Throughout the Early Modern period (from around the late 15th through the late 18th centuries), monarchs and lesser rulers built and decorated their palaces with an intention to impress others with their wealth, power and taste. For the past 30 years much art-historical research has gone into these collections and those who gathered them, but recently, perhaps under pressure of literary interest in “reader-response”, historians have turned their attention to the nature of and intentions behind display, and to viewers’ reception of works on the walls.

One new angle has been an examination of 17th- and 18th-century specialist publications of art collections. The generic term for this is Galeriewerke, or gallery works, a substrate of the history of the book. Princely Splendour: the Power of Pomp at the Winter Palace of the Belvedere museum complex displays in the enfilade of its recently restored Rococo rooms many examples of Galeriewerke from the middle of the 17th to the end of 18th centuries, along with some of the paintings and sculpture illustrated in them.

The initial impulse for Galeriewerke was an extension of the need to show off, but as works of art were largely immobile, print offered an alternative. The Habsburg Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, the Governor of the Spanish Netherlands (1647-56), amassed a huge art collection and commissioned David Teniers the Younger to create in 1653 the first “collector and his collection” painting. This and other paintings like it give us a clue as to the nature of princely “hangs” in the Baroque era. The first room of the exhibition is arranged to suggest the randomness of late 17th-century display.

It was Archduke Leopold and David Teniers who invented the Galeriewerk with the publication in 1660 of Theatrum Pictorium, a collection of prints of the “best” works in Leopold’s collection. The Winter Palace exhibition includes Teniers’s small oil copies of the works, from which engravers made plates for the book’s 243 mainly 16th-century Venetian paintings. (The paintings themselves were bought by Leopold from the estate of the Duke of Hamilton, who died in the English Civil War.) The Theatrum was published in Latin, Dutch, French and Spanish—interestingly not in German—with a clear eye to pan-European audiences, who seem to have been suitably impressed as the book went through five editions up to 1755. As was the case with books until the 19th century, the bindings of the Theatrum were custom made: limited, gift editions had exquisitely stamped calf leather spines and covers, with gold tooling, including the arms of the owner or donor.

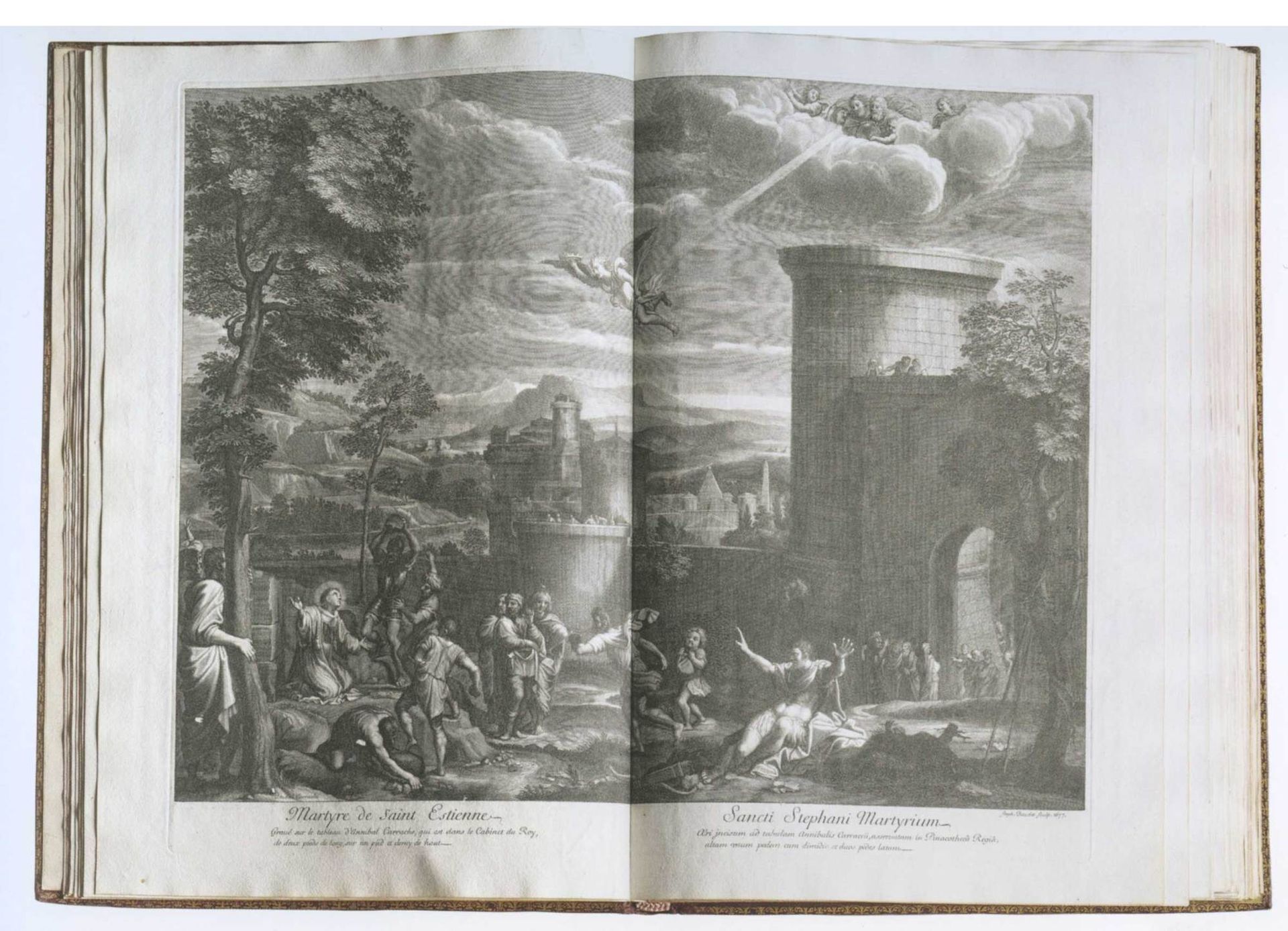

Never to be surpassed, Louis XIV caused his finance minister and secretary of state, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to make a royal Galeriewerk, but, of course, on a far grander scale than that of his Hapsburg near neighbour. The first volume of the Tableaux du Cabinet du Roy appeared in 1677 followed by ten more, the plates depicting all “departments” of the royal collection: medals and medallions, sculptures, both ancient and modern, the grotto at Versailles, and pictures of the various royal palaces and gardens. Included as well were paintings: for example, Annibale Carracci’s The Stoning of Stephen (1683) in the Louvre palace, which, with its double-page spread, is typical of the lavish treatment allotted to the works in the Tableaux. The initial print run was for Louis’s own disposal, but in 1679 Colbert made the books available to the public supposedly to demonstrate the King’s generosity and the growth of the arts in France. The Tableaux, like many of the Galeriewerke, was a publishing failure as the production costs far exceeded sales.

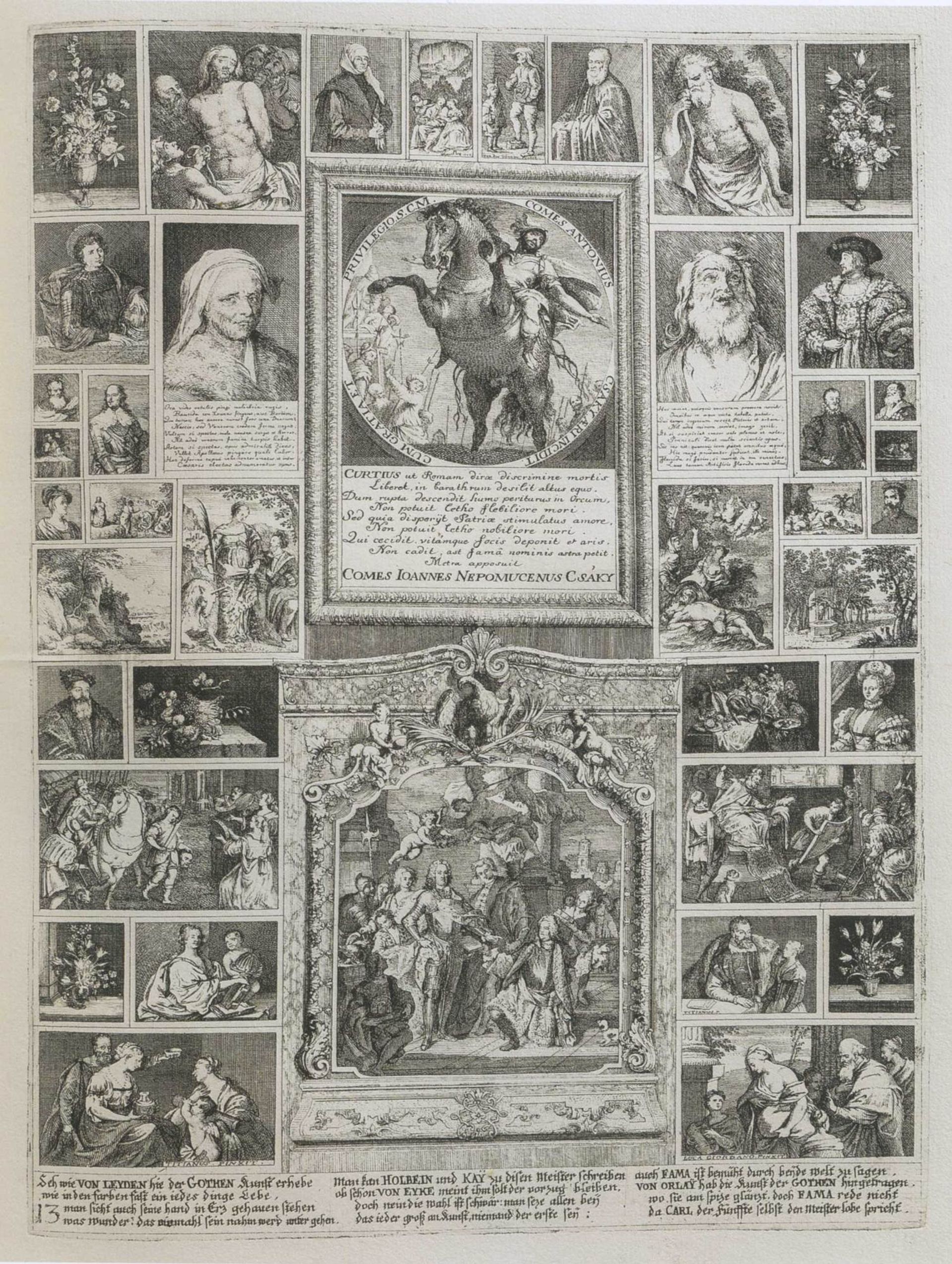

As in other spheres, debt and cost never deterred princes from competing with one another. The Emperor Charles VI also intended to publish a 30-volume Galeriewerk of the Habsburg art collection. The imperial holdings (including those in Archduke Leopold’s collection) were gathered up and assembled in 1728 in the Stallburg, the former stables of the Vienna palace, arranged in the Baroque manner. The publishing project was never completed, but the Prodromus, a kind of preview of what might have been, was compiled in 1735: miniature tableaux synoptically displayed more than 1,000 paintings.

Other nobles also published—the Earls of Derby at Knowsley Hall (1729), Augustus II/III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland(1753-57) and Frederick II, King of Prussia (1764)—to greater or lesser degrees, depending on the extent of their collections.

Pomp rationalised

In 1776 the Habsburg collection was moved from the Stallburg to the suburban Belvedere palace, theatrically and ahistorically depicted in an allegory by Vincenz Fischer to give maximum credit to the Enlightened emperor, Joseph II, as the mastermind of the plan (and to whom due credit should be given). The display of paintings in the Winter Palace is one the earliest examples of what we know as a typical museum display, with paintings arranged discretely in galleries by artist or nation.

The embourgeoisement of the Belvedere was furthered by its partial opening to the public in 1781 and the publication (1783) of a descriptive catalogue of the works by Christian von Mechel, a Swiss engraver, publisher and art dealer specifically employed by the emperor to organise the collection. That publication, in which the text begins to take precedent over the image, was more a vademecum than a Galeriewerk, and was therefore the seed of today’s museum catalogue.

Pomp popularised

Originally, the elite who might see such art were few. But as the growing middle class became interested in and better informed about art, princes opened their collections to view. Towards the end of the 18th century, this was accompanied by the publication of the first printed guides to local collections. On display at the Winter Palace are those to various princely palace collections in Pommersfelden (1774), Schleissheim (1775), Salzdahlum (1776), Düsseldorf (1781), Kassel (1783), Schwerin (1792), and further afield, the Uffizi (1778), the Palais Royale, Paris (1786), and Houghton Hall (1788). Now the wheel has made a full turn: where the Galeriewerk initially aimed to impress those who would never see the works in situ, now the book tells the viewer on the spot what she is seeing.

For anyone interested in the history of illustrated books and catalogues, this show should not be missed.

Pomp and the populace

Princely display in the Early Modern and Baroque eras frequently came in the form of banqueting. At the Kunsthistorisches Museum, the exhibition Celebration! shows 125 items, thematically arranged, to give the visitor some idea of what these feasts and festivities looked like. The show includes paintings, prints, drawings, furniture, musical instruments, and tableware (including ingenious and exquisitely worked “table toys” made to look like ships, cannons and other automata) and—not least—a magnificent, entirely intact, 56 ft-long, 6 ft-wide linen table cloth woven in 1527 at the command of the Emperor Charles V for use at the chapter meetings of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Woven into the tablecloth are panels of the coats of arms of the knights and the order’s patron saints. First used in 1531 at Tournai, numerous subsequent paintings and illuminations feature it. Other galleries show elaborate firework displays, arms and armour for jousts and tourneys (there is also a video of a joust, to give one some sense of what it was like), and a display of items showing “the people’s” celebrations, which notably includes works from the museum’s extensive Brueghel collection.

The occasion for this exhibition is the 125th anniversary of the opening of the Gottfried Semper-designed museum building to the public on a permanent basis to view the Habsburg collections. The exhibition of one object for each year of the museum’s existence is sponsored by Uniqa and the Österreichische Lotterien.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of this exhibition is that the extraordinary exhibits are drawn almost entirely from the KHM’s own holdings—and they are only the tip of the iceberg. A feast beyond imagining.

Donald Lee is the literary editor of The Art Newspaper.

Princely Splendour: the Power of Pomp, Winter Palace of the Belvedere, Vienna, until 26 June

Celebration!, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, until 11 September