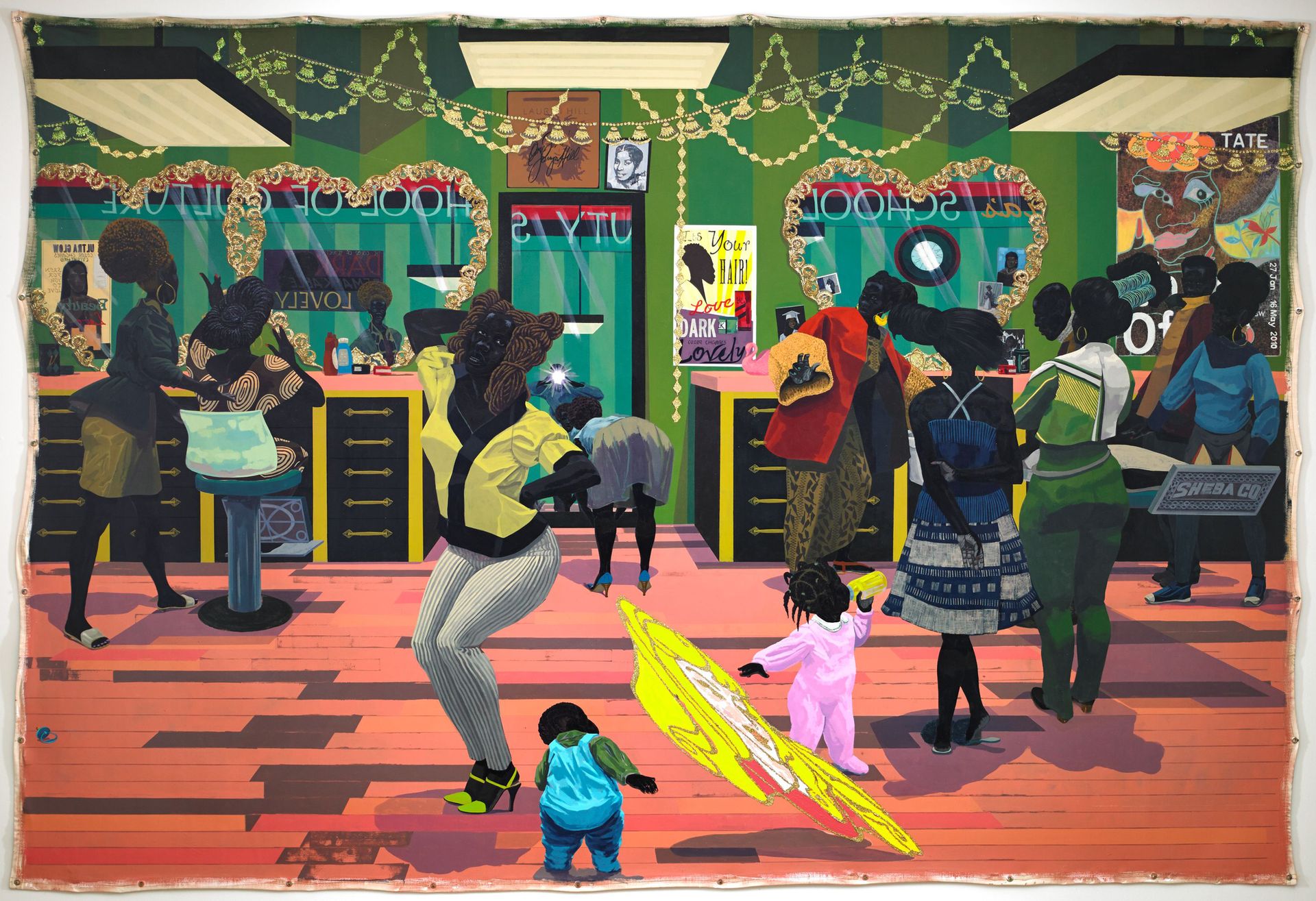

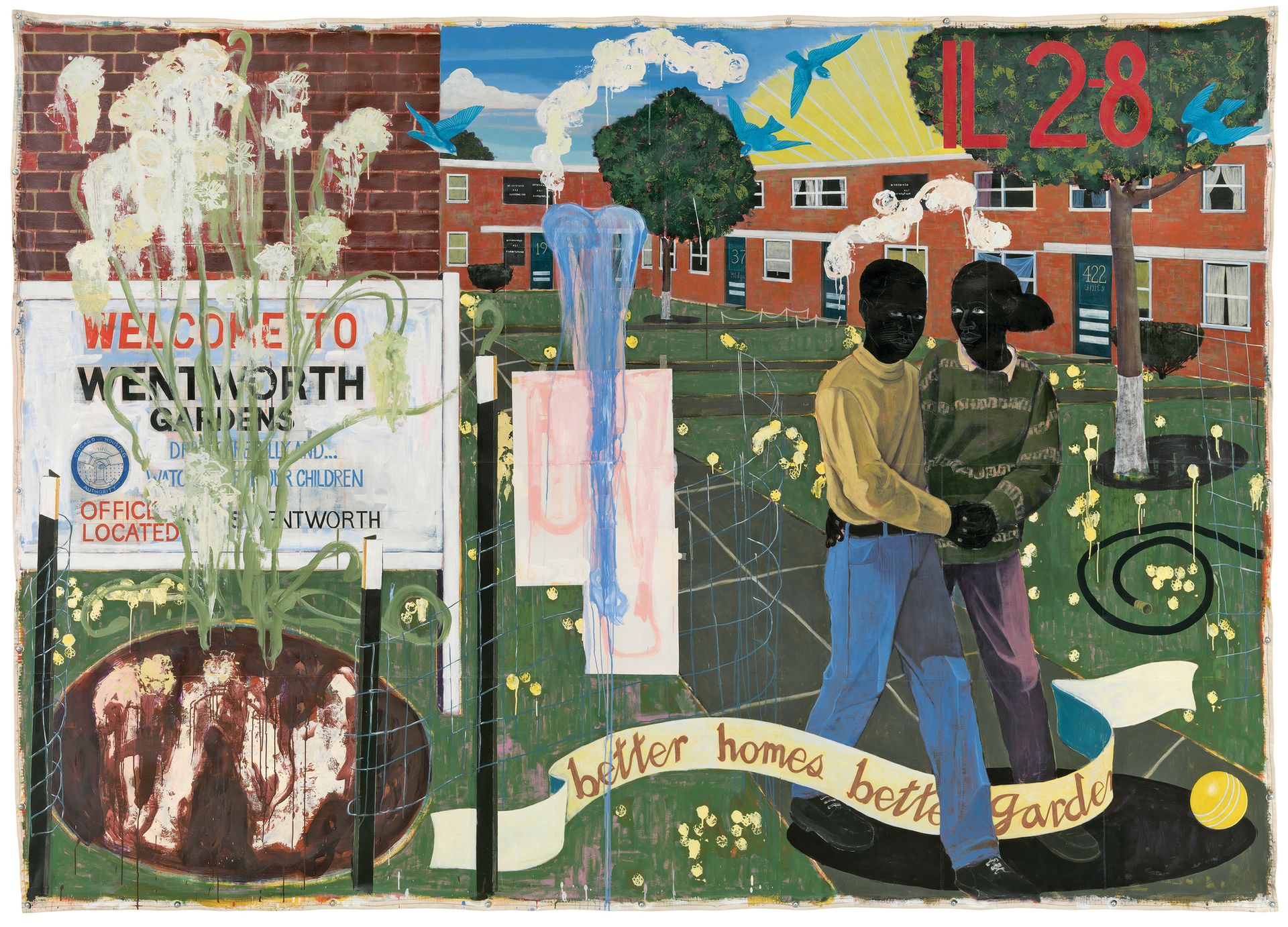

Kerry James Marshall has worked for the past 35 years with a singular goal in mind: to place the black figure squarely at the centre of the art canon. He has made much headway, as can be seen in his first major painting retrospective, which opened last month at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago and will then travel to the Met Breuer in New York and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (LA MoCA).

His classically composed pictures are filled exclusively with black subjects, settings, cultural references and artistic allusions, from African sculpture to urban street slang. Introducing powerful images of people of colour into museum galleries normally dominated by European art history, Marshall’s work also resonates with a more diverse community than is usually seen in the white upper echelons of the art world.

The Art Newspaper: Have you been involved in the selection of the works?

Kerry James Marshall: When the show was first proposed, the way Helen Molesworth [chief curator at LA MoCA] put it was: “Are you ready to submit?” If you’re going to have a curator who’s going to do a proper survey, then the curator has to curate. You don’t get to pick the show. The thing is, it’s hard to let somebody else curate a show of your work. Retrospectives are an odd kind of animal.

Right—it’s supposed to be the artist looking back on their career.

But then I would be picking. There are a lot of factors that determine what the shape and scale of a show would be. And the reality is that retrospective shows are kind of a political reckoning as well. You might have collections that have more than one work of yours, and maybe they’ve got four or five things that you really like. But they’re not going to put four or five things from one [collection in the show]. Some institutions won’t lend. At first, Lacma [the Los Angeles County Museum of Art] refused to lend De Style (1993). But now it’s in.

That would have been a big hole. That was your first institutional acquisition, wasn’t it?

Right. So you have to wrestle with these funny things that sometimes you take for granted.

I saw the checklist [the curatorial team] put together. They went on a road trip, kind of to get a look at things in person. I didn’t have any real input into the selection except, towards the end, I said: “I’ve got at least three must-haves.”

What were those?

One of them was the girl on the blanket on the yard [Untitled (Beach Towel), 2014]. As a painter, every time I make a body of work, I’m trying to make it better than the last. That painting, I think, is one of the best paintings I’ve ever made. Another was Vignette (Wishing Well) [from 2010]. And the other was a Lost Boys. I said, “I’ve got to have some of this.”

In New York, you’ll also select works from the Met’s collection to be installed in the Breuer building. How will that work?

We haven’t quite figured it out but it’s the same kind of process [as selecting works for the original exhibition]. There’s about 40% of what you want that you’re able to get. Even though the Met Breuer is an extension of the Met, each department is highly protective of the things in their domain. And museums have contracts with donors that govern the way things can be used or moved or how long they can be sent out. I walked around the museum a couple of times with Ian Alteveer, who’s a curator at the Met. It was like being in a candy store.

So would you like to have the Met’s collection side by side with your own works?

Maybe not so much that you draw direct comparisons but it would be nice to have clusters of things from the Met collection stationed at different places [in the exhibition] so there is a constant return to art history. Then you put people in a frame of mind where you’re oscillating back and forth between things. That’s how I would like to do it because if you isolate the classical works, then it’s like doing two shows. On some level, what’s the point?

In a letter to young artists in the exhibition catalogue, you write: “No one with small ambitions and vague goals ever amounted to much in this game.” Why is that important for an artist?

I think the drive is everything. Because the way I see it, you have two choices: one is that you can feel like you’re driving your position, or you accept that somebody else is driving and you’re simply waiting around for somebody to pick you up. You can’t afford to do that.

Your work doesn’t often come to auction. Is that a deliberate choice?

There’s almost nothing you can do about that. One way of staying a little out of that is to focus on institutional collections first, so you’re not just in the kind of cruel exchange market. But the reality is it costs a lot to [be an artist]. Not only to have a place to do it but to keep buying material and then to have the resources you need to explore. You’ve got to make some money. It’s true. And the art market is out of control and completely irrational and overheated on some levels because there’s a lot of money sloshing around. And if the difference between being able to have some of it or not is that you might have to make more work than you feel comfortable doing—you’ve got to work harder. If you’ve got to work seven days a week, as opposed to taking off a few days, so that you can have something to send to your gallery when they go to an art fair, it makes sense to me to work seven days a week.

Because in the long run, the market on some level determines the value of an artist’s production. If you think you don’t want your work to be traded in those kinds of ways, that’s like saying, I would rather be a sharecropper for the rest of my life, just making enough to get by, as opposed to somebody who has the capacity to produce at your maximum ability—even if sometimes it means you’ve got to work overnight and work every day and not take any vacations…

It’s been work for me to arrive at the moment that I have. Everyone wants to feel like they are equal to those operating at the highest level. And if that means that the work starts to command a price that’s way beyond anything you yourself can even afford, you’re better off trying to be in it at that level than not. When the work started to sell at those kinds of prices, I didn’t get scared. I got busier. My goal was always to be in a museum.

Do you feel like you achieved that goal? All those dreams you had as a young man…

I got every one of them. It may not mean anything to a lot of people but I’m not so jaded. And I’m hyper self-conscious about the way I operate in the art world. I got a request for reproduction rights from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They want to put that studio painting [Untitled (Studio), 2014] in their masterworks publication. I’m not too big or proud to say that meant something to me. I have a work that’s in the first show at the Met Breuer, Unfinished [until 4 September]. So now I’m in a show with Leonardo da Vinci. This is why I came into the art world.

• Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (until 25 September), the Met Breuer, New York (25 October-29 January 2017), and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (26 February-25 June 2017)