The ninth edition of the Liverpool Biennial (until 16 October) invites international artists to examine the city’s past, present and future. While the stories they spin are not all to be trusted, the works that linger in the mind are those that engage closest with the local context.

In some cases, fiction proves more seductive than reality. The Iranian brothers Ramin and Rokni Haerizadeh and their collaborator Hesam Rahmanian, whose works run through three of the main exhibitions, overlay spliced footage of Isil iconoclasm with their own watercolour animations in Big Rock Candy Mountain (2015). The video, part of Tate Liverpool’s show mixing contemporary art with National Museums Liverpool’s 18th-century collection of classical sculpture, converts militants into bikini-wearing dancers, long-beaked birds and gaping fish, seemingly neutralising their destructive acts.

The glossy films of Fabien Giraud and Raphaël Siboni in the spectacular, ruined ABC Cinema, which closed in 1998, and Lucy Beech at Fact (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology) promise cinematic escapism. Both dystopian narratives—the first an apocalyptic vision of 1920s factory workers with the look of a 1980s music video, the second an uneasy encounter with a cult-like therapy group—seem to make more sense in light of the fact that the University of Liverpool houses one of the largest science fiction libraries in the world.

The biennial feels strongest when the commissioned artists work directly with the city’s people and places. One of the highlights of the opening weekend was Marvin Gaye Chetwynd’s Dogsy Ma Bone, a joyful Scouse musical inspired by Betty Boop and Bertolt Brecht with a cast of local children in handmade animal costumes. A film of the production, shot on the streets of Liverpool, will be screened daily at the Cains Brewery venue.

A more sober collaboration with and for children comes in the form of Koki Tanaka’s exhibition at Open Eye Gallery, which revisits the 1985 march by 10,000 Liverpudlian school students against the Youth Training Scheme, Margaret Thatcher’s controversial government initiative intended to reduce mass unemployment among young people. In the wake of the UK’s Brexit referendum, the project asks whether the new generation of digital natives can rekindle the same spirit of political protest.

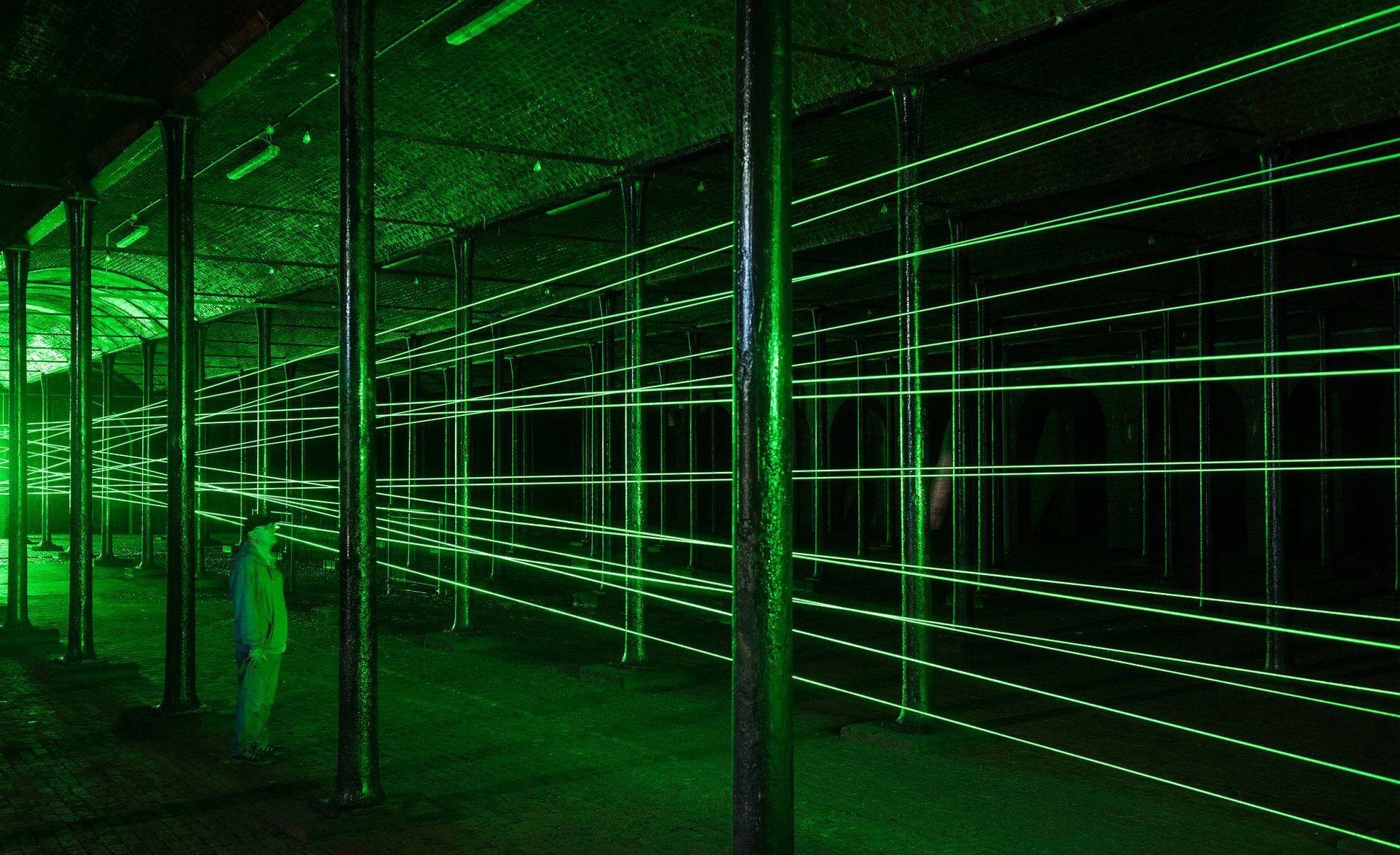

While the original participants seem doubtful in Tanaka’s interviews, there is cause for optimism at the longer-term transformation of Liverpool’s urban fabric. Beyond the city centre, the biennial has pushed out to the Toxteth community, where riots erupted between residents and police in 1981. The temporary interventions Portal, a web of green laser beams created inside the former Toxteth Reservoir by Rita McBride, and Momentary Monument, Lara Favaretto’s slab of granite on a boarded-up street, are a walk away from Granby Four Streets, the Turner Prize-winning project by the architecture collective Assemble to regenerate the area’s derelict terraced houses.

Meanwhile, Liverpool City Council, one of the biennial’s main funders, has granted planning permission to a ten-year redevelopment plan for the Cains Brewery site. After the biennial runs its 14-week course, the complex of disused warehouses is due to be refurbished as artists’ studios and gallery spaces.

• Liverpool Biennial, various venues, until 16 October