In just two years, London Craft Week (3-7 May) is on its way to becoming an unmissable date in the art and design diary—putting an emphasis on the array of craftsmanship that lies behind a wide range of items, from clothes to knives, from ceramics to candles.

Last year, there were 70 events staged across London. This year, there will be 129, featuring workshops, open studios and special displays. Crafts that visitors will be able to experience include perfume-making, diamond-cutting, porcelain-painting and silverworking.

The programme (supported by Vacheron Constantin and sponsors Grosvenor and Mulberry) embraces the luxury market, with brands such as Chanel, Lalique and Rolls-Royce joining in, and shops including Selfridges and Fortnum & Mason hosting events.

The Royal Opera House and the William Morris Gallery are among institutions opening their doors to show “The Making Behind Buildings”. The British Museum hosts displays of Chinese calligraphy, while fans of Game of Thrones can take a tour of costumier Angels.

At its heart, though, London Craft Week highlights the artistic brilliance and skill of 214 individual makers, from 17 countries. Five participants are interviewed here.

• For more, see www.londoncraftweek.com

Chris Keenan, potter Chris Keenan started out as actor, and while he was with a touring company in Sheffield, he met the potter Edmund de Waal. Later, after landing one day’s work in an entire year, he resolved to change direction and wrote to De Waal, asking to be taken on as an apprentice.

Twenty years later, and now aged 56, he says he has never regretted that decision. “The tangibility of my work is hugely important to me. I came from something—acting—that was very ephemeral, to something very material and actual, and that was fantastic,” he says.

He has always worked in porcelain, using just two Oriental glazes, celadon (which is pale blue to olive green) and the dark, glassy tenmoku. “That very limited palette has not limited what I can do with them,” he says. Despite their appeal to collectors, with many having followed his career, all his pieces are made to be used. “Everything I create will do a job if you want it to. Function can be just something beautiful sitting on a shelf, but I want things to do the best job they possibly can.”

However, Keenan also makes what he calls “extracurricular work”—objects of pure beauty, which ask people to play with them to realise their meaning. He is currently filling Blackwell House in the Lake District with a commission that amounts to an installation of pottery. “I see myself as a craftsman plus,” he says. “This is what I do to make a living. But my prices aren’t art prices—I haven’t made that leap that happens when something is defined as art.”

• Prices: from £30 for an espresso cup to £2,500 for A Bode of Stones, one of the extracurricular works. Where to buy: contact via his website (www.chriskeenan.co.uk); at fairs, open studios and exhibitions; or via London Contemporary Ceramics Centre (www.cpaceramics.com) or Contemporary Applied Arts (www.caa.org.uk)

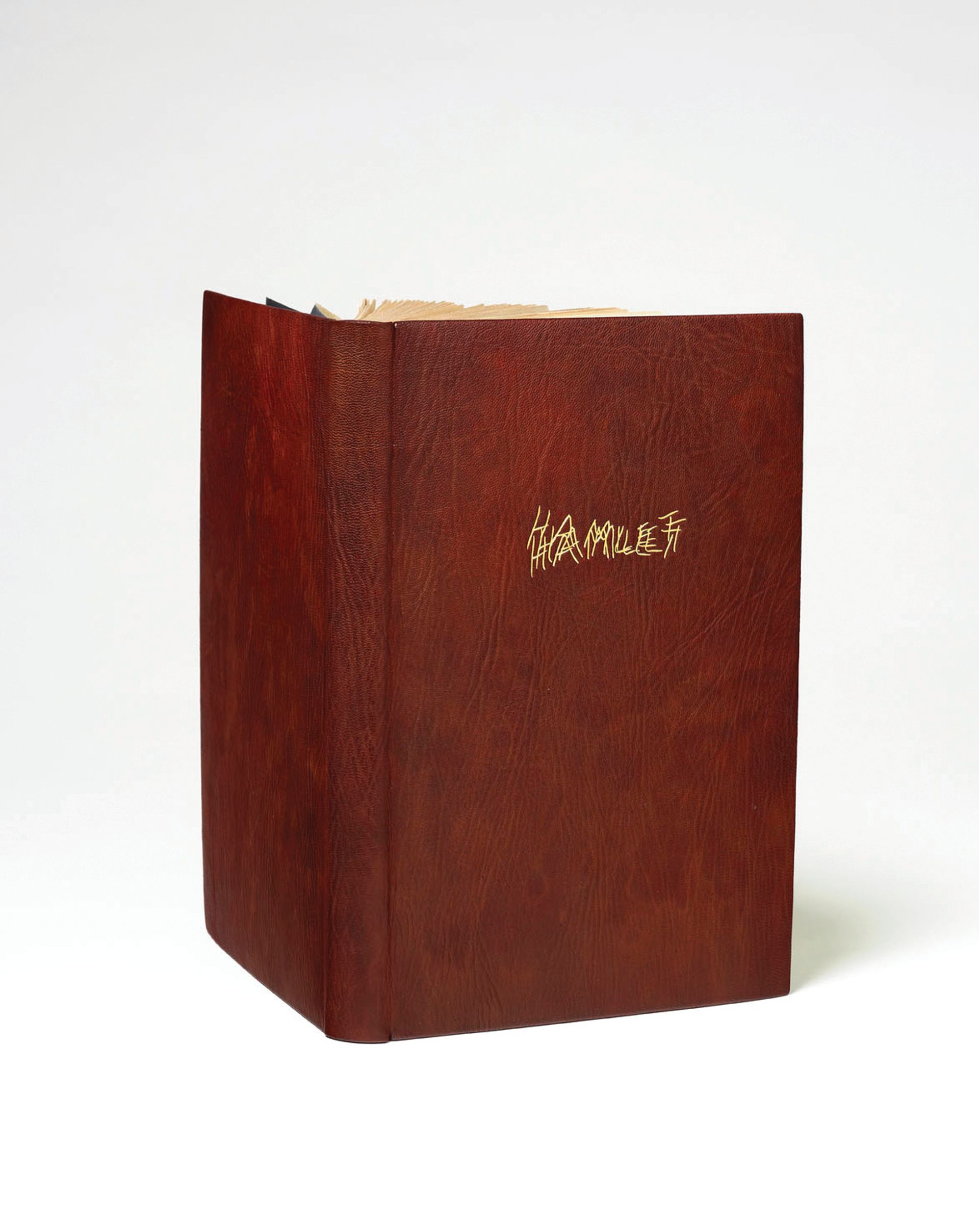

Tracey Rowledge, bookbinder “Like most people who are bookbinders, it was not my first career choice because it is reasonably obscure,” says Tracey Rowledge. It was when she found herself at a loose end after a fine art degree at Goldsmiths, University of London, that she discovered her calling almost by chance. “I felt that it could be a way for me to climb back into my creativity. I thought I could make a living as a bookbinder to support making art. In the end, the bookbinding just took over.”

She had always been interested in the craftsmanship of things, and loved the minutiae of the exacting engineering that bookbinding requires. A two-year diploma course gave her the rudiments, and a Crafts Council grant helped her to set up as a self-employed bookbinder. But she has continued to learn and extend her skills.

Her work now has the delicacy of drawing, with finely tooled gestural lines in gold a speciality. But the 46-year-old works across a broad range, from commissioned book bindings, to restoration, to drawings and panels that are pure art. She is also a founding member of an international bookbinding group called Tomorrow’s Past, which rebinds antiquarian books in need of repair. “We’re creating conservation bindings that are structural and creative responses to the book.”

Her work sells mainly to people who collect books, but its variety means it is hard to pin down. Rowledge doesn’t see a boundary between bookbinding and her other artistic endeavours; one thing tends to lead to another. “I call myself an artist because it’s an umbrella term. It’s easier to digest the breadth of what I do, rather than saying ‘I’m a bookbinder’, but for a lot of the time I’m not working on books.”

• Prices: from £500 to £5,000. Where to buy: contact via her website (www.traceyrowledge.co.uk), or Contemporary Applied Arts (www.caa.org.uk)

Jo Hayes Ward, jeweller Having completed a degree in metalworking and silversmithing at Camberwell College of Art in London, Jo Hayes Ward looked around for what she might do next. Jewellery-making seemed an obvious career. “It was a mixture of really wanting to make things, and having to have a sustainable business,” she explains.

By 2006, she had pursued that instinct by working with three jewellers and taking an MA in goldsmithing, silversmithing, metalwork and jewellery with the Royal College of Art. She was ready to launch her own business.

Her work, she says, conforms to “quite a specific aesthetic”, using building blocks of precious metals to create intricate and sculptural pieces. “Some of them are very structural, so they have lots of negative space, and some are much more pattern-based. It’s all very tiny.”

Everything is designed using computer programmes, then 3D-printed into wax models, which are cast directly into metal. Now 37, Hayes Ward found that her business took off when she moved away from the craft world into fashion and design. “I’d describe myself as a fine jeweller,” she says. “I fit into the craft world as well as the design world. But the craft scene in the UK is very small and has a very specific amount of money that people are going to spend on you, so I have had to expand out of it into a more high-end market.”

Despite this, she adds: “I think craft has become more in vogue in the past five years. It is not a dirty word any-more—before it was just old ladies knitting. I think people are beginning to appreciate hand-made, and desiring it more, and are willing to pay for it.

“It irks me a bit to be pigeonholed into any one area. It’s a holistic thing. To be a designer or a craftsperson, it is all part of the same thing—a creative business.”

• Prices: from around £700 for a silver ring, to £15,000 for a bespoke piece. Where to buy: contact via her website (www.johayesward.com). Also selling through stores worldwide, from Paris to South Korea, including Dover Street Market in London and New York

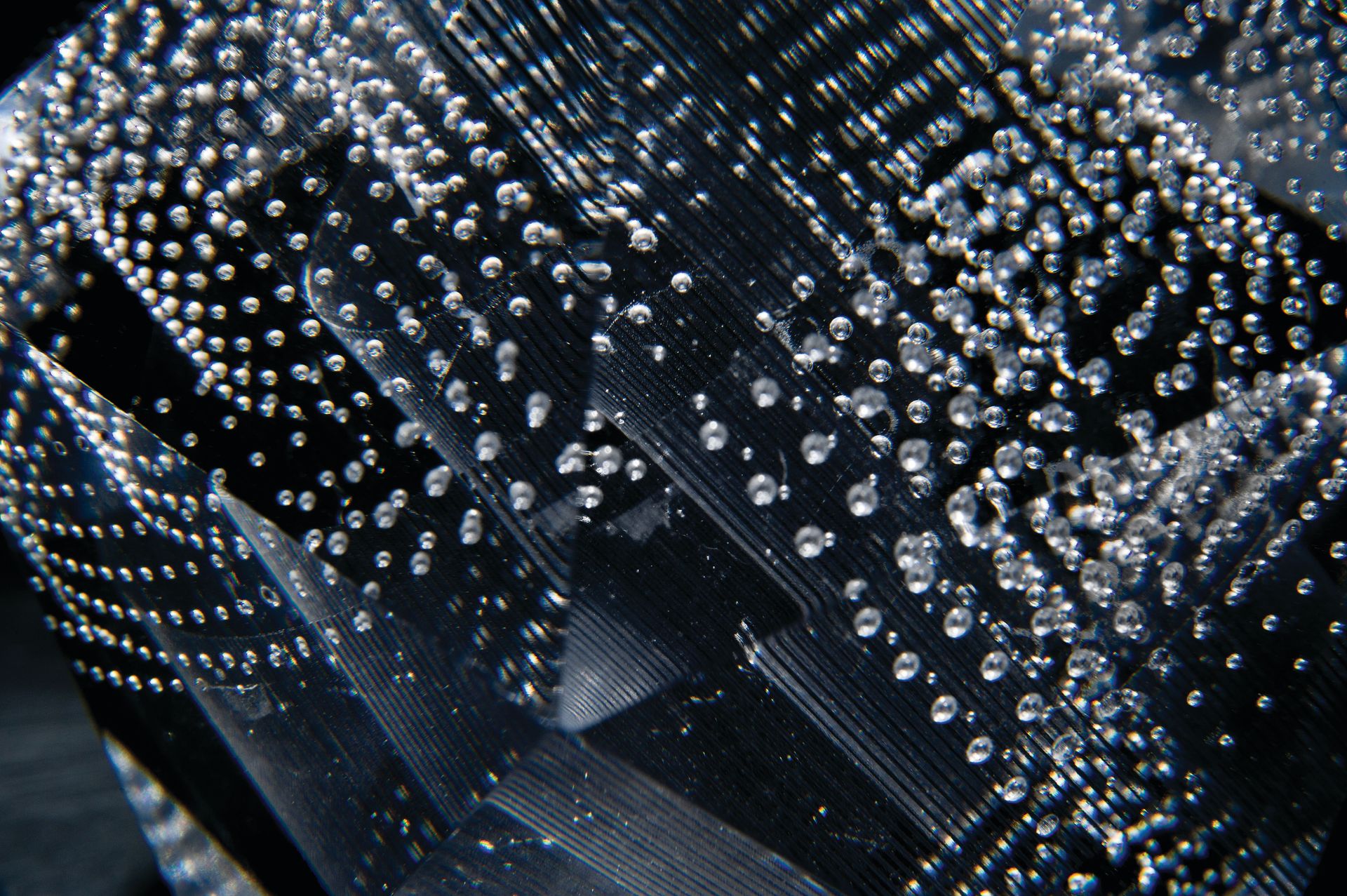

Shelley James, artist working in glass A serious road accident when she was knocked off her bike proved the turning point in Shelley James’s career. She had previously trained in textiles in Paris, and then worked in corporate branding, becoming a specialist in internal communications. “I was looking at the way the outside of the organisation and the inside fit together, and that led to questions of identity and looking in and out,” she says.

A printmaking course in Bristol followed, and she adapted the techniques for working in glass. “What I was trying to achieve was the conversation between internal and external space, between how things feel on the inside and look on the outside.” But it was the scans of her head injury, which she printed on glass, that intrigued her physicians and led to a residency at the Bristol Eye Hospital, where she worked with staff and patients to use glass “to open a conversation about clinical phenomenon”.

From these beginnings and a PhD at the Royal College of Art, she has evolved an extraordinary set of collaborations with scientists, using glass that is carved, cast, cut and shaped to make work that is aesthetically beautiful and yet also responds to what they are discovering about vision, illusion and space.

One of her current projects is with the mathematician Roger Penrose on a new generation of mathematical models. Her common ground with the scientists is in “a kind of inquiry, which means we each have a research process where we are asking a question and finding ways of answering that question. By building these objects you add an expressive or poetic dimension, but then the scientists find that the material itself illustrates the kind of principles they are thinking about.”

The specialised nature of the 52-year-old’s work means her pieces are mainly bought by museums, or the collaborators who commissioned them. But some are available for sale. “Each takes a long time to make,” she says. “I take great care that the objects are as beautifully finished as I can make them.”

• Prices: from £150 to £5,000. Where to buy: contact via her website (www.shelleyjames.co.uk) and at open studios. Also represented by Sarah Myerscough

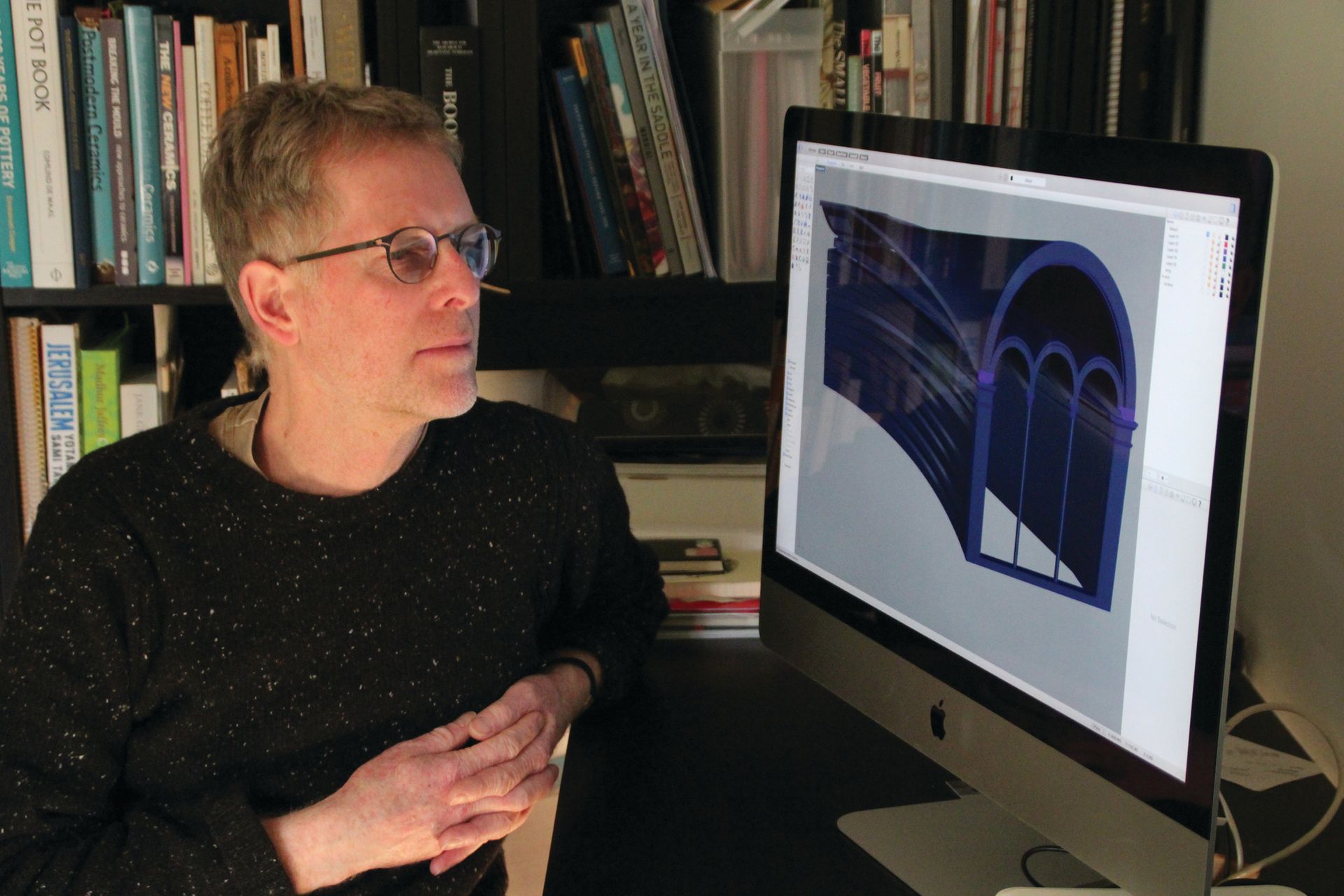

Michael Eden, maker His website describes him simply as a maker, but Michael Eden sees his non-functional 3D-printed creations as works of art. His starting point is to take historical ceramic pieces—such as 18th-century Sèvres porcelain—and, in his words, “bring it kicking and screaming into the 21st century”. He adds: “I’m exploring themes of the cultural and financial value of objects, and exploring craft and making, new tools and technology.”

Based in Cumbria, Eden spent 25 years making functional pots, supplying shops such as Habitat, but, almost on a whim, decided to learn to code in order to understand websites. He became intrigued by the contrast between soft, malleable clay and the hard-edged, fixed world of coding, and started to investigate 3D-printing techniques. “I thought if I can draw these things on a computer, then I can make anything,” he says. “I am completely free to make the impossible object.”

In order to develop his ideas, he took an MPhil at the Royal College of Art. His final creation as part of that process was the Wedgwoodn’t Tureen, designed both as a tribute to Josiah Wedgwood, a great British pioneer of pottery manufacturing and a leader of the Industrial Revolution, and as a means of highlighting the new industrial revolution that some people believe 3D-printing represents.

This shift from what might once have been defined as craft to what is more easily called art, means that pieces by 60-year-old Eden are represented in a growing number of museums and galleries. But he is reluctant to place a label on his work. “We live in a time where such titles are becoming very slippery,” he says. “I’m happy to be working in some sort of grey area between art and design, and craft and technology. It gives me complete freedom to go where I want.”

• Prices: from about £3,500 to £16,000. Where to buy: works can be seen on his website (www.michael-eden.com). Represented by Adrian Sassoon, London