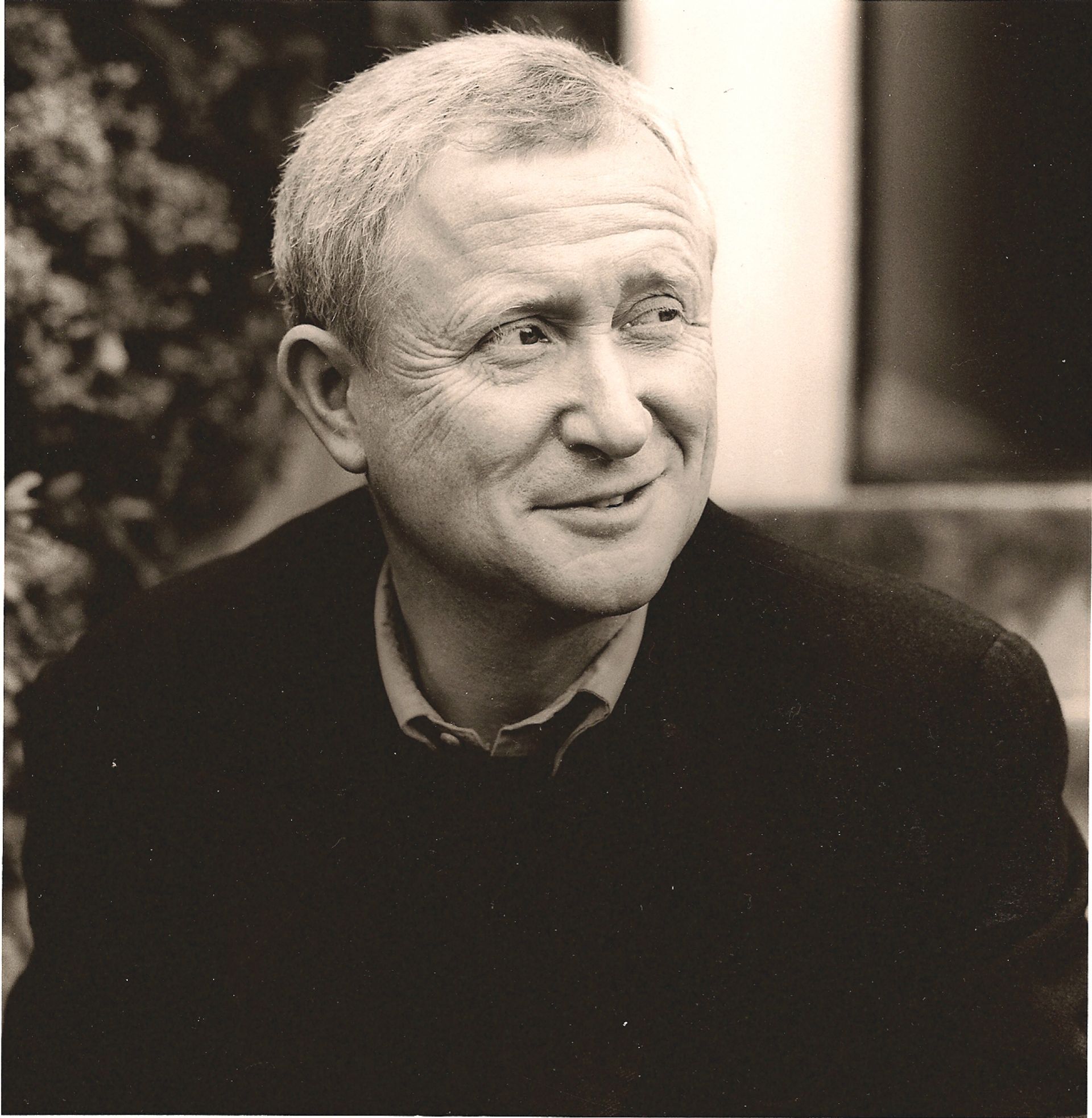

Hartwig Fischer, who took over last month as director of the British Museum, will find that Neil MacGregor is a hard act to follow. During his 13-year tenure, MacGregor’s global vision and outstanding communication skills raised the museum’s international profile and made antiquities relevant to a new generation. But no director can be a master of all arts. There is plenty to be done at the UK’s largest and most popular museum, which drew a record 6.8 million visitors last year. Here are four of the most pressing issues Fischer is facing.

1. Sponsorship On his first day, 4 April, Fischer was greeted by a protest letter calling on the museum to sever ties with the oil company BP. More than 100 influential names signed, including the actor Emma Thompson, Labour’s shadow chancellor John McDonnell, and Julian and Mark Sainsbury, the chairmen of two Sainsbury trusts. (The family is a major donor to the museum; other family trusts donated £25m two years ago for the Sainsbury Exhibition Galleries.)

The British Museum is facing renewed pressure after BP announced in March that it would end its sponsorship of the Tate. The company says the decision reflects “the extremely challenging business environment”. The British Museum will not reveal the level of BP support, but it is estimated to be about £250,000 a year until 2017, according to media reports. A museum spokeswoman says: “Discussions regarding the renewal of the partnership are continuing.”

2. Abu Dhabi loans Fischer will have to consider the sensitive issue of long-term loans to Abu Dhabi’s Zayed National Museum. Around 500 objects have been earmarked for loan, for a substantial fee, possibly from next year. Objects on the list include seven Assyrian reliefs similar to those destroyed by the Isil in Nimrud and a set of ten drawings (1532-43) by Hans Holbein the Younger.

3. Olympicopolis- bound? Another key issue will be a new storage facility, following the government’s decision to sell off Blythe House in west London. The British Museum is considering the establishment of a new store at Olympicopolis, the planned cultural centre on the 2012 Olympic site in east London.

4. New displays Fischer’s fundamental challenge will be to rethink the presentation of the permanent collection. Some displays now need updating and other parts of the collection deserve more space. Select renovation projects are already in the works, including new galleries for Oriental antiquities, Amaravati sculptures and Chinese jade, opening in 2017, and the Islamic collection, in 2018. Fischer must also make a decision on how to use the Round Reading Room, which was closed nearly three years ago. A consultation on its future is expected later this year. The most likely use would be as some sort of introduction to the collection.

An expert opinion Giles Waterfield, a museums expert and a former director of Dulwich Picture Gallery, praised Neil MacGregor for building a distinguished programme of temporary exhibitions with both scholarly and popular appeal. But he believes that the museum’s collection did not get the attention it deserved during his tenure.

Waterfield says: “What remains disappointing is the experience of visiting the permanent galleries. Individually splendid though many of them are, there is a sense of fragmentation, almost of incoherence, as one penetrates these sometimes daunting spaces. In contrast to many recent museum displays (such as the Ashmolean in Oxford), barriers between the disciplines at the British Museum are as rigid as ever.

“On arrival, nothing really prepares the visitor for what they are about to see and the Great Court remains stubbornly cold and impersonal, like a very grand bus station. The Great Hall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York makes a striking contrast.”