In the winter of 1778, a monkey named Jack entertained distinguished English visitors to Naples by picking up a magnifying glass and “very gravely” examining the tiny figures on ancient Greek and Roman carved gems and cameos. Jack’s owner, Sir William Hamilton, the English ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples, had trained him to look at antiquities “by way of laughing at antiquarians”—as a parody of over-serious connoisseurs and collectors of ancient art.

If Jack the connoisseur failed to amuse, he had other tricks that Hamilton could show a selected few guests, who were invited to observe the monkey during his morning swim. Jack and Gaetano, Hamilton’s young Italian servant, would plunge into the sea. The naked Gaetano struggled to control the mischievous Jack; at crucial moments, Hamilton would bark orders, distracting Gaetano enough for Jack to slip free and perform his favourite stunt of yanking the boy’s testicles (“and then he always smells his fingers”, Hamilton wrote in a letter describing the entertainment).

A serious collector Hamilton’s visitors laughed at Jack’s examination of antiquities precisely because Hamilton was one of the obsessive collectors he had trained his monkey to mock. And the monkey’s fondling ancient gems is not as far removed from pulling at a servant’s testicles as it might seem. Creating links between ancient art and sexual play was a habit of Hamilton’s. Like Tiberius before him, he is an example of a collector who formed an erotic obsession with his antiquities. His surviving letters and other personal documents allow us to understand the depths of this obsession.

Jack was not the only creature Hamilton trained to show off his ancient art collection for guests—by far his greatest creation was his mistress, Emma. Emma came highly recommended. George Romney and other prominent London painters had used her as a model for years. For one of his canvases, Romney painted the then 17-year-old Emma as Circe, the ancient Greek sorceress who enchanted Odysseus.

The painter knew Emma through her lover, Charles Francis Greville. But Greville’s finances were bad and he sought a rich woman to court. The son of Hamilton’s sister, he wrote to his uncle with a novel proposal. Hamilton’s wife had died the year before, and he had mentioned in his frequent correspondence with his nephew that he was lonely in Naples without her. Hamilton had both met his nephew’s mistress and seen examples of the paintings inspired by her. Perhaps, Greville wrote, his uncle could do him the favour of taking his lovely mistress, quite compliant, off of his hands. After some hesitation, Hamilton sent enough money to pay for Emma and her mother to travel to Naples, and he permitted himself to think that everything would go smoothly: “The prospect of possessing so delightful an object under my roof soon certainly causes in me some pleasing sensations, but they are accompanied with some anxious thoughts as to the prudent management of this business; however, I will do as well as I can and hobble in and out of this pleasant scrape as decently as I can.”

Mistress and muse Nobody consulted Emma. Though she was not as compliant as Greville had promised, she eventually succumbed to the charms (or at least the necessity) of Hamilton, who had been wooing her with picnics, new clothes, and singing lessons. And art, of course. “A beautiful plant called Emma has been transplanted here from England, and at least has not lost any of its beauty,” Hamilton wrote to the botanist Sir Joseph Banks. Long before she became his mistress, Hamilton owned Emma and her beauty in paintings, sculptures in wax, clay, marble, bronze, paper silhouettes, and cut into precious stones. “The house is ful [sic] of painters painting me,” Emma reported in a letter to Greville, with whom she continued to correspond. “He as now got nine pictures of me, and 2 a painting. Marchant is cutting my head in stone, that is in cameo for a ring. There is another man modeling me in wax, and another in clay. All the artists come from Rome to study from me, that Sir William as fitted up a room, that is called the painting-room.”

But Hamilton never permitted Emma to be represented as Emma. She was always shown as someone else, usually someone from Greek or Roman antiquity: Berenice, Euphrosyne, or Iphegenia; a nymph, a muse, or a bacchante. The famed beauty, toast of London’s gentlemen, had become another element of Hamilton’s collection of antiquities.

Excavating the erotic When Emma arrived in Naples, Hamilton was already an established collector of ancient art. The latter half of the eighteenth century was an ideal time to be a connoisseur of antiquities in Naples. The royal excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum were producing a wealth of new discoveries, often with erotic themes—from attractive nudity to priapic imagery and frescoes from the walls of brothels that serve as an illustrated menu—that appealed equally to the ancient imperial Romans and the titillated viewers of the Enlightenment era. Hamilton was no exception. About the recent discovery at Pompeii of a “Venus of marble coming out of a Bath & wringing out her wet hair” he wrote to a correspondent, “What I thought most remarkable was that all her tit bits such as bubbies mons Veneris &c are double gilt & the gold very well preserved, the rest of the marble is in its natural State.”

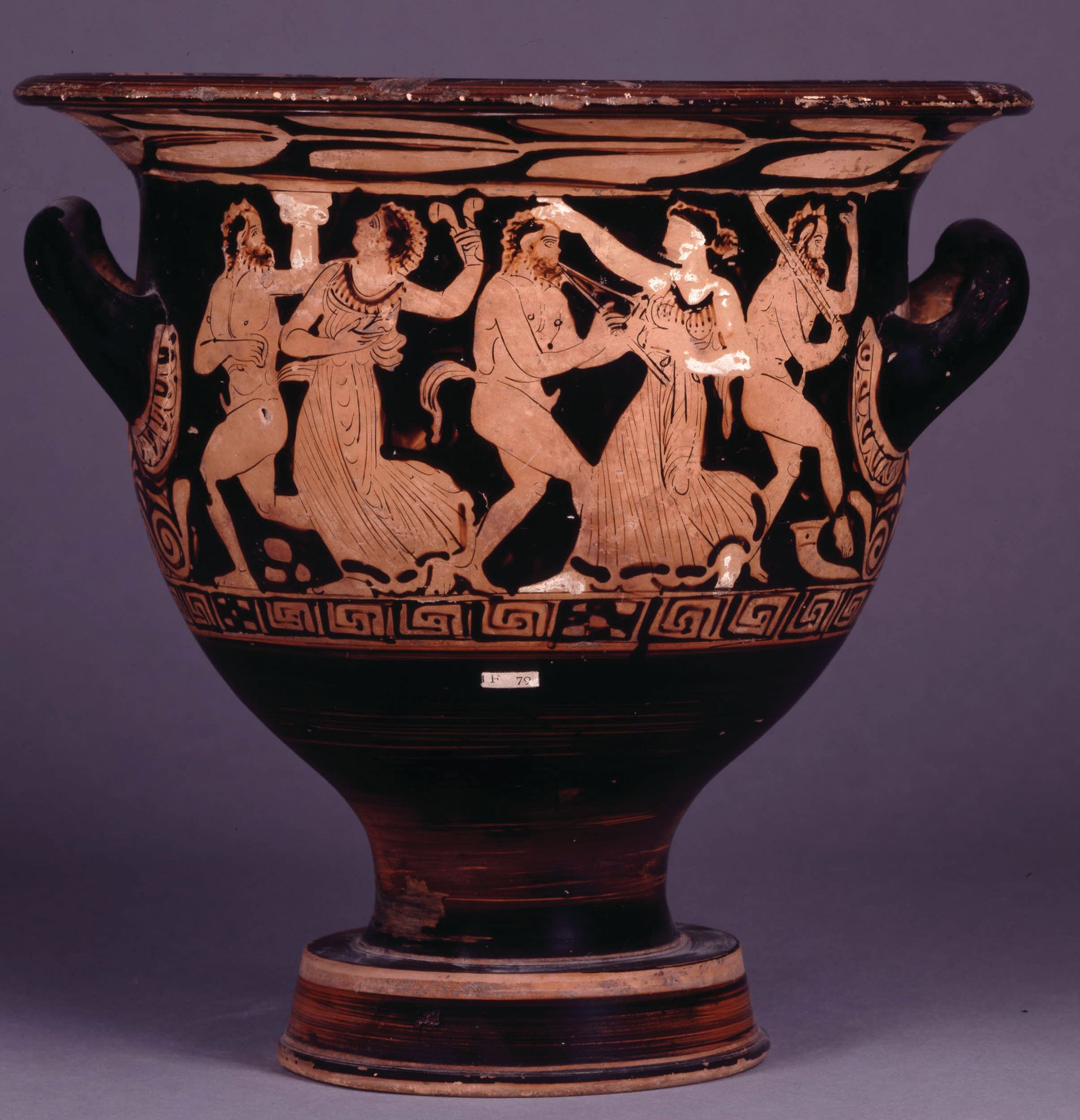

Because the discoveries from Pompeii and Herculaneum were rarely available for sale, Hamilton focused on another field: ancient Greek painted vases. These vases, produced in Greece and southern Italy in the sixth to fourth centuries BCE, were decorated with images of gods, heroes, and morals. Some showed mythological scenes and some episodes from everyday ancient life, and the decorations of most, with images of grape vines and inebriated revellers, made reference to their purpose—holding wine for ancient celebrations.

At first, Hamilton bought vases from dealers or collectors, but soon after his arrival in Naples, he sought out more direct sources. The vases survived from antiquity because the ancient inhabitants of the area surrounding Naples had buried themselves with them, holding one last drink of wine for the long road ahead. Hamilton ordered his agents to bring him word of newly discovered tombs, unearthed by peasants’ ploughs, earthquakes, or other disturbances. He even commissioned a joint portrait of himself and Emma attending the opening of a tomb.

Both he and Emma recognised the intertwined nature of his love for her and his love for his collections. He wrote to Greville about how, having arranged some of his newly acquired vases in a new apartment (a room or suite of rooms) in his house, “Emma often asks me, do you love me? But as well as your new apartment?”

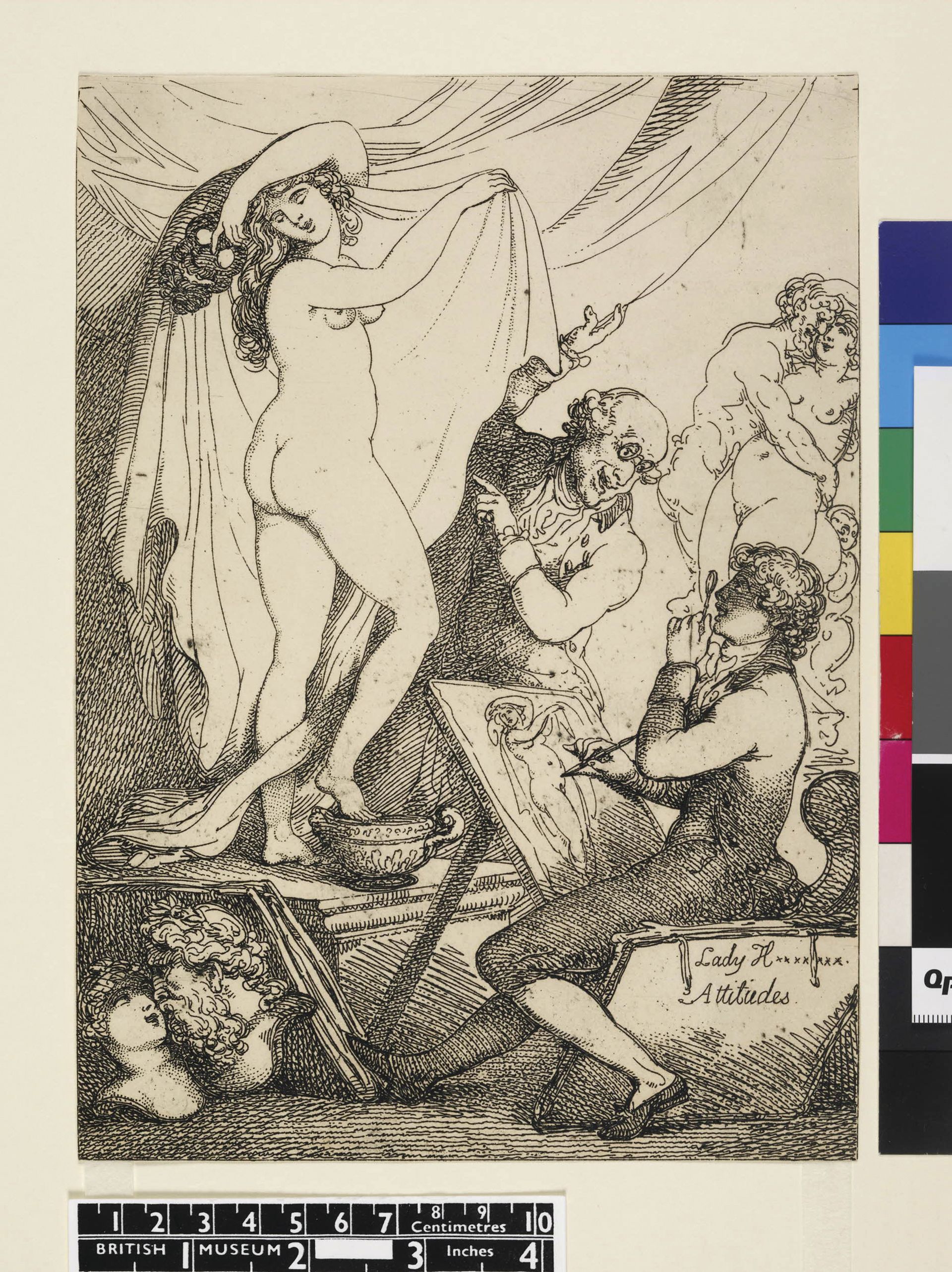

A “Breathing Statue” Hamilton told visitors that he loved Emma because she looked like an ancient beauty on one of his Greek vases. In turn, visitors called her a “Breathing Statue” or Hamilton’s “pantomime mistress”, his “gallery of statues”. Emma could be a whole gallery because she and Hamilton had invented a new art form, performances of “Attitudes”. Emma appeared before Hamilton’s guests in a specially made Greek-style dress, a shawl or two, and seductively unpinned hair, then took a series of poses, each with a different arrangement of shawl and hair, to imitate ancient mythological or historical characters such as Medea or Cleopatra: “With the assistance of one or two Etruscan vases and an urn, she takes almost every attitude of the finest antique figures successively,” wrote the politician and scholar John B. S. Morritt, “and varying in a moment the folds of her shawls, the flow of her hair; and her wonderful countenance is at one instant a Sibyl, then a Fury, a Niobe, a Sophonisba drinking poison, a Bacchante drinking wine, dancing, and playing the tambourine, an Agrippina at the tomb of Germanicus, and every different attitude of almost every different passion… This wonderful variety is always delicately elegant, and entirely studied from the antique designs of vases and the figures of Herculaneum.”

Hamilton’s antiquities came into play as accessories for these performances. Some guests noted in their diaries that he was nervous when Emma handled an ancient vase a bit too energetically. But most guests recorded their awe at Emma’s dramatic ability and the utter commitment of Hamilton: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe reported that “the old lord holds the lights for it and has given himself wholeheartedly to his subject”. The poet thought that Hamilton found in Emma “all the statues of antiquity, all the lovely profiles on the coins of Sicily”.

The lovely profiles on ancient coins do not speak, and neither did Emma during her Attitudes. Her silence was probably a key benefit to her chosen art form as she retained to the end of her life the Cockney accent that instantly revealed her childhood in the slums of London. Many visitors noted their disgust at hearing Emma’s voice, so ridiculously incongruous with her beauty and setting. They probably guessed at the past the voice belonged to—a miserable childhood followed by drudgery as a servant, first for a respectable family, then for questionable actresses in a theatre. Better to inspire thoughts of Cleopatra and other past beauties with questionable morals than thoughts of her own life. Better to be a living, mute statue.

Emma was such a fitting addition to Hamilton’s collection that he married her in 1791, when he was 60 and she was 26. The collector who would struggle home with a basket of newly excavated vases, their dirt rubbing on his silk and ermine robes, did not scruple at the stains on Emma’s reputation. Instead, he seemed to regard her as a special discovery that few were capable of appreciating, just as he frequently wrote that only a handful of connoisseurs could see the beauty of his ancient vases.

An admiring admiral Hamilton was right—there were many who failed to appreciate the new Lady Hamilton. Visitors to Naples, a far-flung and famously lax outpost, had been tolerant of the convenient fiction that Emma was merely Hamilton’s protégé. But now, a Cockney Lady Hamilton, dancing in shawls, appeared ridiculous. This was especially true if the visitors recalled Hamilton’s aristocratic first wife, a woman with a gentle temperament whose playing of the harpsichord a young Mozart, touring Europe, had described as “uncommonly moving”.

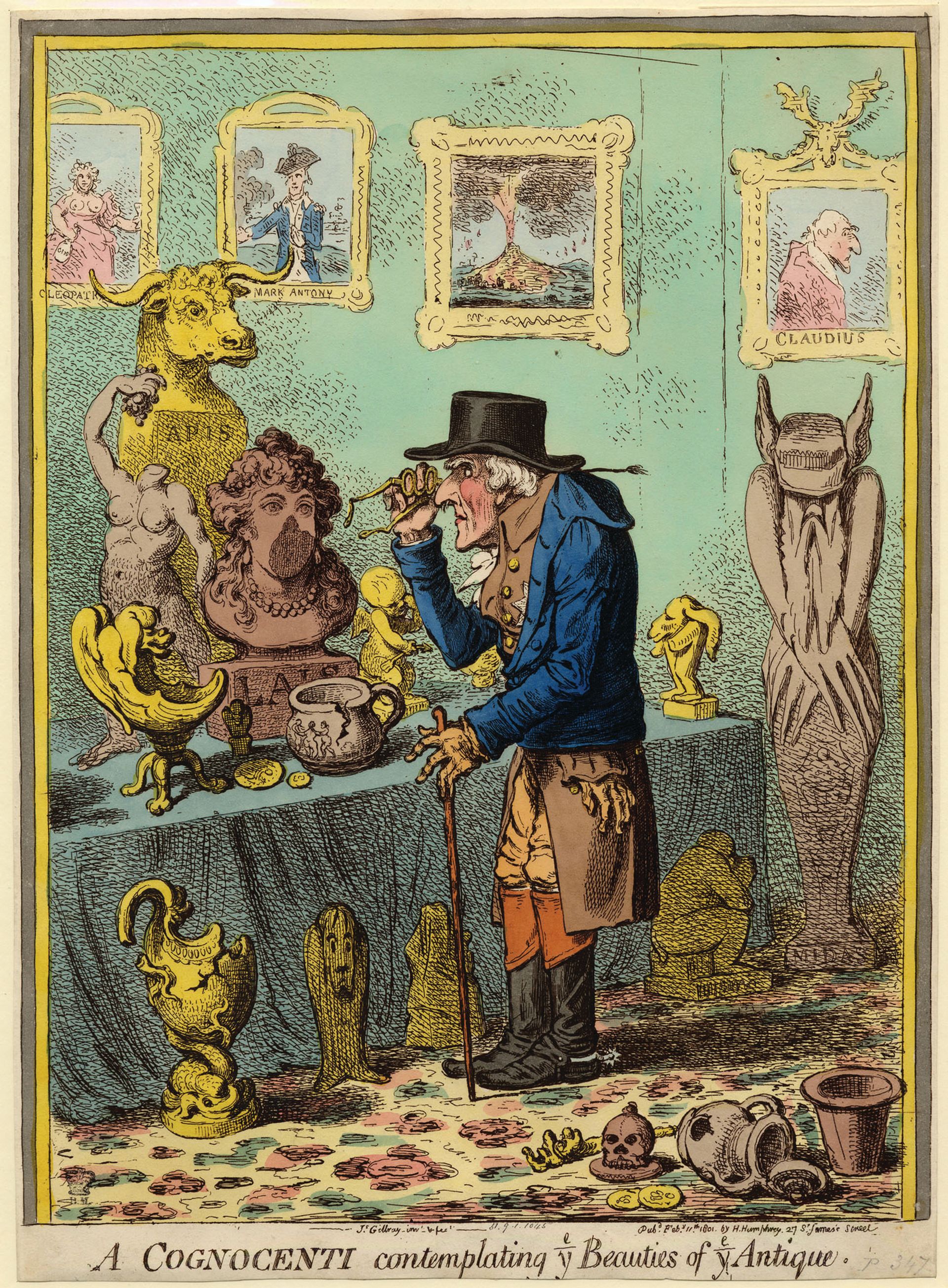

Disapproving visitors also recorded in letters and diary entries Emma’s increasingly zaftig appearance. Emma was losing her beauty, but Hamilton, the great connoisseur, did not seem to notice. Jack the monkey was dead, unable to survive the cold of another winter, and Hamilton, gazing lovingly at the former beauty, was as grotesque as Jack, pondering antiquities through a microscope. He was his own parody.

To some, at least, Emma still had her charms. Horatio Nelson, fresh from striking a devastating blow to Napoleon’s navy during the Battle of the Nile, was unable to resist her when he arrived in Naples in 1798. The gaunt Nelson, whose battle wounds had cost him an eye and his right arm, was an unlikely match for the plump lady of leisure, but her adoration won him. Hamilton, now in declining health and an admirer of Nelson, either fully tolerated or indeed had no idea about their affair. He permitted Nelson to remain a guest at his house and left no record of any reaction to the news that Emma was pregnant. She hardly bothered to make a secret of her daughter’s parentage, naming her Horatia (although that could also have been interpreted as a general tribute to the hero without his personal involvement). Hamilton even resigned his ambassadorship and moved back to England in 1800, seemingly because Emma wanted to follow Nelson when he left Naples. They lived together—Hamilton, Nelson, Emma, and her mother—in a house paid for by Hamilton.

Their strange arrangement caused endless scandal. Caricaturists published parodies of the trio. One showed an obese Emma, surrounded by bottles, scattered antiquities in licentious poses, and a deeply slumbering husband, mourning the departure of Nelson as if in one of her Attitudes, impersonating Dido, the tragic queen of the Aeneid, who threw herself on a funeral pyre when her lover sailed away. Another shows the withered Hamilton, peering shortsightedly at a broken Roman statue and ignoring the cavorting of Emma and Nelson, shown as portraits of Cleopatra and Mark Antony, his gloves falling limply out of his pocket to symbolise his lack of sexual ability.

Debt collection Hamilton’s limited energies were taken up by other matters during these last years of his life. There were his vases to mourn—he had sold a first collection, some 730 vases, to the British Museum in 1771 to meet his debts and a part of his second had gone down with the ship transporting them to England. Hamilton was horrified because he believed that “my Collection wou’d have given information to the most learned & have convinced every intelligent Being that there is but one Truth, & that God Almighty has never made himself known to the miserable Atoms that inhabit this globe otherwise than bidding them to increase & multiply & to leave the rest to Him—So thought the Wise Ancients when the Mysteries of Bacchus & Eleusis were established”.

And there were his debts. He was constantly writing petitions and making visits to ask for reimbursement for expenses incurred during his years as ambassador. He was always surprised at his failure to obtain more funds, blind to the possibility that his superiors would consider the huge amounts he spent on art a clear demonstration that he had had enough.

Or perhaps he saw but did not care. Certainly he did not trouble himself much about Emma’s future; he died in 1803, leaving her only a small pension. Nelson was killed in the Battle of Trafalgar two years later. His stated desires that the state provide for Emma as if she were his widow were pointedly ignored, and she was left in debt for the rest of her life. Of all of the products of Hamilton’s life and work, only the antiquities retained their serenity and beauty.

• This is an adapted excerpt from Possession: The Curious History of Private Collectors from Antiquity to the Present by Erin L. Thompson, published in May by Yale University Press. Reproduced by permission