Frances Morris, Tate Modern’s new director, has finally begun to work in the galleries of her institution’s extension, ten years on from the Tate’s first announcement about the building. “I am incredibly relieved and very excited indeed,” she says.

Click here for a photo tour inside Tate Modern's new extension

Her enthusiasm is understandable: with 75% of the works on display acquired since 2000, much of the art she is now installing was bought during her time as director of the Tate’s international collection.

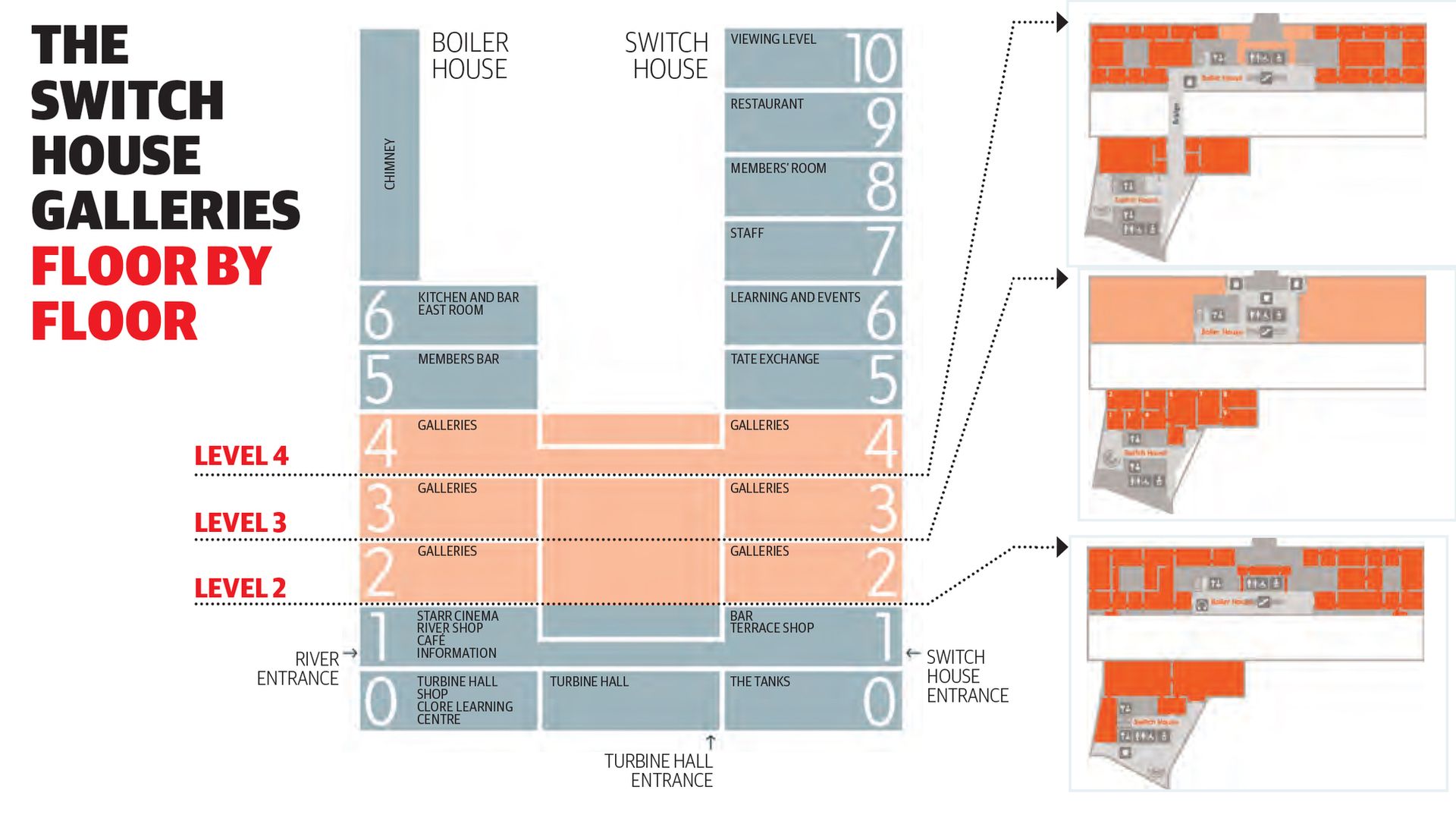

There is a simple division between the new building, which the Tate calls the Switch House, and the galleries built in 2000, known as the Boiler House (the Turbine Hall, of course, completes Tate Modern’s industrial triumvirate). In the Boiler House, as has been the case since 2000, the art covers the years between 1900 and 2016. But the Switch House displays begin in 1960.

Morris explains that the subterranean Tanks spaces, for performance, film and installation, have been “one of the guiding principles in collecting in the last ten years”. She wanted displays that reflected “participatory art or the debate around art and audiences”, and felt that 1960 “was the point where you can articulate that with the greatest authority”. That decade witnessed “that moment when high Modernism erupted”, Morris argues, with huge shifts, socially, politically—and artistically. “If there is a pivotal moment to make a switch of tempo, it is in the 1960s.”

The Tate’s much-touted broader geographic spread (see the Nicholas Serota interview) will be reflected in displays that explore familiar artistic developments from novel viewpoints. The collection has been built “around moments in time”, Morris says, “where there’s clear evidence of strong transnational connections”. For instance, one display looks at pure abstraction from the point of view of São Paulo rather than a European centre, focusing on the artists who regularly showed in the Brazilian city’s biennial alongside Brazil-based artists.

The new hang continues to resist chronology, as Tate Modern has since 2000. “Our displays are full of history,” Morris says. “They may not be organised according to strict chronological ‘this happened, then that happened, then that happened’ thinking, but they really are about why things happened in relation to each other, across time and across the world.”

But while the displays strategy is consistent with Tate Modern’s first phase, the new galleries depart from the existing architecture. “Broadly speaking, on every floor the galleries are very different, Morris says. “What is nice about the Switch House is that we’ve retained that rawness in the Tanks, which is genuinely industrial. There are not many museums that have been able to resist putting in the kind of infrastructure and conditions that take away from that.” The building “is so fantastic”, she says. “What we can do with it takes us to a different place.”

LEVEL FOUR: WINDOWS ON TO THE LANDSCAPE Frances Morris: “On the top gallery floor, there are two huge, beautiful expansive spaces, one of which is top-daylit. They both have windows on to the landscape. We can do what we like with them—we can put in walls or we can just have big open spaces. And they are bigger as individual spaces than any of the individual spaces we have in the Boiler House. They have lovely proportions.”

LEVEL THREE: A LABYRINTH OF ROOMS Frances Morris: “Level three is slightly lower ceilinged and is divided into rooms. I say rooms, because they have the intimacy of rooms, but they don’t have the boxiness of the little rooms of the Boiler House. And the reason for that is that they have much wider entrances, so they’re not even doorways. It’s like a labyrinth of spaces. They’re generous—you can see from space to space, you never feel confined in a room—but it will mean that you can articulate a series of works that need a bit of containment, whether they are smaller scale, groups of photographs or installations.”

LEVEL TWO: ONE HUGE, UNBROKEN SPACE Frances Morris: “Although we’ve put in a dividing wall, it is architecturally one huge, unbroken space—more or less the same size as a wing in the Boiler House, without an internal structural wall. We’ve never had that at Tate Modern. Actually, I’ve never had that in my life. So the possibilities, either for dividing it up in the way that you want, or just working with an empty space, are very exciting. And that’s the space that will become the exhibition space in 2018.”