Bosch fever is now moving on to Madrid, where the most comprehensive exhibition ever held on the Dutch master opens today (31 May). Twenty-four works by Hieronymus Bosch (around 1450-1516) are on display—seven more than were at the Noordbrabants Museum in s’Hertogenbosch earlier this year. Probably never again will so many of his paintings be brought together.

An intense rivalry has developed between the Dutch and Spanish venues which mounted exhibitions to mark the 500th anniversary of Bosch’s death. At the Madrid press launch, the Museo Nacional del Prado mounted a robust attributional defence of several of its paintings which had been rejected by the Noordbrabants. Most exhibition catalogues start off with profuse thanks to numerous specialists, but the Prado’s volume expresses little gratitude to the Dutch experts.

Both retrospectives were arranged independently, although the two museums did at least coordinate dates with a three-week gap between the shows, so loans could be shown in the two museums. The transport arrangements worked smoothly, and Bosch’s oeuvre was safely moved from s’Hertogenbosch to Madrid in mid-May. Each picture was transported separately and, although adding to costs, this avoided any risk of virtually all the oeuvre being lost in a single catastrophe.

The Prado also succeeded in borrowing three pictures which the Noordbrabants Museum had failed to get. The St Anthony triptych has come from Lisbon’s Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, which in return received the Prado’s Dürer self-portrait (1498) on loan until 18 September. London’s National Gallery sent its Christ Mocked to Madrid (surprisingly, it did not also lend to s’Hertogenbosch, the artist’s home town). Despite last year’s row between the Prado and the Patrimonio Nacional over who should normally display the Garden of Earthly Delights, the museum’s relations with the government heritage agency have since improved and Christ carrying the Cross was lent from the Escorial.

The Prado is missing only three works by Bosch. The Last Judgment triptych at Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts and the Crucifixion at Brussels’ Royal Museums of Fine Arts cannot travel for conservation reasons. Venice’s Accademia Gallery is not lending the Hermit Saints triptych (which did go to the Noordbrabants)—although it has sent its other Bosch, the Visions of the Hereafter.

Disputed attributions

However, part of the difference between the Bosch numbers at the Noordbrabants and the Prado is because of attributional questions. Dutch researchers demoted four works, all Spanish-owned pictures. The Noordbrabants team numbered the authentic works as 24 (of which they got 17). The Prado specialists regard the total of fully-attributed works as 27 (of which they got 24). (These figures are based on treating four panels from the Wayfarer altarpiece in different collections as separate works.)

The Noordbrabants was initially promised one of the disputed Spanish pictures, Extracting the Stone of Madness. In the loan agreement of last September it was described as “by Bosch”. But the Dutch museum later advised the Prado that it would be shown as from the workshop or by a follower, dating to 1500-20. The Prado was annoyed, and withdrew the loan. “It is unacceptable to request a painting as a Bosch and then show it as something different”, Miguel Falomir, the museum’s deputy director, told The Art Newspaper.

Extracting the Stone of Madness is now on display in Madrid as by the Dutch master, dated to 1501-05. The Prado catalogue explains that although the underdrawing technique is slightly different from other Bosch paintings, this was because of the way the artist approached the commission for Philip of Burgundy.

The Dutch scholars also rejected the Prado’s Temptation of St Anthony, ascribing it to a follower and dating it to 1530-40, several decades after Bosch’s death. Among evidence cited are the cartoon-like monsters (one in the lower left appears to be smiling). Pilar Silva, the Prado’s curator, rebuts this and suggests that the monster is actually licking its lips in anticipation of attacking the saint. She argues that a technical examination and infrared images confirm that the picture is by Bosch (citing, for example, the modeling of the snout of the pig).

Dendrochronology gives a date for the oak panel as 1464. The Prado’s panel has also been conserved for the show, with the uppermost part of its arched top reinstated. The Prado now dates the painting to 1510-15.

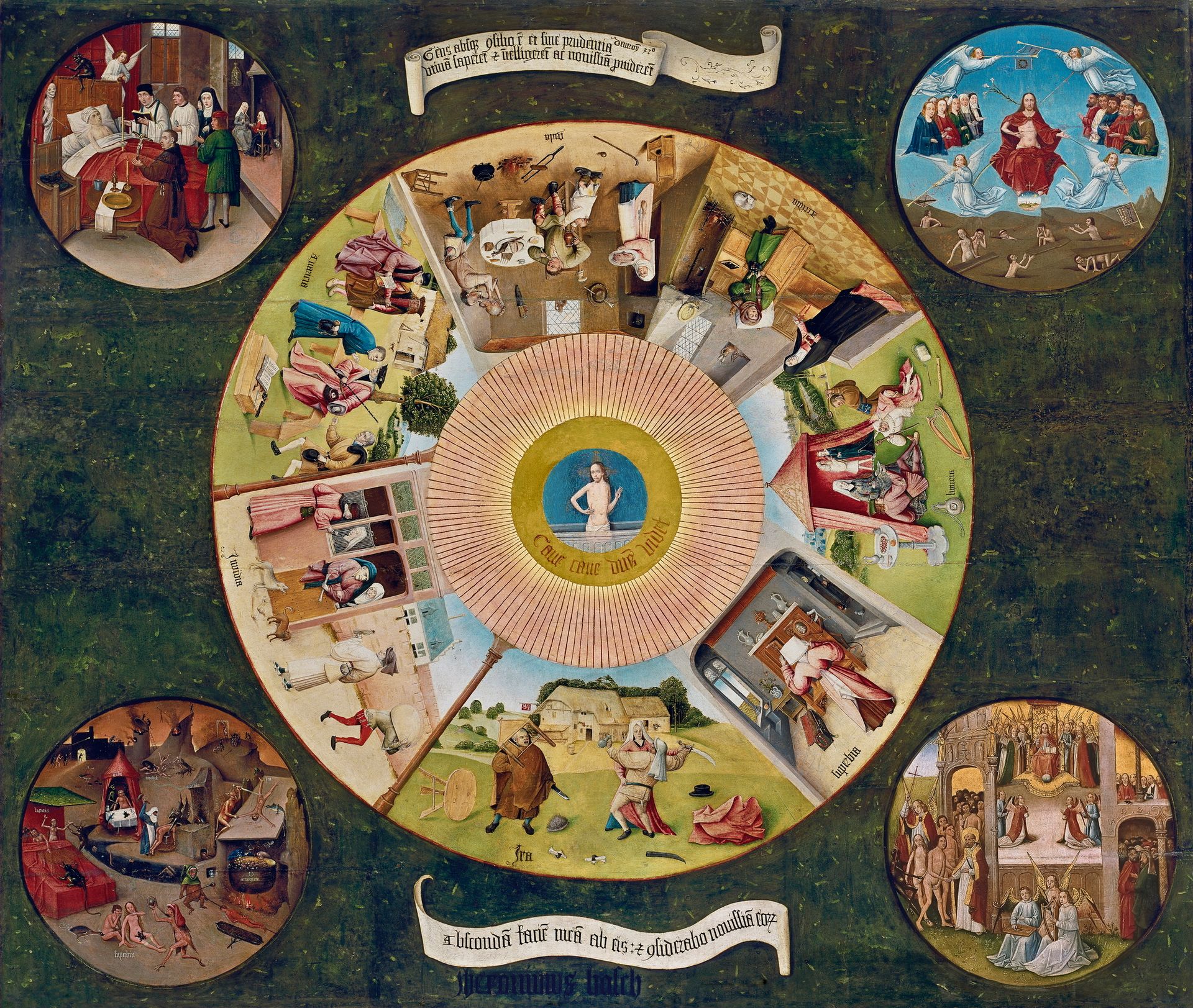

The third work rejected by the Dutch specialists is an unusual object, a painted table top, the Table of the Seven Deadly Sins, arguing that it is from the workshop or a follower, dating it to 1510-20. The Prado has now published infrared images which show considerable changes in the underdrawing, particularly for the images of Pride, Greed and Wrath. The Prado sees this as evidence of Bosch’s hand and dates it to 1505-10.

But the greatest and undisputed painting in the Madrid show is the Prado’s Garden of Earthly Delights. This triptych was simply too important to lend to the Noordbrabants, and it attracts more visitors than any other work in the Madrid museum. The Prado dates it to 1490-1500 (with the Dutch specialists making it slightly later, 1495-1505). In 1605 it was described by friar José de Sigüenza as capturing the “short-lived taste of the strawberry, and its scent that one barely appreciates before it has passed”. The message is that mankind must resist the ephemeral temptations of the flesh.

This enigmatic work is still revealing its secrets. The Prado catalogue notes that the lone figure of an upside-down man holding his genitals (presumably representing masturbation) has his hands in the gesture of prayer. New infrared images reveal minor changes to the composition, including the removal of a pomegranate in the lower left corner of the main panel.

Despite the differing approaches of the Dutch and Spanish curators, the two exhibitions represent a leap forward in terms of scholarship. Along with their exhibition catalogue, the Dutch Bosch Research and Conservation Project has just published a two-volume catalogue raisonné and technical volume with 1,060 pages. The Prado’s 400-page catalogue is packed with detail. All these publications are available in English.

The two Bosch exhibitions are likely to be among the most popular of this year. The Noordbrabants Museum show (January-April) attracted 422,000 visitors, an astonishing number for a city with a population of less than half this figure. The Prado is expecting well over 500,000. The two venues are therefore likely to attract at least a million visitors. The Prado exhibition is sponsored by Fundación BBVA.

• Bosch: The Fifth Centenary Exhibition, until 11 September, Prado, Madrid