Those who are really in-the-know about places where art history and the thinking of the past are studied venerate the Warburg Institute. It may be a dreary 1950s University of London building but it houses a unique library that is extraordinary in its rich esotericism, including subjects that modern thought had consigned to the bin of intellectual dead ends or superstition, such as astrology, alchemy, secret codes, fortune-telling and magic.

To understand the past, you must know what furnished people’s minds, believed the library’s founder, Aby Warburg. He figured out the way in which Indian astrology was transmitted via Egypt and then through Arabic scholars to enter the Western astrological tradition, which was then taken up in tarot cards and the 15th-century frescoes on Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, which no one had understood until he managed to interpret them.

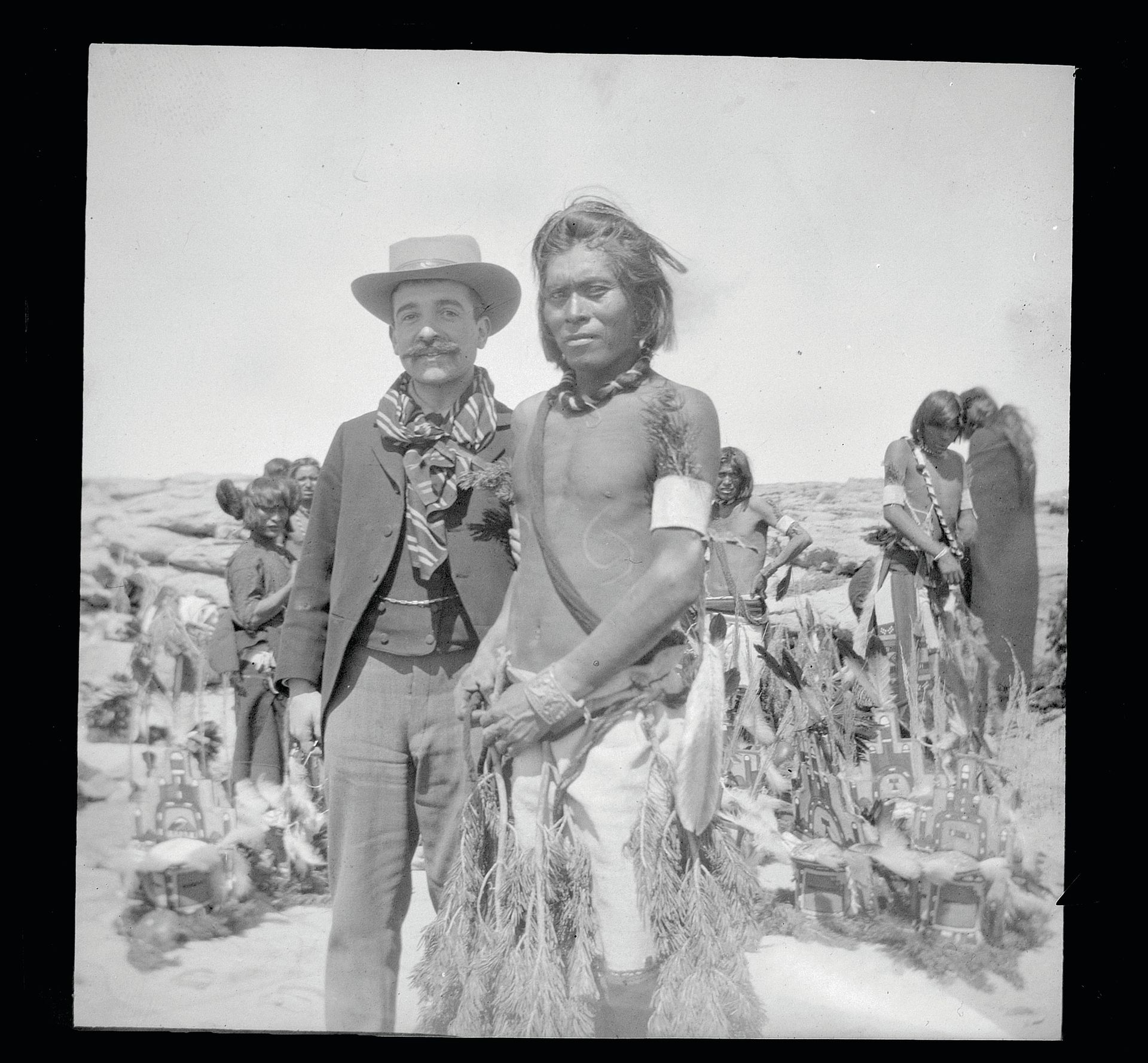

He also believed that you needed to understand cultures different from our own, so he worked both on the Italian Renaissance and the Hopi tribe in Arizona. Images and how they are transmitted were a fundamental part of that understanding, but there is nothing paradoxical in the fact that the specialism of the new director of the Warburg is the destruction of images. Iconoclasm, which we have been appalled to see burst out again today, is “testimony to what art actually means to people, from love and desire to hate, anger and resentment”, says David Freedberg. “The humanities cannot be isolated from politics and the public context,” he has believed ever since he left South Africa on his own, aged 18, for political reasons. And so he intends to apply the Warburg’s skills and approach to the burning issues of our time, beginning with the shocking brutality practised by Isil. “Our philological strengths are great, particularly in the area of Arabic philology, so one of my missions will be to make those skills relevant in these days of huge cultural clashes.”

This comes at the right moment. Paroles Armées: Comprendre et Combattre la Propagande Terroriste, published late last year, is a book that has shaken the French public because, in his detailed analysis of Isil’s language, Philippe-Joseph Salazar, a French professor of rhetoric, has revealed what their leader, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, really means and why we cannot possibly counteract his preaching until we take it seriously instead of mocking it.

In January 2016, the Warburg held a meeting entitled Contemporary Image Conflicts: Violence and Iconoclasm from Charlie Hebdo to Daesh [Isil], and Freedberg applied his knowledge of past iconoclasm in the West. He said, “The old conflation of the image and the living lies at the basis of Daesh’s iconoclasm and its awful reduction of its opponents—real or imagined—to the status of mere images.” The chanting soundtrack to the videos released in February 2015 of Isil destroying the sculptures in the Mosul museum is saying that the Prophet “has ordered us to obliterate and remove the sculptures”, “his companions did the same after him when they conquered countries” and “the monuments you see behind us are but statues and idols of the people from previous centuries, which they used to worship instead of God”. But the words go beyond these warped references to the hadith, the tradition attributed to Mohammed, said Freedberg, and so a new reason is added for what is being done: “These statues and idols were not here in the time of the Prophet or his companions; they have been excavated by Satanists.”

Iconoclasm is often accompanied by murder, and just as the destruction of images by the Protestants in Antwerp Cathedral in 1566 was followed by the killing, first of the priests, the guardians of those images, and then the Catholic community, the destruction at Palmyra was accompanied by the killing of the 82-year-old Syrian archaeologist Khaled al Asaad, who had worked on Palmyra all his life. “If you protected a picture you were aligned with the political and religious forces it betokened,” said Freedberg.

He went on to give physiological reasons for the revulsion we feel at seeing sculptures being attacked. “Every splitting open of a head in the Mosul video produces a shudder in the beholder’s body… every use of a pneumatic drill to erase a face or… put its thundering bit into the eyes of these images generates a visceral and interoceptive response… we feel the violent assaults and piercings of the bodies of others in our own bodies through the activation of our own somatosensory cortex, insula and other cortical correlates of sensory feeling”.

These comments, made possible by modern neurological discoveries, expand on Aby Warburg’s own intuitions. He had a great interest in movement in the Italian Renaissance, especially in the paintings of Botticelli, which culminated in his term the Pathos Formula, the idea that certain gestures have universal and perennial significance. This is the other strand of Warburg’s thought that needs reviving in the Institute, believes Freedberg. Scholars have been looking at gestures simply in terms of the attitude of a classical sculpture copied in a Mantegna, for example, to identify the afterlife of antiquity, but what they have forgotten is that one of the reasons these expressions of emotion have been transmitted over the centuries is not because one artist is copying another but because there are basic biological reasons for expressing oneself in a certain way. “You throw up your hands when you’re grieving or when you’re jumping for joy—those are a basic bodily needs,” says Freedberg. “Cognitive neuroscience has now given us the wherewithal to understand more about how people react to images, whether in museums or in private.” He hopes therefore to be able to appoint a neuroscientist to the academic staff, as well as an anthropologist or anthropologically inclined historian of art or music.

All in all, David Freedberg sees his role as reviving Aby Warburg’s influence, which, he believes, was diluted under the directorship of Sir Ernst Gombrich (from 1959 to 1976).

While acknowledging Gombrich’s fame and importance, Freedberg says, “The interesting thing about him is that he was very sceptical, as indeed his successors have been, of Warburg himself. There was the concern that occasionally Warburg was thrown off track by his mental illness, but there was another reason: Gombrich served with the British Monitoring Service during the war, listening in to the German broadcasts. I think he came to admire British positivism, which went along with his affection and admiration for Karl Popper, the great Viennese positivist philosopher, so he was sceptical about the imaginative and inductive leaps that Aby Warburg made, and the Institute acquired a positivist tone that reined in its potential. I’ve been concerned that, despite the opening up of the archives by the post-Gombrich directors, the potential of Warburg’s work has not been realised. I think the Institute has become very philological, very antiquarian.”

Freedberg is aware that he must carry his academics with him and he may face some opposition, so, like the monastic reformers, he harks back to the founder’s charism. “My three objectives for the Warburg are all implicit in Aby Warburg’s work,” he says. “Aside from a distinctive contribution to the history of art, we need to take the work in anthropological, biological and political directions. Above all, what Warburg was interested in was the engines that drive cultural transmission. That is what we have to look at; it is all the more important in our time.”

The Warburg Institute is savedIn November 2014, a High Court judgment that the original deed of gift in 1944 had to be respected and the University of London was responsible for the Warburg Institute’s upkeep, continuation and integrity ended a ten-year struggle that had threatened to see the merging of its famous library with other research libraries and the effective extinction of its distinctive character. In February 2015, a memorandum of understanding was signed between the Warburg and the university, in which they agreed to collaborate, and shortly afterwards, David Freedberg was appointed director, from Columbia University, where, in 2001, he founded the Humanities and Neuroscience Project at the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America, of which he is also director. The Warburg has now regained the support of Aby Warburg’s descendants, in particular, the banker Max Warburg, and Freedberg is launching a major fundraising campaign, the first in the institute’s history.