Hilma af Klint: Painting the Unseen, Serpentine Gallery, London (until 15 May)

Yes, she was making abstract paintings before all the big (male) names of 20th- century Modernism—having been “instructed” during a séance by a spirit guide in 1904—but it is the quality and originality of her work that makes the reclusive spiritualist Hilma af Klint so much more than just a rediscovered artistic curio. (In any case, her academic training and career as portrait painter and botanical artist confirm that she was no outsider artist.) These exuberant, original and also oddly unsettling paintings are not to be missed, especially those from her monumental 1907 ‘Ten Largest’ series; these fill the Serpentine’s rotunda gallery with giant, 3m-high works evoking the four ages of man in floating and at times almost trippily hallucinogenic flower forms, but always underpinned by a decidedly disquieting and highly subjective intensity. Time to rewrite the history books…

The Peculiar People, Focal Point Gallery, Southend-on-Sea (until 2 July)

It may be a little dense and tricky to navigate in places (more labels, please!) but this is nonetheless an important and timely show which presents a very different Essex from the bling and vajazzle of popular lore. For alongside its reputation for flashy gangster/celeb retreats and the UK’s first out-of-town-shopping mall, this much-maligned county also boasts an impressive counter-culture track record, highlighted here by artworks and extensive archive material related to the rich history of radical communal living experiments from the 19th century onwards. These range from pioneering industrial worker estates and garden cities to anarcho-naturist colonies, all augmented by prints and ephemera from such illustrious Essex inhabitants as Eduardo Paolozzi, Nigel Henderson and Henri Chopin, and significant visitors including the architect Cedric Price, whose (tragically unrealised) pneumatic roof for Southend’s High Street would have been one of the wonders of the south-east coast.

Sharon Hayes: in My Little Corner of the World, Anyone Would Love You, Studio Voltaire, London (until 5 June)

The UK’s first solo show of this important US artist takes the form of a major new commission at Studio Voltaire, a space renowned for punching above its weight and letting artists go full throttle. Hayes is widely known for patrolling the territory between the personal and the political, and in this new five-channel film she re-presents material extracted from queer and feminist archives in the US and UK, dating from the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s. But there’s nothing dry or doctrinaire about these at times moving, sometimes shocking, and on occasions deeply depressing texts, which are read aloud by 13 members of the contemporary LGBT community in Philadelphia in the intimate domestic spaces of a real house. At the same time, the wider and more publicly political application of their words are also flagged up; the films are projected onto a hoarding-like plywood structure, which on its other side is a literal noticeboard, fly-posted with literature from these ground-breaking organisations.

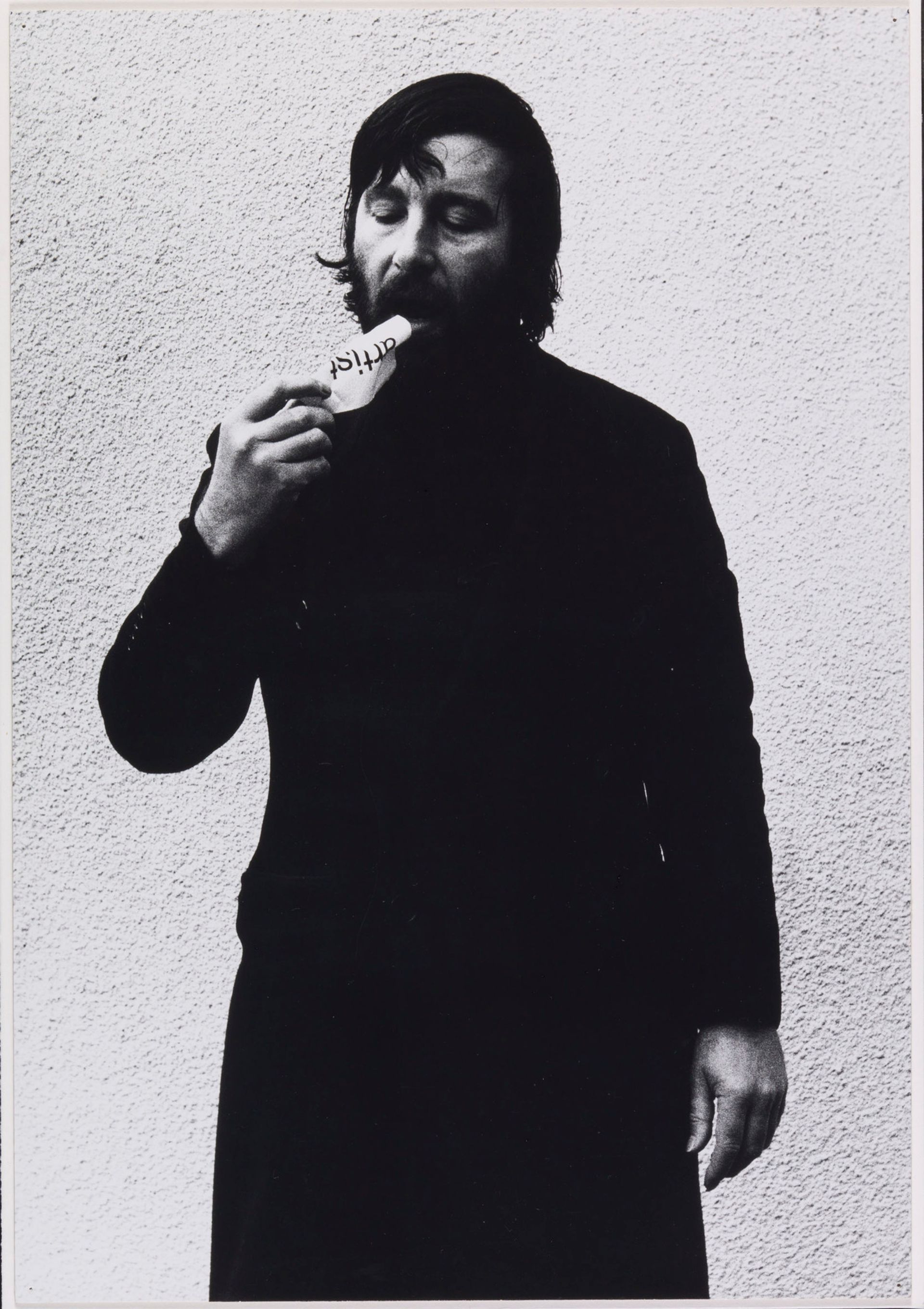

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979, Tate Britain, London (until 29 August)

This is an important, rigorous and lucidly curated exhibition, which firmly locates the UK within the global networks of international conceptual art and also reveals the strength of the Tate’s conceptual art collection. Whether Sol Lewitt’s triangulation of key London sites Lisson, Tate and Nigel Greenwood Gallery; South African artist and Central St Martin’s tutor Roelof Louw’s pyramid of take-away oranges; Stephen Willats’s rigorous socio-political-aesthetic exploration of life in a London towerblock; or the artistic perambulations of Richard Long and Hamish Fulton, there’s an invigorating scope to these challenges to what art could or should be (with many welcome dashes of humour amid the chin-stroking).

Spanning Harold Wilson’s 1964 Labour government to Margaret Thatcher’s premiership in 1979, the show also reflects a period of immense social and political change, which plays out through many of its exhibits. This culminates in a terrific final room of work from the 1970s by the likes of Mary Kelly, Victor Burgin and Margaret Harrison, all variously made in the belief that art could and should engage with the often uncomfortable realities of daily life. In an exhibition of this nature, where idea takes precedence over object and where the original artworks were often immaterial, ephemeral and existed only in the moment, a reliance on archival documentation and a measure of vitrine gazing is inevitable – but gaze hard and the rewards are great.