An Amsterdam exhibition on Vincent van Gogh’s medical problems will include the revolver which he used to kill himself in 1890. Teio Meedendorp, a researcher at the Van Gogh Museum, believes it is highly probable that the corroded Lefaucheux revolver found in a field was the suicide weapon.

Although the pocket revolver was unearthed by a farmer in around 1960, the facts were only revealed four years ago, in a little-publicised booklet by the researcher Alain Rohan. The unidentified owner of the gun has now lent it to the exhibition, On the Verge of Insanity: Van Gogh and his Illness, which opens on Friday (15 July-25 September).

Meedendorp cites several reasons for believing the weapon was the one used by Van Gogh. It was discovered behind the château of Auvers-sur-Oise, where the artist is said to have shot himself. Experts believe that its corroded condition suggests it had lain buried for over 50 years, making it pre-1910. The gun had been in production until 1893. Tellingly, the trigger had corroded in the unlocked position, which means it was probably fired just before it being lost or abandoned.

Identifying the gun helps explain why Van Gogh was not immediately killed after the shooting. The Lefaucheux revolver has limited firepower, explaining why the bullet ricocheted off his ribs and became embedded in his chest, rather than going through his heart. On 29 July 1890, two days after the shooting, the artist died of his wound.

The ear

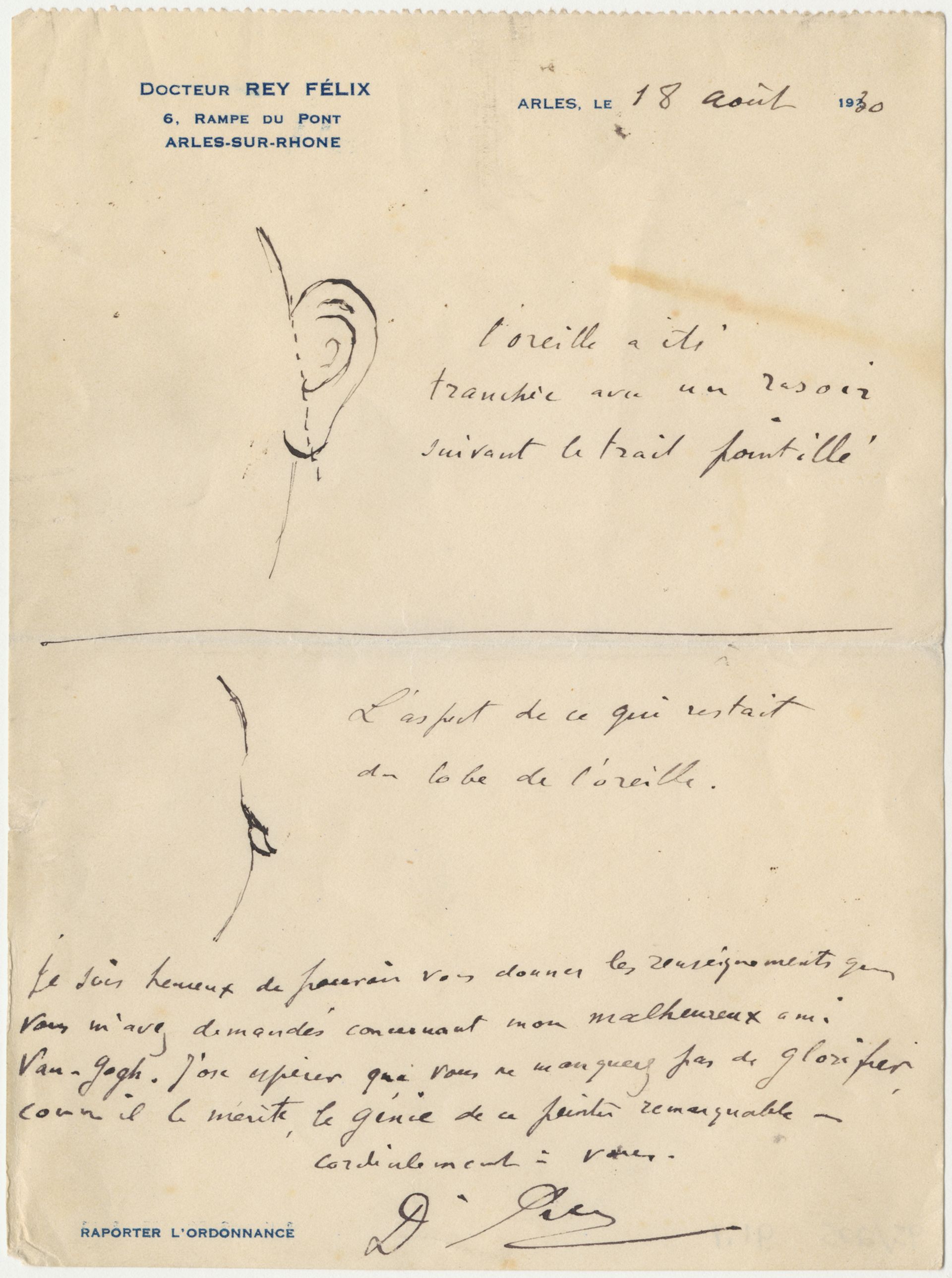

The exhibition also reveals new evidence discovered by the writer Bernadette Murphy, as revealed in her book Van Gogh’s Ear: The True Story (Chatto & Windus). Murphy found a note and diagram from Dr Félix Rey, who had treated Van Gogh in Arles after he had mutilated his ear. This note was written on 18 August 1930 for the American novelist Irving Stone, author of Lust for Life (the document has been lent to the Amsterdam museum by the Bancroft Library at the University of California).

Rey’s diagram shows that virtually the entire ear was cut off, with a caption stating it showed “what remained of the lobe”. However, another document in the exhibition tells a slightly different story. Gustave Coquiot, a Van Gogh specialist, wrote after meeting Rey on 4 May 1922 that the doctor had told him the ear had been removed “leaving only the tragus” (part of the central area of the outer ear).

The evidence of exactly what was left of Van Gogh’s ear is therefore unclear, but Rey clearly believed that most of it had been lost. This suggests that Van Gogh mutilated himself with ruthless determination.

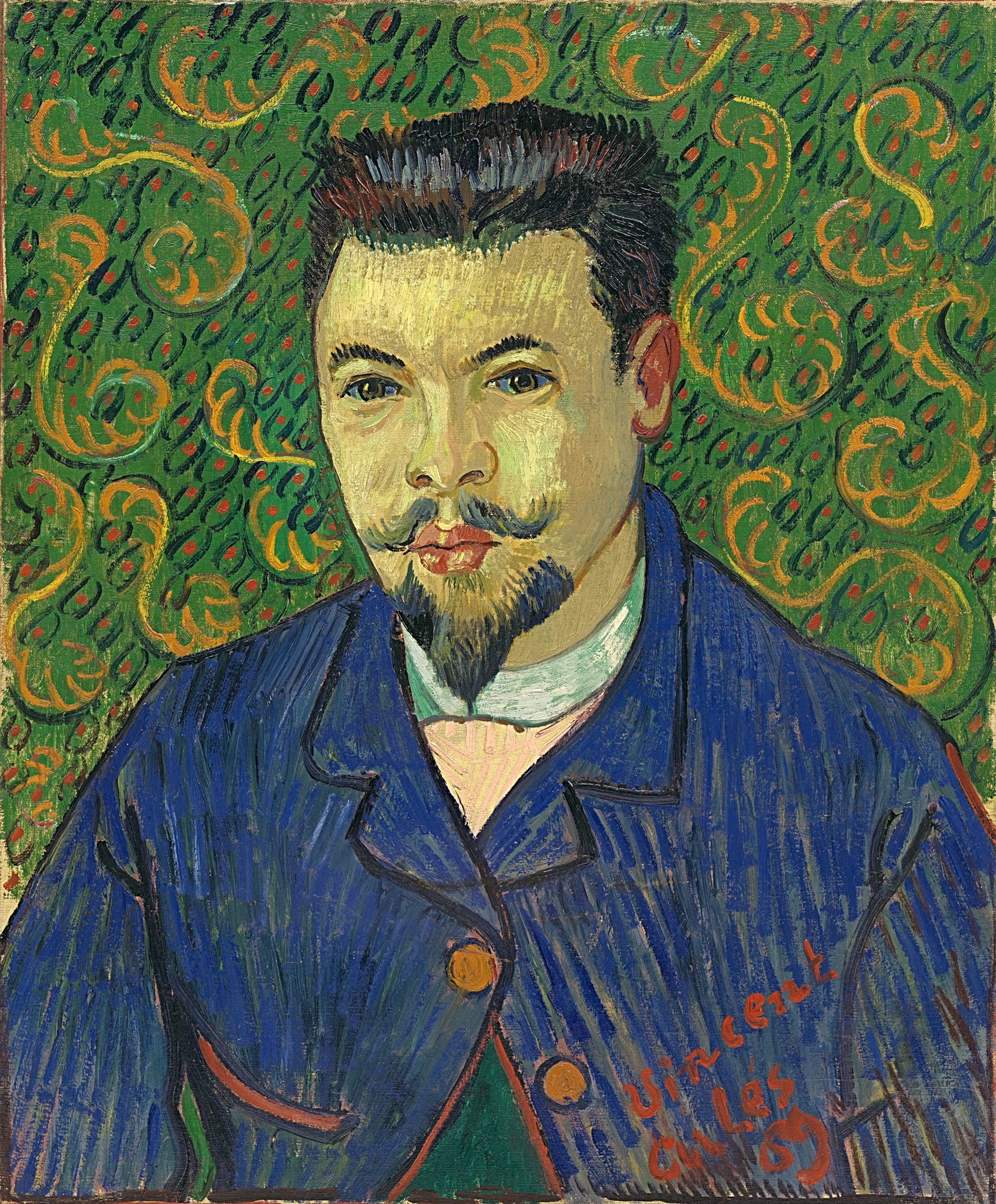

The exhibition presents key documents from the municipal archive of Arles, including the 1889 petition by local residents asking Van Gogh to be required to leave his home, the Yellow House. This petition has never been displayed before. Also included in the show are 25 paintings and drawings from the last year or so of the artist’s life. The star loan is the Portrait of Dr Rey from Moscow’s Pushkin Museum, which is being shown for the first time in Amsterdam.

Nienke Bakker, a curator of the exhibition, stresses that Van Gogh’s art should “not be viewed as a product of his illness, but rather he painted in spite of his condition”. The show proposes a number of possible medical diagnoses, although it does not reach a conclusion. Medical experts will discuss the diagnoses at a symposium in Amsterdam on 14-15 September.

Murphy’s book Murphy’s major contribution to Van Gogh scholarship has been her meticulous research in the archives of Arles, where Van Gogh lived from March 1888 until he retreated to the asylum in St-Rémy de Provence fifteen months later. Over many years she built up a database of the citizens of Arles, uncovering links between the people whom Van Gogh encountered.

This has enabled her to name two of the previously unidentified sitters in Van Gogh’s portraits. She says the young girl in an Arles portrait was probably 12-year-old Thérèse Catherine Mistral, who lived five minutes’ walk from the Yellow House. Murphy identifies the peasant painted twice by Van Gogh as François Casimir Escalier, who died a few months after the artist’s departure (Van Gogh named him as Patience, but Murphy believes that this was a nickname, describing his character).

Most importantly, Murphy says she has identified the young woman at the brothel to whom Van Gogh presented his ear, who has long been known to have been named Gabrielle. Murphy has traced her descendants, but has not revealed the surname, at their request. She says that Gabrielle was not a prostitute—but worked as a maid in the brothel.

• Martin Bailey is a Van Gogh specialist and author of The Sunflowers are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh’s Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln, 2013)