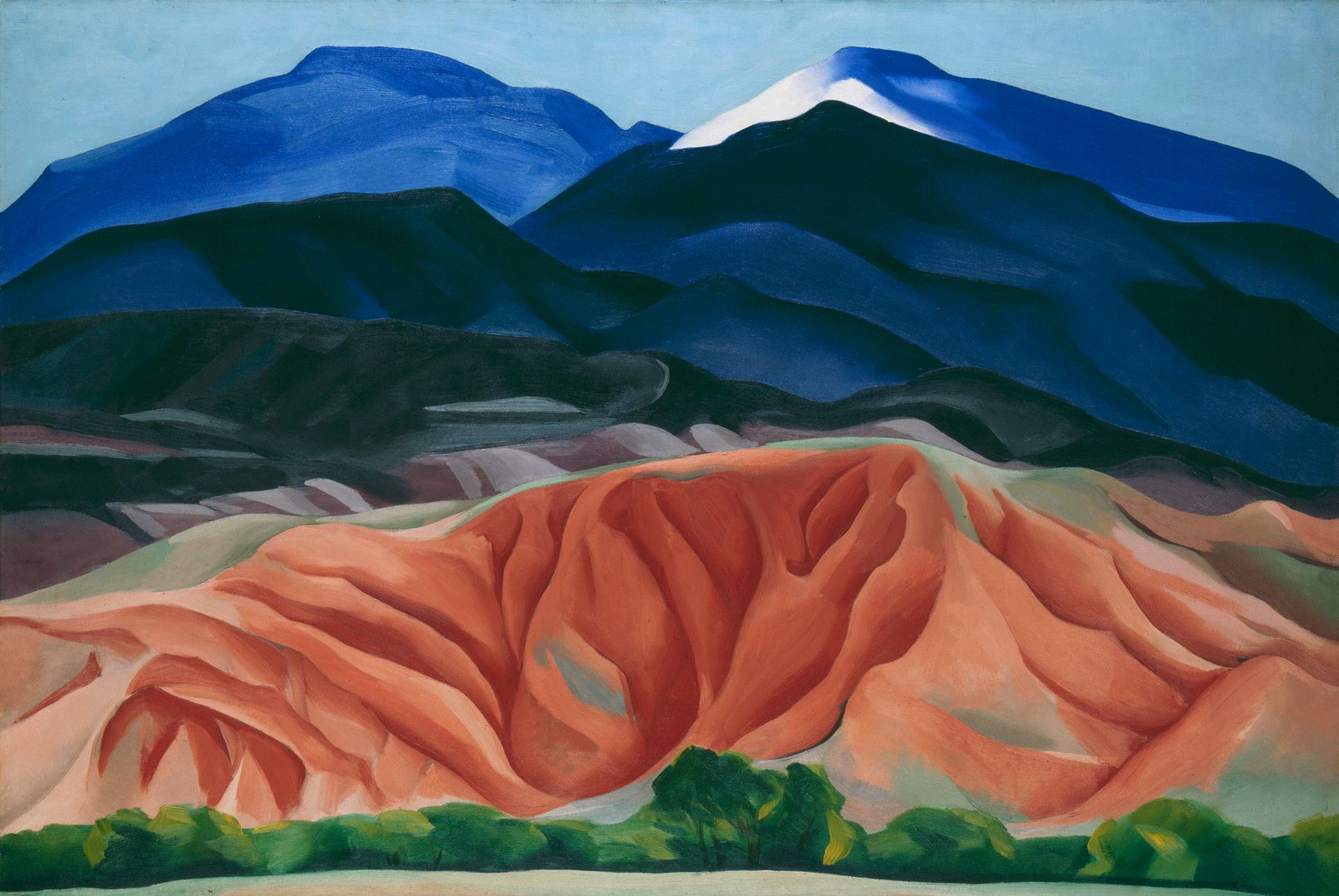

Georgia O’Keeffe, Tate Modern, London (until 30 October)

Georgia O’Keeffe’s first major UK show in more than 20 years aims to dispel what its curators consider to be the enduring clichés surrounding one of America’s best-known 20th-century artists: most notably, the sexual connotations of much of her work. It is certainly understandable why O’Keeffe also eschewed such readings—especially when they so often emphatically, and patronizingly, branded her paintings as quintessentially “female”. But there’s still no denying that many of O’Keeffe’s subjects and her handling of them—the softly-shaded labial flowers, the bodily clefts and swelling contours of her New Mexican landscapes—make it almost impossible not to view much of her work in corporal terms. Even her near-monochrome early abstracts—as well as her later bleached bone studies—have a curled, curvaceous sensuousness.

However, their evidently psycho-sexual charge is just one facet. What also emerges from his comprehensive show, is the important and constant influence of the latest developments in photography: the angles, the cropping and the enlarging of her images, as well as their smooth modelling in light. Furthermore, we are repeatedly reminded of O’Keeffe’s fascination with distilling and honing an image to its minimal essence: from her earliest charcoal and ink lines to the dark squares of her later and lesser-known “doors” series. Over more than six decades, O’Keeffe’s painterly language may have changed very little, but it was always strikingly and distinctively her own. And she wanted it viewed on her own terms.

Rita Parniczky: Weaving with Light, Contemporary Applied Arts, London (until 30 July)

Every year, the Perrier-Jouët Arts Salon—of which, full disclosure, I am a member—awards a prize to an emerging maker from the British craft sector whose work seems to provide the most interesting contemporary expression of the Art Nouveau spirit. This year’s clear winner was Rita Parniczky, whose hand-woven creations are made on a Leclerc loom from the clear plastic monofilament generally used for fishing lines. They do not easily conform to any conventional category, being part textile, part sculpture and part drawing in air. True to the original ethos of Art Nouveau, these shimmering, magical presences manage to be both organic and radical, carrying multiple resonances ranging from plant skeletons, human veins, insect wings, Gothic tracery and Islamic patterning. But at the same time they are utterly original and speak with a distinctive and highly unusual voice. A worthy winner.

Superwoman: Work, Build and Don’t Whine, Grad, London (until 17 September)

One of the all-time best exhibition titles—taken from a sternly propagandist Stalinist poster of 1930—aptly sets the tone for this fascinating exhibition. The show explores the shifting roles, and presentation, of the Soviet woman in state propaganda, from the October Revolution of 1917 through to the end of perestroika in 1991. Films, posters, works of art, ceramics, photographs and ephemera trace the crucial role played by women in the creation of the new Soviet society, beginning with the female worker’s instigation of the first revolution and their early achievement of rights: Russia was the first major power to grant women the vote, to legalise abortion and to give generous maternity leave. All of which expanded their role from citizens, mothers and full-time workers into soldiers, scientists, athletes, dancers, cosmonauts—and more.

But for many the reality soon became not quite so utopian, as under Stalin the focus shifted to industrialisation and women’s rights became increasingly marginalised. Abortion was again outlawed and the status of the mother elevated to heroic heights. Contrary to the official view, this dual role of Soviet Madonna and athletic comrade became increasingly incompatible, and the chasm between liberation and emancipation ever wider—a dichotomy that remains an issue for women beyond Russia. As many of us are all too aware, the notion of “superwoman” can be a very poisoned chalice.