This time last year, the six evening auctions at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips saw a combined total of almost $2.5bn worth of art sold, as the market was pushed to levels that some in the trade saw as unsustainable. A year later, the volume of sales was less than half that figure—around $971.7m. This year’s curated sale at Christie’s, Bound To Fail, fetched $78.1m (including fees), while last year’s equivalent sale, Looking Forward to the Past, notched up $705.9m (with fees), almost ten times as much.

What has happened since May last year? Oil prices have fallen, volatile stock markets have underperformed, political insecurity straddles both sides of the pond, and China’s growth has slowed. “You can’t expect stellar prices and stellar bidding in this climate,” says the art adviser Thomas Seydoux.

The media has been keen to proclaim doom and gloom but, barring the underwhelming results of the Impressionist and Modern sale at Sotheby’s (a 66% sell-through rate and some high-profile lots unsold), and the clearly smaller volume of top-end consignments, this season’s sales were solid, with sell-through rates otherwise ranging from 87% to 97%. Collectors were buying, they just weren’t as trigger-happy as last year.

“Several objects were in strong demand, and the market responded aggressively,” says Matt Carey-Williams, Phillips’ deputy chairman for Europe and Asia. “People still have the money, but the landscape is more risk-averse.”

Amid more muted buying, records were set for artists including Maurizio Cattelan, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Auguste Rodin, Mike Kelley, Agnes Martin, Richard Prince, Kerry James Marshall, Sam Francis, Günther Förg and Takeo Yamaguchi, showing that the strength and depth of bidding lie primarily in the market for contemporary art.

Good reserve prices “The three Ds [death, divorce and debt] were not sufficient to meet demand last year, so a fourth option was introduced: opportunity. Guarantees encouraged unexpected consignors to sell their art publicly,” Seydoux says. Last year, for example, Christie’s guaranteed (in other words, effectively pre-sold) more than half the lots in its post-war and contemporary and Looking Forward to the Past sales.

“In general, auction houses across the board took on less risk this season,” says Sara Friedlander, a vice president and head of the contemporary evening sale at Christie’s, adding: “Depth of bidding is accomplished by lowering the reserve. You want people to feel the excitement of possibility in the room.”

Sotheby’s took the only hit of the season in its Monday auction of Impressionist and Modern art. A third of the works failed to find buyers, and when Picasso’s Femme dans un fauteuil (1962-63) failed to sell on a $4.9m bid, against a lower estimate of $5m, the heads of the other evening sales must have taken note. The next sales saw many more lots selling comfortably below estimate, with auction staffers admitting to spending the day on the phone with consignors as they tried to manage their expectations.

“It’s a tricky market to work in,” says Jeremiah Evarts, a senior vice president at Sotheby’s and head of the Impressionist and Modern art evening sale. “There were no big engine-driving estates this season.” Couple that with buyers’ caution and a sale might not go as planned.

Absence of big hitters felt Most New York auction seasons feature major collections that anchor the rest of a sale. However, this season suffered from the lack of big estates. At the Christie’s press preview, one specialist remarked that it was the first Impressionist and Modern sale in New York since 2007 that didn’t have one. Such things are a matter of chance (since many works from big collections come to market to help pay for estate taxes), and it meant that the houses had to work even harder to secure individual lots.

“That’s a great asset for us, using those collections as a tool to persuade other collectors,” says Brooke Lampley, senior vice president and head of the Impressionist and Modern evening sales. She notes that 2014’s sale of works from Huguette Clark’s collection helped secure many other works for the sale. “People want to know as much as possible about the context in which they’re offering their works. When you have great collections you can talk about, it’s just reassuring to other consignors.”

Thin bidding at the very top While there was enough depth of bidding, in general, for mid-range, seven-figure works, things did not look as rosy for top lots. Christie’s set a record for Basquiat’s Untitled (1982), which sold for $51m ($57.3m with fees), well above its estimate of around $40m, but most eight-figure works didn’t do so well, selling just within estimate, if not below. On the same night, Mark Rothko’s No.17 (1957), estimated at $30m to $40m and with no guarantee, drew few bids and went for $29m ($32.6m with fees). Renoir’s Madame de Galéa à la méridienne (1912), estimated at $8m to $10m, was bought in with no bids.

Similarly, at Sotheby’s a particularly fine marble version of Rodin’s L’Éternel Printemps (1901-03) soared past its upper estimate of $12m and sold for $18m ($20.4m with fees), a record for the artist, but Cy Twombly’s Untitled (New York City) (1968), which had been off the market since 1969, sold for $32.5m ($36.7m with fees), well below its estimate of around $40m. The other big Twombly in that sale, Untitled (Bacchus, 1st Version V) (2004), which had never been to auction before, sold for $13.5m ($15.4m with fees), against an estimate of around $20m. André Derain’s Les Voiles rouges (1906), estimated at $15m to $20m, failed to find a buyer.

Would these kinds of works have fetched a higher price, or indeed sold, this time last year? “When there is hesitancy in the market, it’s usually manifested in a certain value bandwidth,” Evarts says.

Passion from the pacific Asian bidding is a perennial fascination during auction season, but this year there was more than usual reason to pay attention to it. The biggest bids came from Yusaku Maezawa, the Japanese fashion entrepreneur and billionaire, who spent $98m over the course of the week. His purchases included Adam Lindemann’s record-breaking Basquiat, Richard Prince’s Runaway Nurse (2007) for $8.5m ($9.7m with fees) and Jeff Koons’s Lobster (2007-12) for $6m ($6.9m with fees), all at Christie’s. At Sotheby’s, he bought Adrian Ghenie’s hotly contested Self Portrait as Vincent Van Gogh (2012) for $2.2m ($2.6m with fees) and Christopher Wool’s Untitled (1990) for $12.2m ($13.9m with fees). He posted most of these purchases on Instagram.

Auction house honchos were quick to say that this wave of Japanese auction buying is more than just an Eighties revival. “While there’s an appearance that the market may have thinned, we see those who are players coming on very strong, and that’s pan-Asia,” Sotheby’s Amy Cappellazzo told CNBC, noting that the house had its highest number of Asian bidders since 2004. Behind the prices: our selection

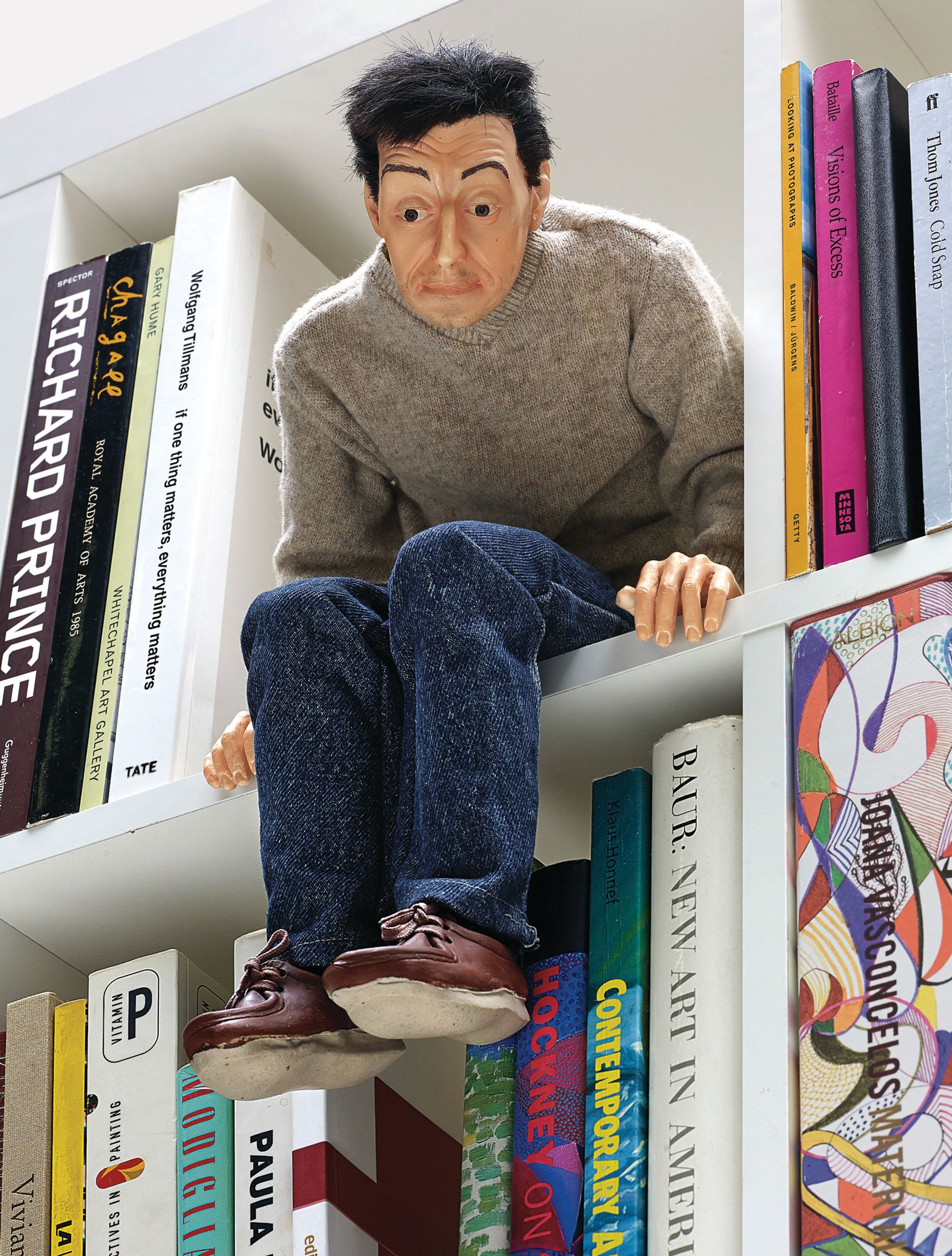

Maurizio Cattelan, Mini-me (1999)

Sold at Phillips, 8 May, for $620,000 ($749,000 with fees; est $400,000-$600,000)

The Italian artist’s sculpture of Hitler fetched a record price at Christie’s, while his installation at Frieze, which included a live donkey, was one of the fair’s main draws. His Mini-me sculpture was perched above the front desk at Phillips ahead of the sale. “We couldn’t have asked for a better time to sell this work, and it’s a great example of what the artist is all about,” Matt Carey-Williams says. “It’s almost a mascot of the work we [Phillips] do. We may not deal with the biggest works, but we deal with the biggest brand names.”

David Hammons, Stone Head (2006)

Sold at Christie’s, 8 May, for $850,000 ($1m with fees; est $800,000-$1.2m)

If this work looked as if it came right out of Mnuchin Gallery’s Hammons show, that’s because it did. It was consigned directly after the show, according to the New York Times. Loic Gouzer, Christie’s deputy chairman, said there was “nothing very unusual” about this, but it’s not very common either. Many wondered whether there would be difficulties securing commissions for this season. Few lots (not including this one) were guaranteed in this sale, although this felt pre-arranged: it hammered near its low estimate with just two bidders: Gouzer, on the phone, and Mnuchin himself.

Claude Monet, Marée basse aux Petits-Dalles (1884)

Sold at Sotheby’s, 9 May, for $8.6m ($9.9m with fees; est $3m-$5m)

“There was global bidding on this painting,” Jeremiah Evarts says. This was one of the few works from a big collection, consigned by the estate of the pharma entrepreneur Elmer Bobst and his wife Mamdouha. Monet’s landscapes aren’t usually this brightly coloured, which perhaps explains why bidding was so fierce. “It was on the same wall for around 50 years. When we took it off the wall, there were marks on the wallpaper behind it. We actually estimated the work before we cleaned it—we found all this light that wasn’t there before,” Evarts says.

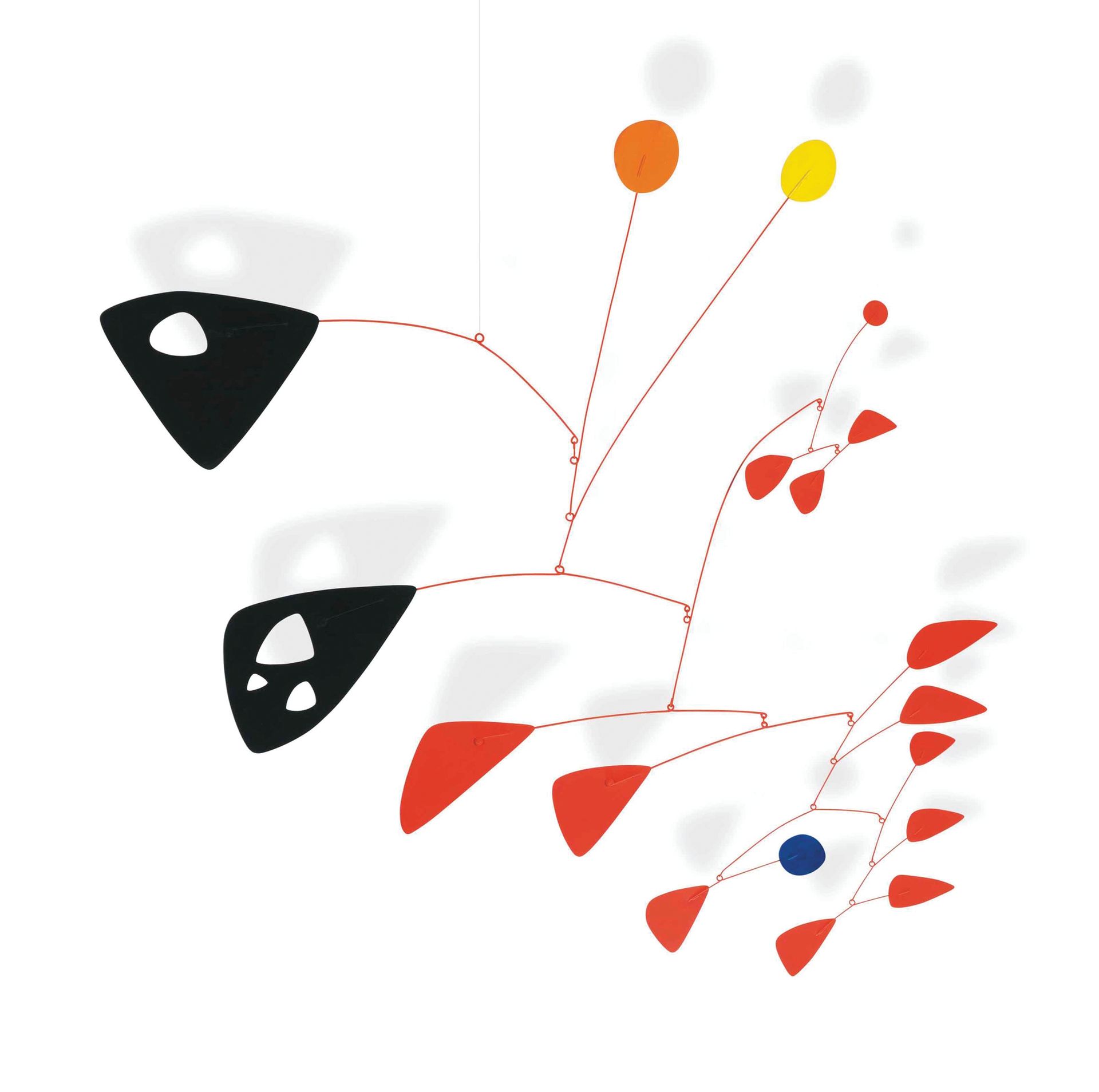

Alexander Calder, Untitled (1952)

Sold at Christie’s, 10 May, for $3.2m ($3.7 with fees;

est $2.5m-$3.5m)

A group of nine works by Calder were consigned from the collection of Gira Sarabhai, of the prominent Sarabhai family, from Ahmedabad, in Gujarat. She commissioned them directly from the artist, whom she invited to come to India with his wife. They have never been on the market before, and only a few of them were shown at London’s Ordovas Gallery in 2012. “Some pieces were bid on by the same collectors,” Sara Friedlander says, “and understandably so—they hang together so beautifully.” Together, the works were estimated at $25.6m to $37.1m. They fetched $21.1m (around $26m with fees, with one lot bought in).

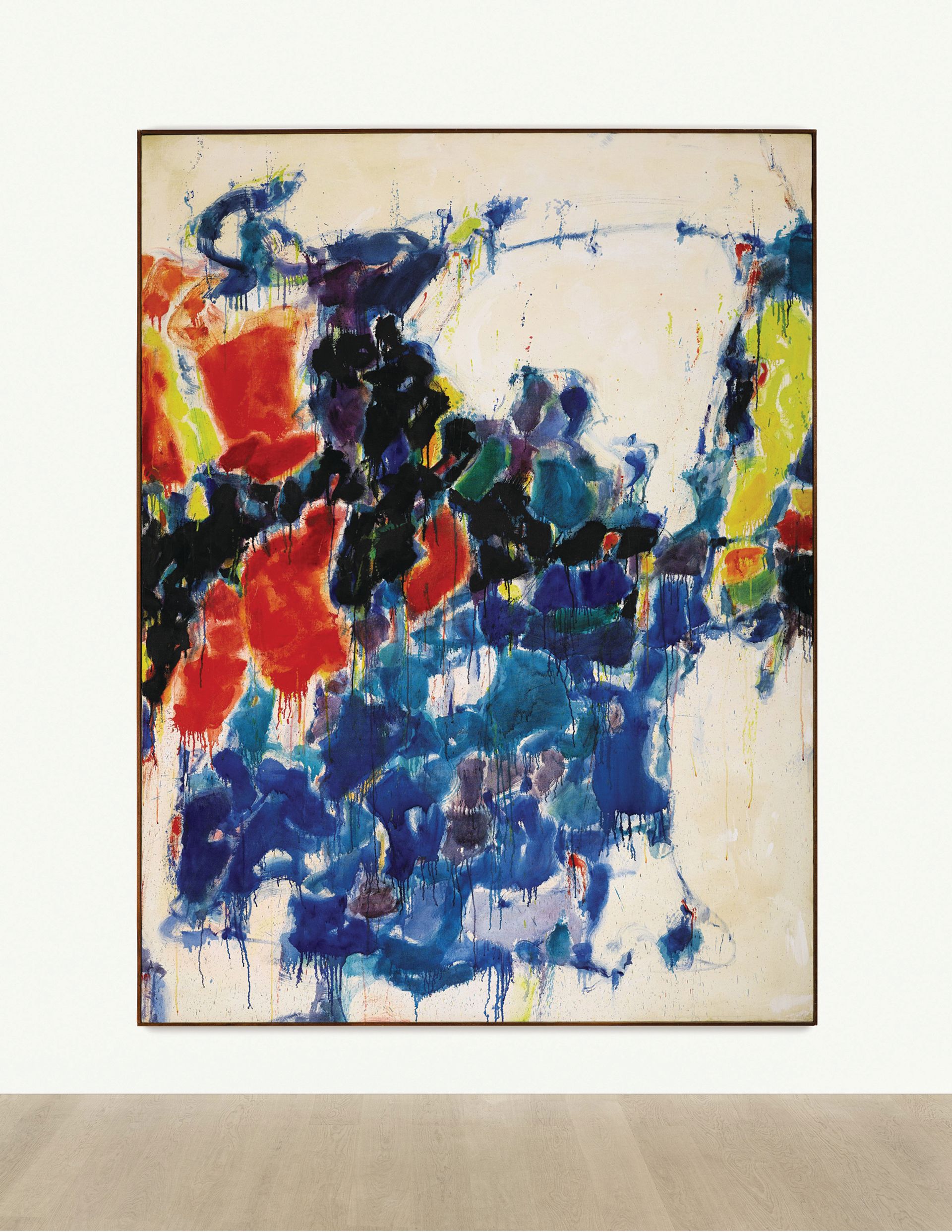

Sam Francis, Summer #1 (1957)

Sold at Sotheby’s, 11 May, for $10.4m ($11.8m with fees; est $8m-$12m)

Sotheby’s contemporary sale had a 95% sell-through rate, its highest in seven years. Guarantees were used strategically to secure the bigger lots, while mid-range items did well on their own. One of the evening’s higher-end standouts—and the only record from that sale—was Summer #1 (1957), which saw four phone bidders competing before it was bought by Eli Broad, in the room, for mid-estimate. “It’s the front cover of the catalogue raisonné,” says Michael Macaulay, the head of evening auctions, though he declined to say anything about the seller. “Consequently, its pricing was always going to be a recalibration of the market for Sam Francis.”

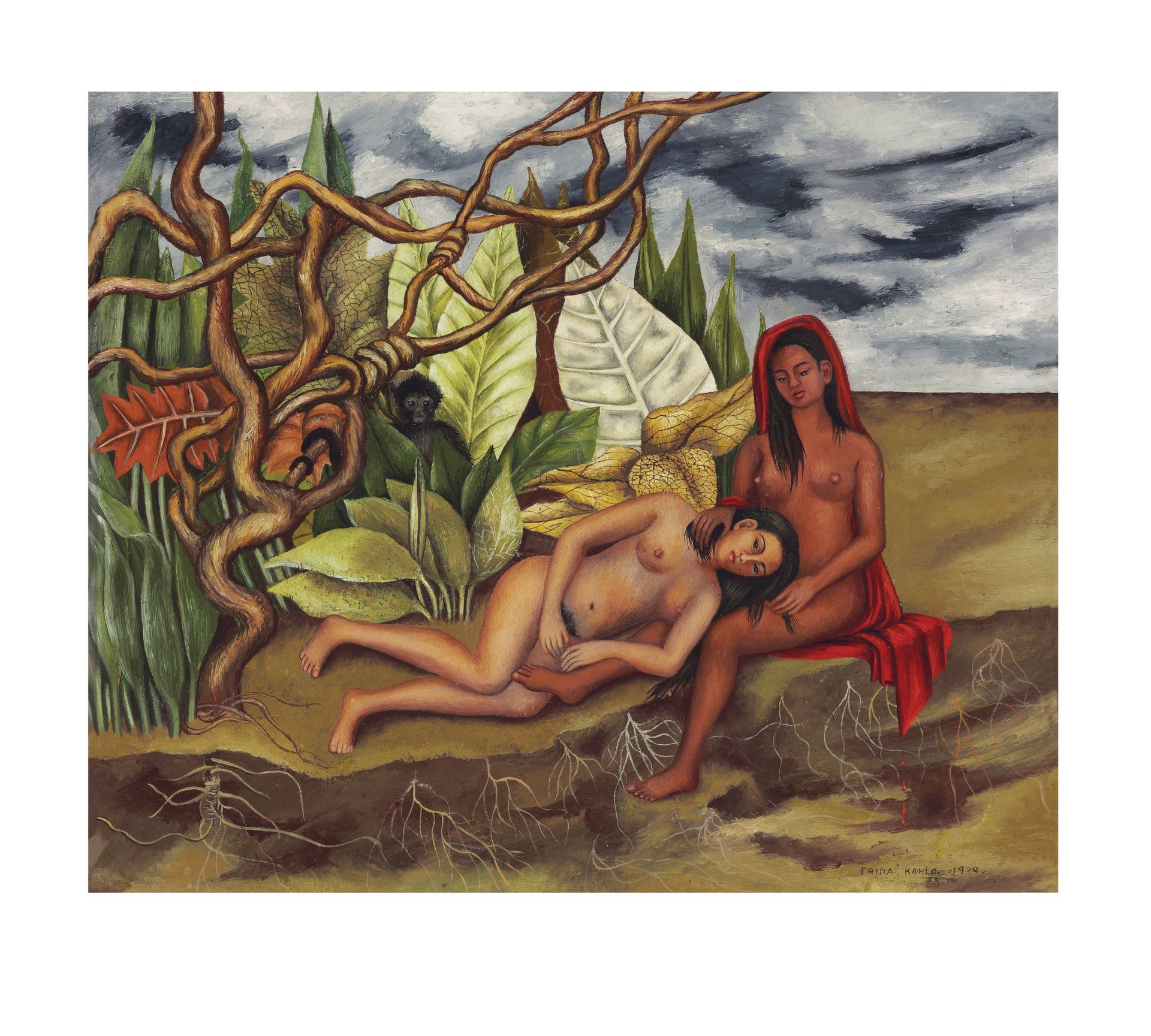

Frida Kahlo, Two Nudes in the Forest (The Land Itself) (1939)

Sold at Christie’s, 12 May, for $7m ($8m with fees; est $8m-$12m)

One of the records achieved during sales week was for Frida Kahlo’s Two Nudes in the Forest (The Land Itself) (1939). Christie’s wasn’t surprised, as such a price is not uncommon on the private market. The seller had, in fact, been touting the work on the private market for a much higher price before going to auction. “The market was aware of the work,” said Brooke Lampley, adding that her clients often ask about Kahlo. “This was a very important event,” she said. “Her market is ripe for revision, as is the market of a lot of great female artists.”

Auction results New York

8-12 May

Impressionist and Modern

Sotheby’s

9 May

Hammer: $123.4m

With fees: $144.5m

Estimate: $164.8m-$235.8m

Sold by lot: 66%

Christie’s

12 May

Hammer: $121.9m

With fees: $141.5m

Estimate: $134.3m-$203.4m

Sold by lot: 86%

Post-war and Contemporary

Christie’s

Bound to Fail

8 May

Hammer: $67m

With fees: $78.1m

Estimate: $59m-$81m

Sold by lot: 97%

Phillips

8 May

Hammer: $39m

With fees: $47m

Estimate: $41m-$61m

Sold by lot: 92%

Christie’s

10 May

Hammer: $277.4m

With fees: $318.4m

Estimate: $280m-$393.2m

Sold by lot: 87%

Sotheby’s

11 May

Hammer: $209.6m

With fees: $242.2m

Estimate: $201.4m-$257.5m

Sold by lot: 95%