“In my life and work, I choose to celebrate the beautiful. I’ve seen enough horror, so why put it in films or on paper?” asks the nonagenarian artist Jonas Mekas, also known as the “godfather of avant-garde cinema”. “Others concentrate on the dark, depressing aspects of humanity—and there’s a lot to document because humanity today is pretty horrible. But there are still fragments of paradise around us and we have to keep them alive. That is my responsibility. That is simply what I do.”

Born on Christmas Day in Lithuania, amid the turmoil of inter-war Europe, Mekas has led an extraordinary life. “It’s a complicated story,” he says, with a shrug that is almost audible. After joining the resistance during the Second World War, he and his brother Adolfas had to flee their homeland but were caught by the Nazis and taken to a forced labour camp in Germany. After the war, they spent “four or five years in a displaced persons camp”, says Mekas, describing it as a “very similar situation to today”.

“There wasn’t much to do” in the camps, so Mekas used his camera to “record life”, capturing the melancholy of displacement as well as random moments of joy. A selection of the photographs is on show at Art Basel with James Fuentes, priced at $10,000 each in an edition of five. “They are a unique record, because not much exists from those camps,” Mekas says. “It’s a glimpse into the realities of that period.”

A 1948 photo by Jonas Mekas of refugees at Kassel railway station, Germany, waiting to be transported to another displaced persons camp. His work will be on at Art Basel with James Fuentes

In 1949, the International Refugee Organization brought the brothers to New York, where they settled in Brooklyn and quickly became enmeshed in the avant-garde film movement: “We got involved immediately and totally. It’s a magnificent obsession,” says Mekas, who will be in conversation this week with Bernd Scherer, the director of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin.

A pivotal figure in the downtown arts scene, Mekas was a catalyst for other artists, including Andy Warhol, whom he inspired to make films (Mekas operated the camera for Empire (1964), Warhol’s eight-hour meditation on the Empire State Building). And he was on first-name terms with the former First Lady Jackie Kennedy, who asked him to tutor her children in film and photography.

“I consider it all very normal—it was part of one’s life,” says Mekas, who is a prolific poet and writer (his Lithuanian poetry is now part of that country’s classic literature). “Whatever I did, I did it because nobody else was doing it,” he says. “Nobody was writing about independent cinema, so I had to start a movie journal. Nobody was screening our films, so I had to start the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque. There was no film magazine, so I had to do that. It was always from necessity because otherwise why do it?”

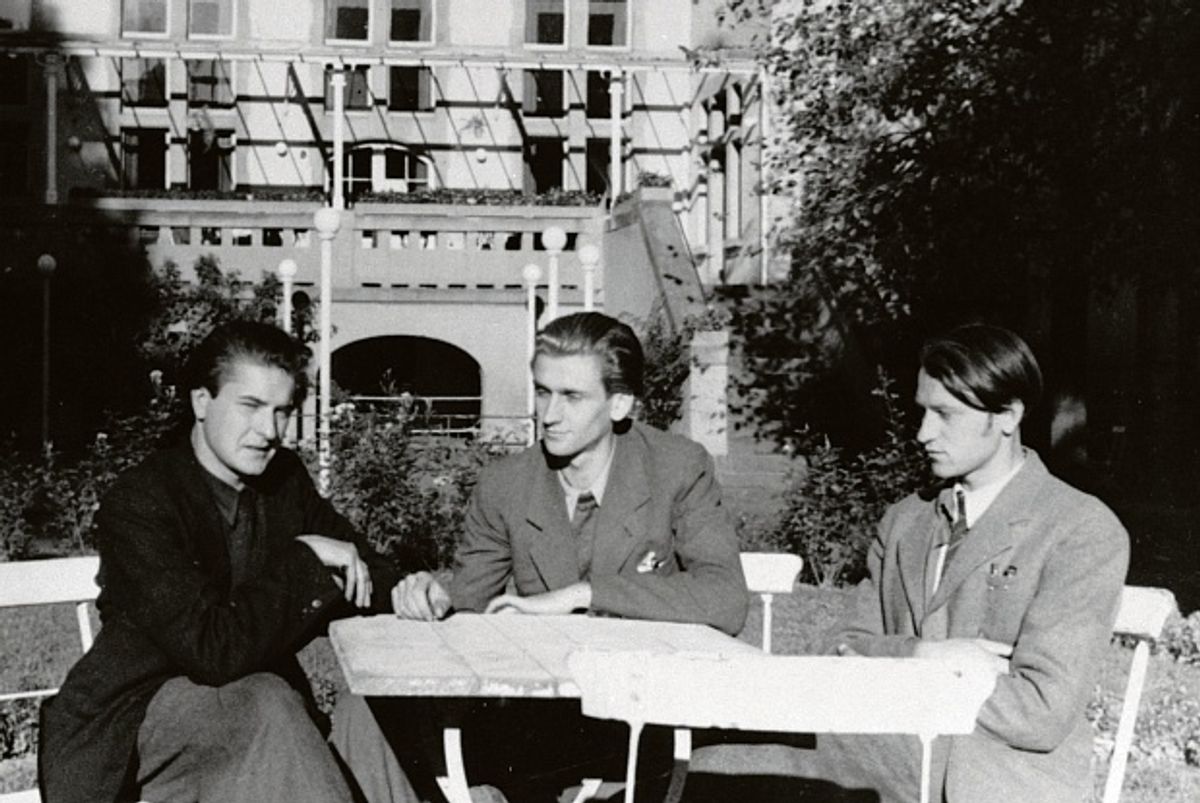

Mekas's brother at the Kassel Mattenberg displaced persons camp in 1948. Photo: Jonas Mekas

Without Mekas, “experimental film is unthinkable”, says Stuart Comer, the chief curator of media and performance art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. A pioneer of the diary film, Mekas documented his return to his homeland 27 years after leaving in Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1971-72), part of Art Basel’s film programme. Officials from the Soviet Union, which annexed Lithuania during the war, tried to make Mekas destroy the work because, he says, “I was not showing the progress or achievements of the Soviet Union. I was totally somewhere else—I was in the Lithuania of my childhood.”

Throughout his career, Mekas has been quick to adopt new media. “Only with technology can you access the certain sensibilities and realities of your time. Perceptions of reality change with technology,” he says. “Everything in the 19th century was slow; now everything is fast and multi-layered. New digital technology permits you to go into any situation and not force anything on that reality, but very casually, to capture its completeness.”

Jonas Mekas, Kassel/Mattenberg, the camp school/movie house/church... (1948)

He says distribution and dissemination today is essential because, “as bad as the world is, it’s more like one piece than [it was] in the 1960s because of technologies, which I believe will help to unite it. Of course, it’s like a knife; you can use it to cut bread and serve family and friends, or to kill.”

Comer credits Mekas with building “a magical community at the crossroads of avant-garde film, Fluxus, Pop and the underground that continues to be a life force for many young artists today.” This spirit of collaboration is driven by a fundamental optimism: “I trust and follow those who lived before me—the poets, singers, artists, musicians, scientists and saints who did everything so that humanity would become more beautiful,” Mekas says. “Every moment I am not dead I am thinking about how not to betray them. I have to help continue their work.”

Jonas Mekas’s plea to Hollywood: help expand New York film archive

Mekas is fundraising for a $6m expansion of the Anthology Film Archives, which he founded in New York in 1969. “I want to share and preserve for those who will come after us those films I enjoyed,” he says. He plans to build a library to document paper materials (the film library already exists) chronicling the history of cinema over the past 100 years on top of the existing building, as well as a café.

“Preserving the anthology is like preserving the New York we all love,” says James Fuentes, whose gallery represents Mekas. The artist has secured $3m towards the renovation, and various artists, including Cindy Sherman, Elizabeth Peyton, Richard Serra and Matthew Barney, have pledged to contribute works to an auction in New York this autumn to help raise funds for the project.

Mekas is also calling on the film community to help. “During the past 30 years, we have shown many first works by film-makers who later became successful in Hollywood, and I feel like they should help me build this library,” he says. “But somehow my efforts to reach them always end up in zero. I do not understand—they should not stay on the outside watching how I struggle to build it. Sometimes it is frustrating, but I consider that it is like a cathedral of cinema and I am determined,” he says. “I know it will one day be finished because many cathedrals took a long time to build.”

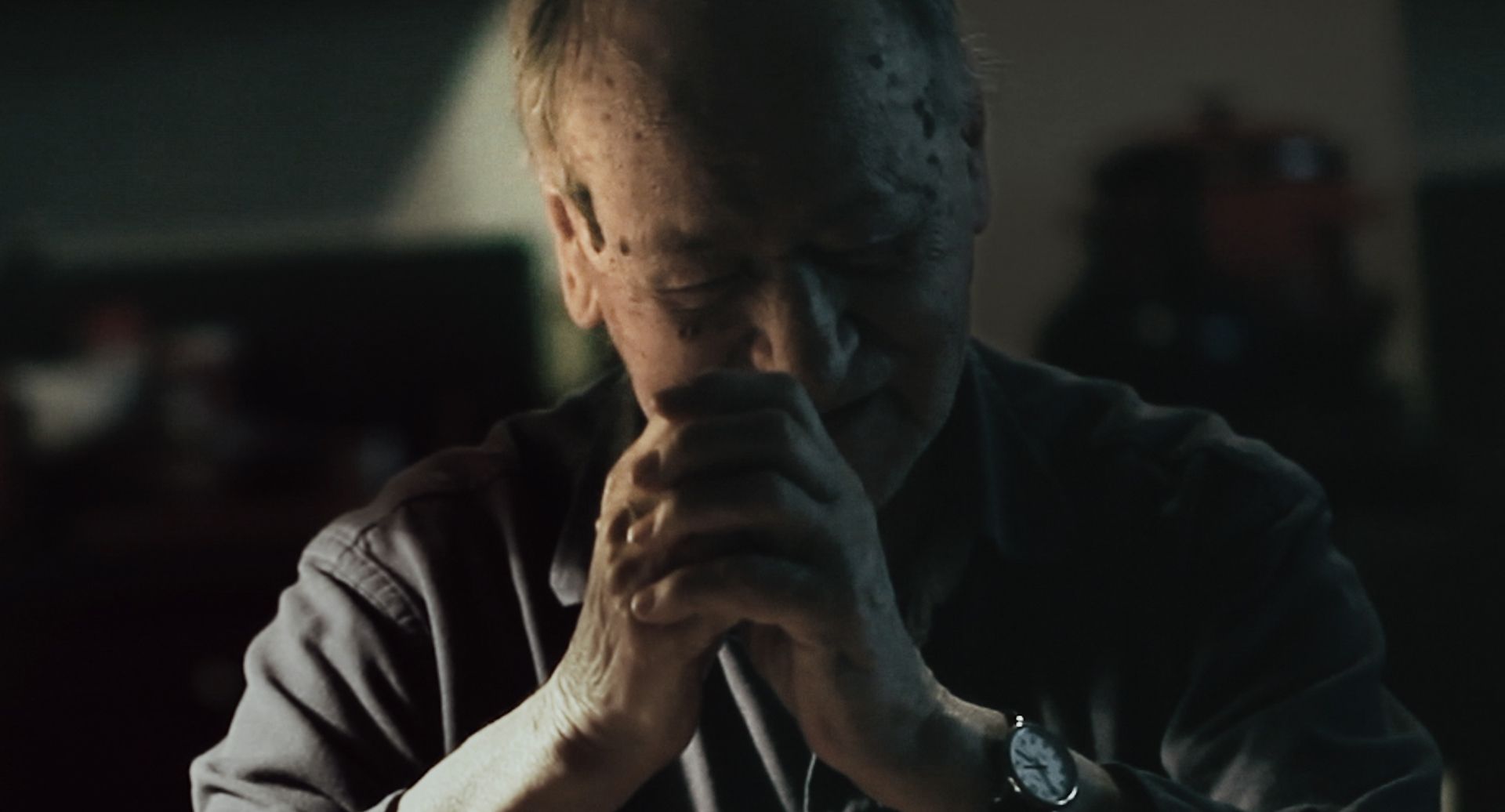

Jonas Mekas reads from his 1991 memoir in I Had Nowhere to Go, directed by Douglas Gordon

Timeline

1922: Born in the farming village of Semeniškiai, Lithuania

1944: He and his brother Adolfas were taken by the Nazis to a forced labour camp in Elmshorn, Germany

1949: The International Refugee Organization takes the Mekas brothers to New York. They settle in Williamsburg, Brooklyn

1954: The brothers launch the influential magazine, Film Culture

1958: He becomes the first film critic of the Village Voice, focusing on non-commercial cinema (an anthology of his now-legendary Movie Journal column has recently been reissued by Columbia University Press)

1962: Founds the Film-Makers’ Cooperative

1964: His film, The Brig, is awarded the Grand Prize at the Venice Film Festival

1964: Launches the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque, which expands to become the Anthology Film Archives, housing the most extensive library of experimental cinema in the world

2007: He completes a series of 365 short films released on the internet, one per day

• Film: Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1971-72), Jonas Mekas, Thursday 16 June, 8pm, Stadtkino Basel

• Artist talk: Jonas Mekas in conversation with Bernd Scherer, Saturday 18 June, 2pm, Auditorium, Hall 1