Once the Tate had settled on the inactive Bankside Power Station as the home of what was then to be the Tate Gallery of Modern Art in 1994, a competition was launched to find the architects to turn this hulking building into a museum. From 150 submissions, a shortlist of 13 architects was invited to prepare schemes, and this was further whittled down to six finalists who would submit detailed proposals.

In 1994, Herzog & de Meuron were not the “starchitects” they are today, and had the Tate’s panel been less willing to put its faith in a relatively young practice, or been more inclined to favour British architects, for instance, we might have had a very different museum.

It was a tricky brief, as Michael Craig-Martin, then a Tate trustee and on the competition panel, recalls. “Bankside Power Station wasn’t really a building, it was a shoebox. It was four exterior walls with a big machine in it, and when you took out the big machine all you had was a giant empty box,” he says. “I think what Herzog and de Meuron did was the most brilliant move—having the Turbine Hall as the centre of the museum rather than the periphery, and making the entrance on the lower level, which made the whole thing grander. It is extraordinarily clever and built for peanuts, really, given its size and importance.”

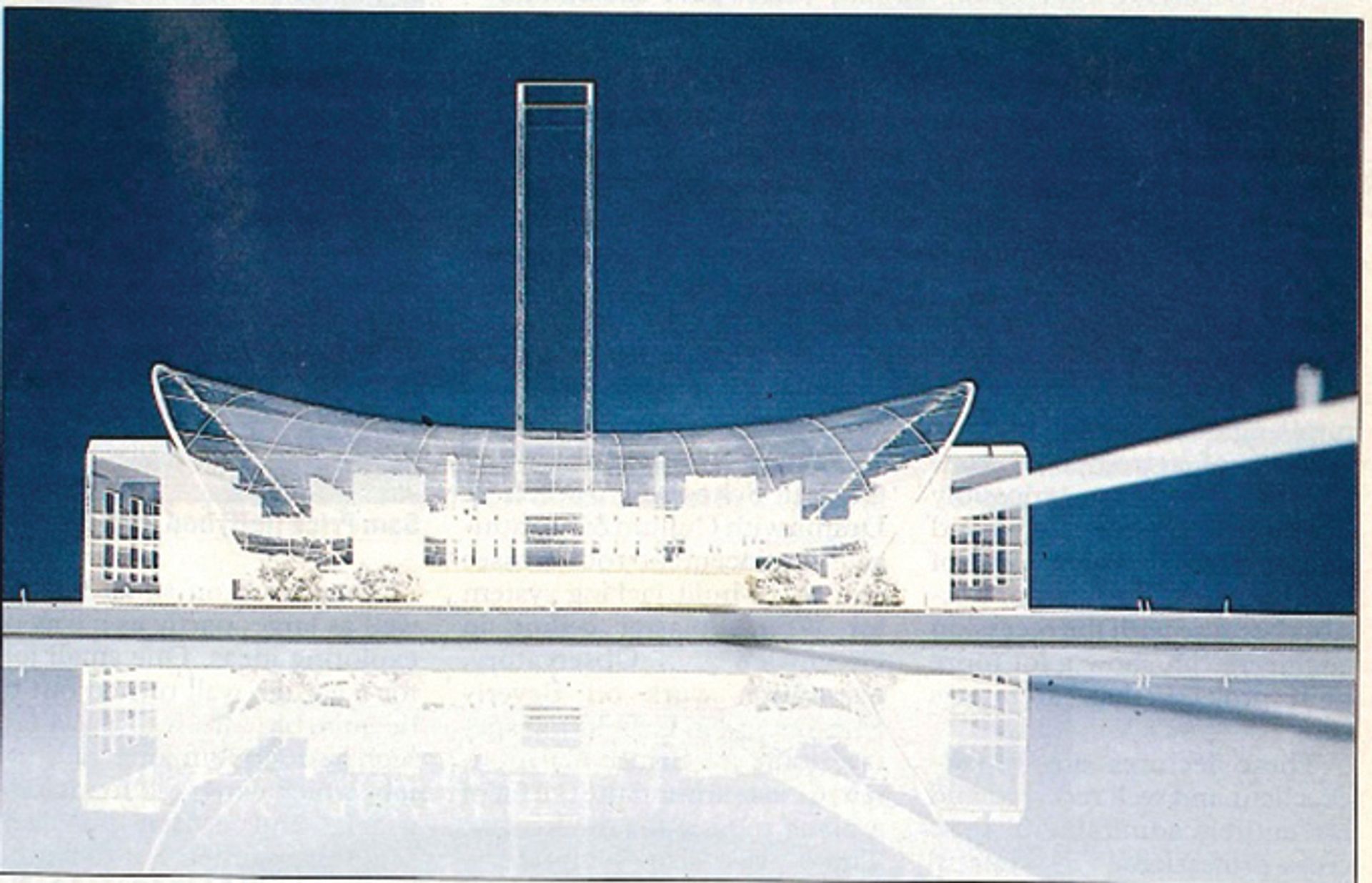

Among those to be jettisoned at shortlist level were a host of British practices, including Alsop & Störmer, Future Systems, Michael Hopkins & Partners, and Nicholas Grimshaw & Partners. Future Systems’s design was clearly formally consistent with their media centre at Lord’s Cricket Ground, with a spacey glass canopy—they would also have removed the Turbine Hall, now Tate Modern’s most famous space.

The list of finalists must surely be among the most prestigious groups ever gathered for a competition: Rafael Moneo, David Chipperfield, Herzog & de Meuron, Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, Renzo Piano Building Workshop and Rem Koolhaas/OMA. Whoever won, London was promised world-class international architecture.

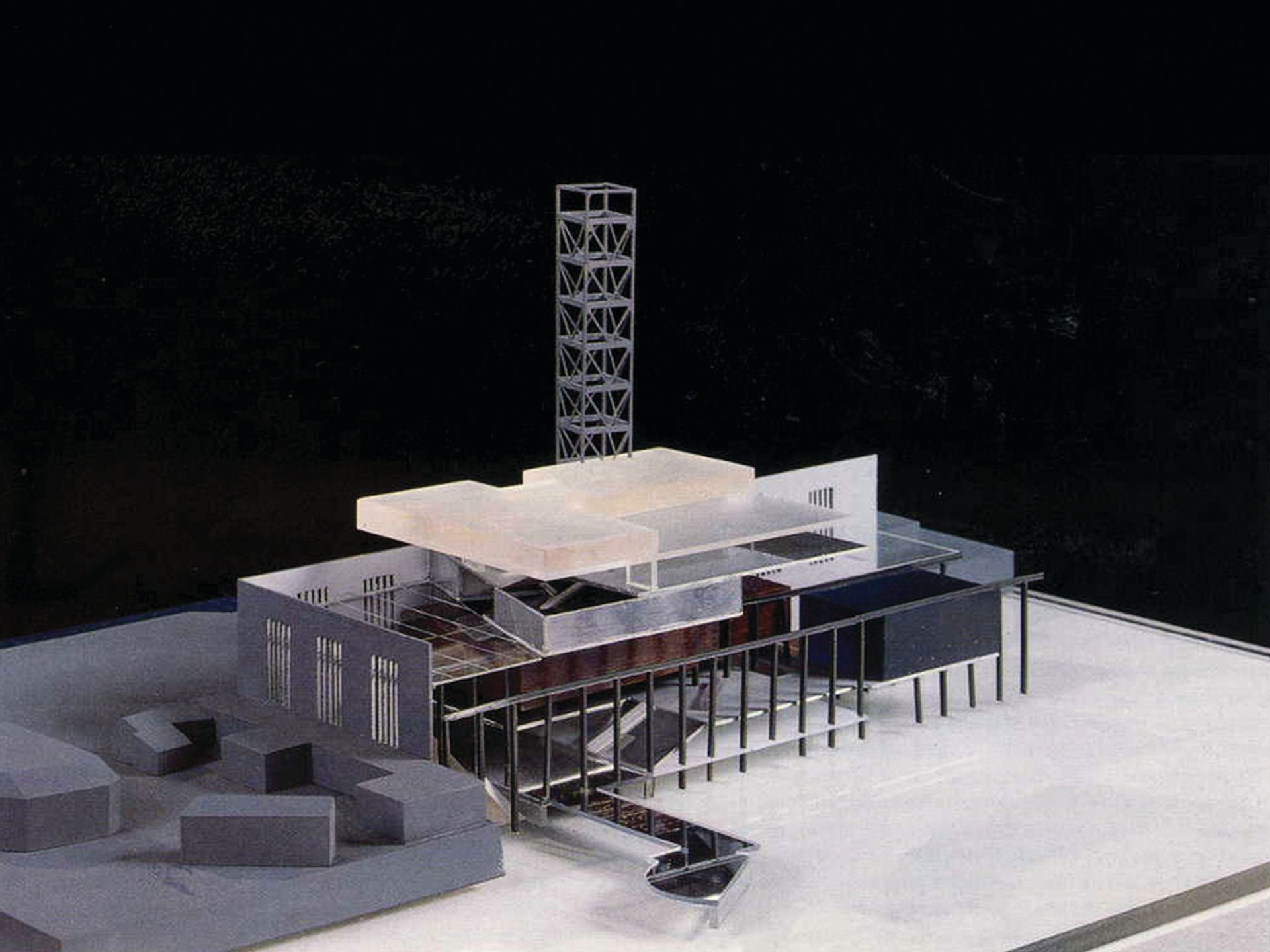

The proposals varied greatly, but much interest focused on the stand-out element of Bankside: its chimney. Koolhaas would have stripped it of its bricks and turned it into a steel skeleton; Chipperfield did the unthinkable and proposed removing the chimney altogether.

All the architects proposed various additions to the stark geometry of Giles Gilbert Scott’s power station. But there was a clear winner during the presentations, as Craig-Martin remembers. “It was an amazing situation because some of the greatest architects in the world came in and I was part of the client,” he says. “And what was very interesting is that most great architects hated the idea that they had to build something inside a shell designed by somebody else. Most architects want the profile of the building, and the limitation was that they had to put it inside this existing building.”

A common trait emerged: “When they made their presentations, each had to make a model the same size. So each architect came in with the model and almost invariably would grab the chimney and lift the shell off. Inside would be the building that they really would have liked to have built, had it not been for the shell.

“The only architects who truly turned the building into a building itself were Herzog & de Meuron. Everybody else built something in it; they proposed turning it into a building.”

This response was partly “generational”, Craig-Martin suggests. “[Herzog & de Meuron] were not put off by the sense that they were transforming an existing building; they’d done a lot of buildings already that had involved doing that, and that is a much more contemporary practice than a traditional Modernist practice. It just seemed right for that project.”

The Tate announced Herzog & de Meuron as the architects in January 1995. Twenty-two years later, that relationship continues to thrive.

• The photograph above features the following people, numbered from the left: 1) Hiromitsu Kuwata, architect, Tadao Ando’s team, 2) Masataka Yano, architect, Tadao Ando’s team, 5) Julian Harrap, architect, specialist in the restoration of historic buildings, 6) Amanda Levete, then at Future Systems, 7) Jan Kaplický, Future Systems, 8) Ricky Burdett, architect on the judging panel, 9) Nicholas Grimshaw, shortlisted architect , 10) Shunji Ishida (in front), architect and member of Renzo Piano’s team, 13) Rick Mather, shortlisted architect, 14) Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate, 15) John Pringle, architect, then at Michael Hopkins and partners, 16) Michael Craig-Martin, artist and Tate trustee, on judging panel, 17) Mark Whitby, structural engineer , 19) Renzo Piano, shortlisted architect, 20) Jacques Herzog, winning architect, 21) Will Alsop, shortlisted architect, 22) Rem Koolhaas, shortlisted architect, 24) Claudio Silvestrin, shortlisted architect with Rolfe Judd, 26) Rolfe Judd, shortlisted architect, 27) David Chipperfield, shortlisted architect. Members of the architectural teams of Rafael Moneo and Arata Isozaki were also present but cannot be identified