Magical Surfaces: the Uncanny in Contemporary Photography, Parasol Unit (until 19 June)

The Freudian notion of the “uncanny”—which the great man described in 1919 as “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar”—is now a well stomped-upon creative territory, especially in the realm of photography. But this generation-spanning seven-artist show confirms that even in our jaded post-Freudian image-overloaded era, we can still be treated to a disquietingly unheimlich frisson.

All-American 1970s normality is subtly and sometimes dramatically subverted in the subconscious tweaks provided by Joel Sternfeld’s crisply deadpan and tragicomic real-life scenarios, or in the eerily empty Americana vistas of the artist-photographer Stephen Shore. But by far the most chilling clash of familiar/unfamiliar comes from David Claerbout’s extraordinary 2015 reconstruction of a 3D Elvis, digitally conjured out of a vintage photo showing the young, pre-fame King, wearing just a pair of shorts and relaxing at home with friends and family. Not only does the resulting animation flesh out the figures by disquietingly placing them in real space, but the way in which the camera also intimately and excruciatingly scrutinizes every inch of this most famous of bodies causes one’s own flesh to creep in sympathy.

Helen Mirra and Allyson Strafella: Suchness, Large Glass (until 24 June)

Each of these two artists kept examples of each other’s artworks in their studios to act as quiet inspiration while making their own pieces. And this subtle, slow burning but utterly arresting show is the result of the crossover conversations that reverberated between Massachusetts-based Helen Mirra’s weavings and the typewriter drawings made by Allyson Strafella in Hudson, New York.

The longer you look, the more the affinities become evident in the shapes within Mirra’s small woven compositions in wool and linen, and the inky patches created by repeated hammerings and dense build-up of Strafella’s typed marks into fragile, and at times disintegrating, sheets of paper. Despite—or maybe because of—their small size, sombre colour range and retiring abstract forms, both these sets of works pulse with a quietly resonating presence that also testifies to the profound degree of empathy between both artists.

George Shaw: My Back to Nature, National Gallery (until 30 Oct)

Blighted woodlands punctuated by piles of beer cans, shredded porn and vandalised trees comprise George Shaw’s highly personal and contemporary response to the leafy glades and Arcadian backdrops to so many of the National Gallery’s Old Master paintings. The works are faithfully painted in hobbyist Humbrol enamels directly from photographs of the neglected woods near the artist’s childhood home on a West Midlands council estate. These neglected fly-tipped corners and their grim detritus become charged with a bleak poetry that chimes convincingly with the predilection of earlier painters to set their classical and biblical scenes of seduction, hedonism and assassination in the most sylvan of settings.

In Shaw’s glumly intense paintings the most grungy of contemporary subject matter—fleshy pinups scattered on the grass, cascading folds of blue tarpaulin draped across a branch, a splat of red paint on a tree trunk—assume a time-honoured art historical resonance, while the artist portrays himself making his irreverent mark by peeing up against a tree.

Tomma Abts, Greengrassi (until 18 June)

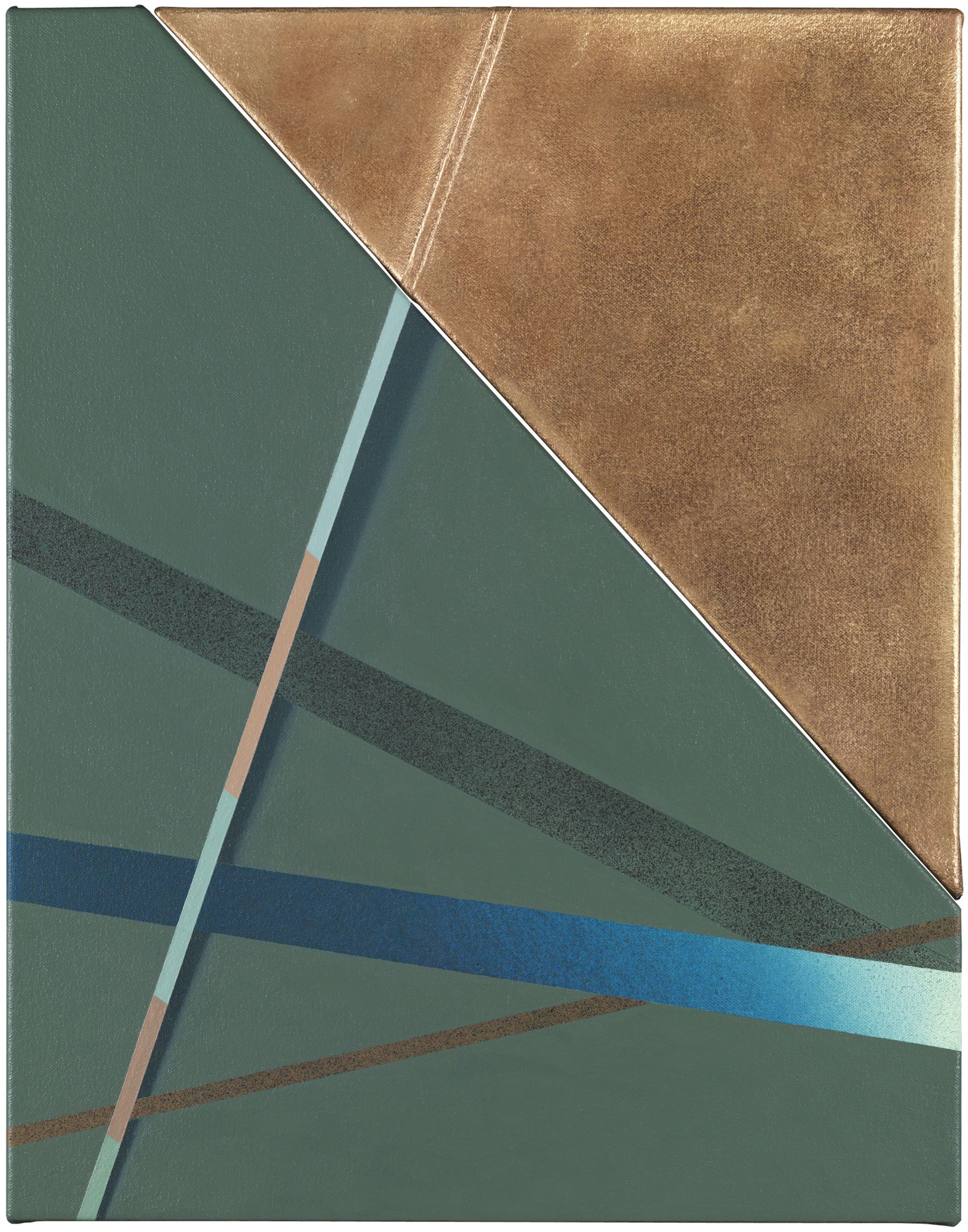

The deceptively unassuming abstract paintings of Tomma Abts act like artistic stealth bombers. Don’t be deceived by their low profile demeanour, their palette of oddly nostalgic off-kilter colours or the way in which their crisp blocks, stripes and circles and mysterious onomatopoeic names seem like the product of some long-forgotten Futurist or member of the Dessau Bauhaus.

For, as her most recent work confirms, closer scrutiny confounds any easy readings to reveal a very contemporary knowingness of how paint can perform. In these paintings what appear to be straightforward relationships of form and colour are actually anything but. Intricate masking, layering, shading and spatial games complicate the picture plane in mind-boggling ways, frequently flipping the same shape between two and three dimensions and then back into a void. The more time you spend in their company, the stranger and more perplexing they are. Oh, and just to confound you further, sometimes what looks like painted canvas is in fact cast bronze.