Zaha Hadid, who died suddenly in March aged 65, transformed our ideas of what architecture might be. The first woman to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize was born in Baghdad in 1950, moving to London in the early 1970s to pursue her architectural education. Hadid first made her name not by actually building but with paintings of her ideas. Her series of large, black-ground paintings won her the 1983 competition for The Peak Leisure Club in Hong Kong. The cantilevered, dynamic forms she depicted were influenced by Russian Suprematism and Constructivism. They looked unbuildable, and probably were, given the limits of digital design at the time. This and many of her subsequent projects meant that for more than a decade Hadid seemed destined to remain a “paper architect”.

Of the few early schemes that did get built, the 1993 fire station at the Vitra furniture company’s Weil am Rhein factory near Basel is a gem. A tiny lightning bolt of a building in concrete, it traced the movements of the fire engines like choreographic diagrams—one of her canvases made architectural flesh.

Bigger commissions eluded her. As a Middle Eastern woman she was treated as an outsider by the stodgy architectural establishment. Her fans, however, recognised a visionary when they saw one. Fellow architect and former collaborator Rem Koolhaas described her at the time as “a planet in her own inimitable orbit”.

Hadid’s work evolved alongside the enabling software, from shattered tectonics to the complex curves of parametric architecture. By the mid 1990s, commissions came in from across the globe to Zaha Hadid Architects, the firm she founded in 1979. However, as her complex buildings emerged from the ground, criticism of her design approach, as expensive, obtusely inefficient and not always well finished, mounted. This was the price, maybe, of inventing a new architectural language. Less forgivably, she also demonstrated a cavalier approach to urban contexts and a willingness to work on overseas projects for dictatorial regimes. Historic quarters have been razed to make room for her strata and parabolas.

In this she is caught up in a wider reaction to the digitally derived forms that a new generation of architects now find overly egotistical, too random, and the product of a jet-setting clique of global architects who don’t invest enough time investigating the local.

Unlike her fading deconstructivist contemporaries, she remained a visionary, even if that vision was sometimes flawed.

Some of the architect’s landmark cultural projects—built and unbuilt

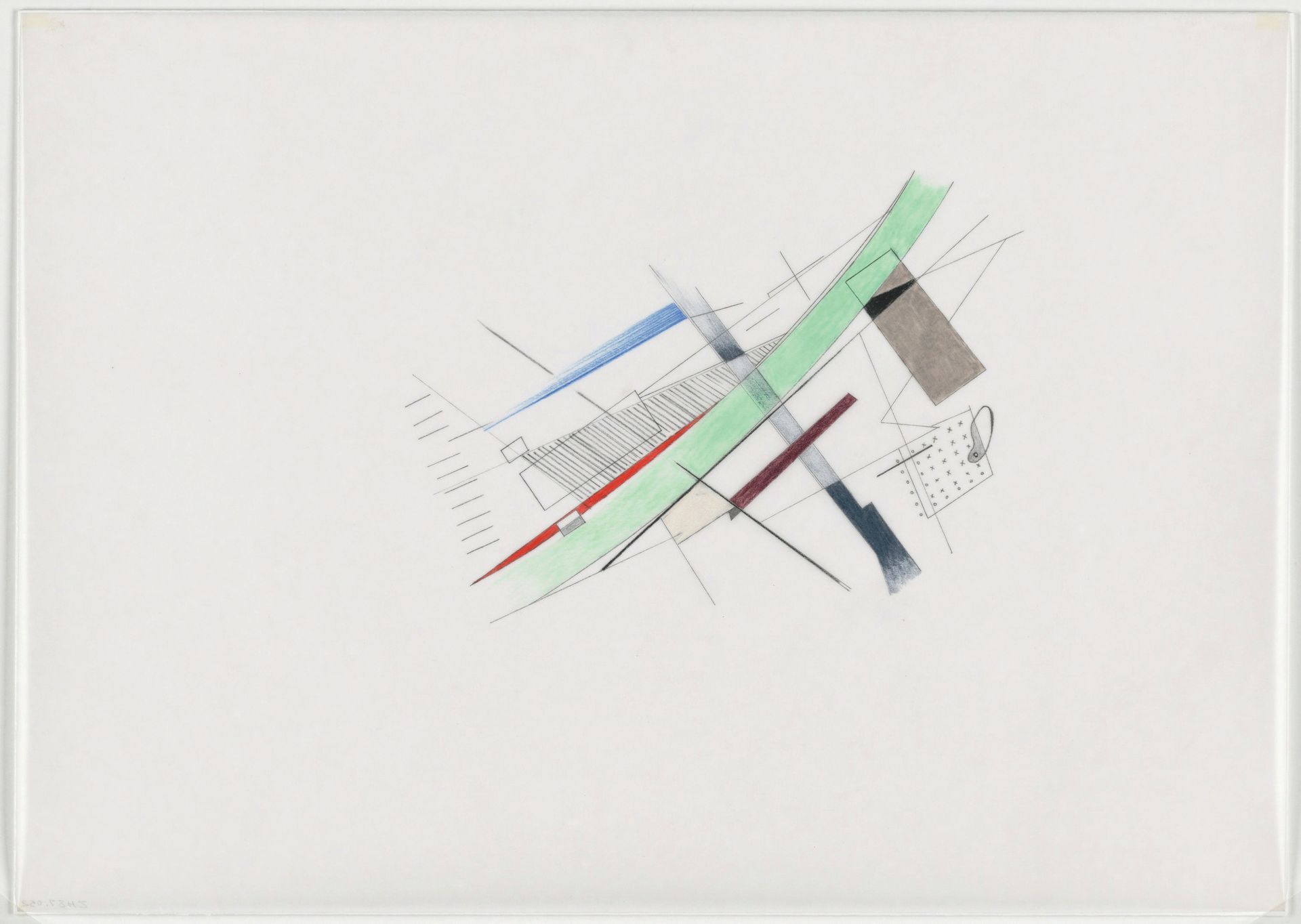

Parc de la Villette, Paris (1982-83)

Hadid lost out to Bernard Tschumi in the competition to turn a Parisian abattoir into a park and cultural venue, but her submission drawings are now in the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The shard sketches demonstrate Hadid’s fascination with early Modernist Russian art and depict stacked, uninterrupted planes that entwine with the landscape to form mobile gardens and structures.

Cardiff Bay Opera House (1994-96)

A competition-winning design for an opera house for Cardiff, conceived of as a “crystal necklace”, was scrapped after the Millennium Commission gave into pressure from local burghers suspicious of its avant-garde approach and buildability. The episode cemented Hadid’s reputation as risky and her refusal to take it lying down helped pin her with the “diva” label.

Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art, Cincinnati (1997-2003)

The first US art museum built by a woman was dubbed “the most important American building to be completed since the end of the Cold War” by the New York Times. Hadid’s expansiveness was here contained within a rectangularity demanded by the constrained site.

Zaragoza Bridge Pavilion (2005-08)

The hybrid bridge-exhibition space for an expo site in the northern Spanish city of Zaragoza was judged a great success. It also has an affinity with the infrastructure projects of the Spanish architect-engineer Santiago Calatrava.

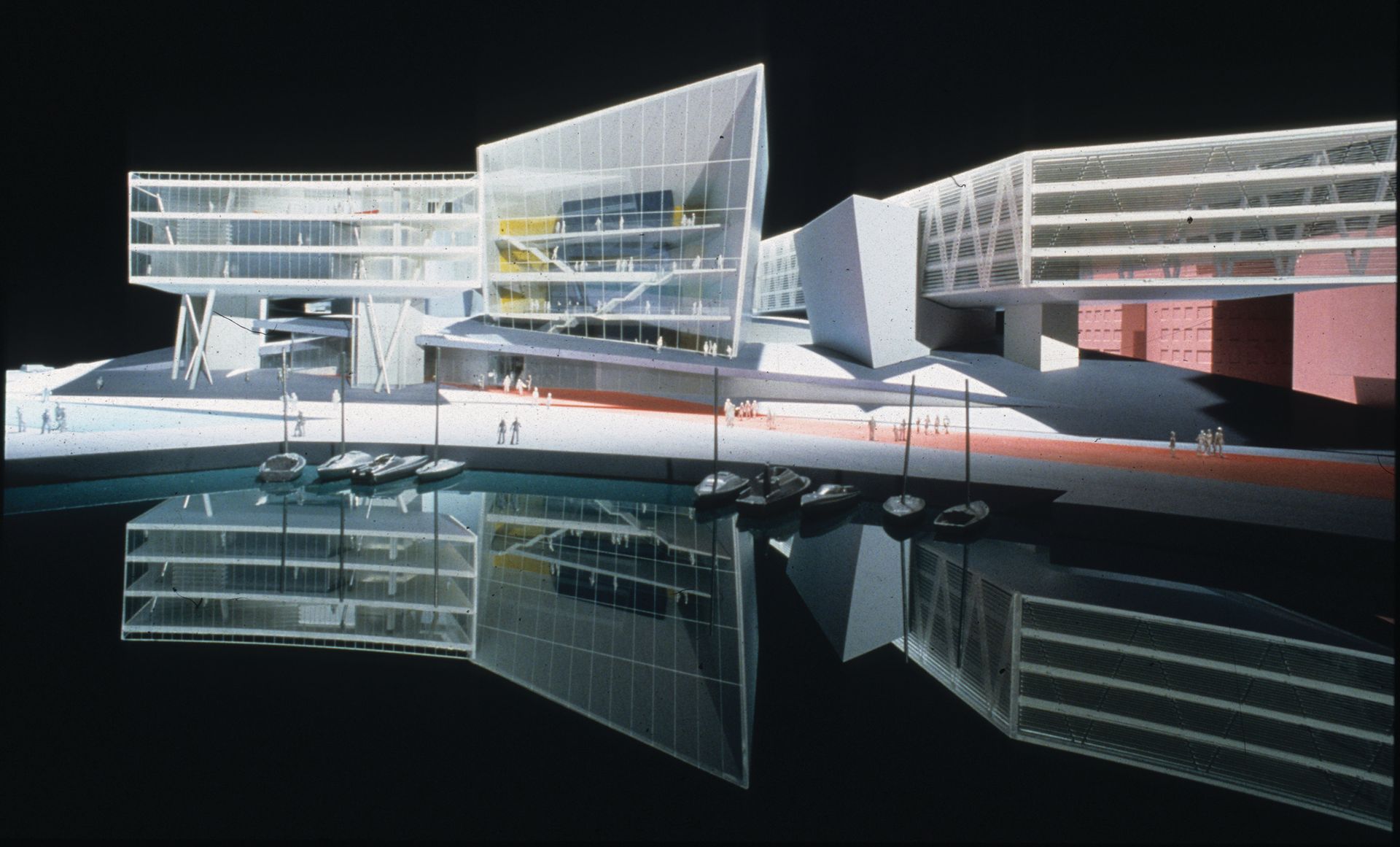

Vilnius Guggenheim Hermitage Museum (begun 2008)

Hadid won the competition with a “mystical object” hovering over an artificial terrain only for the plans to be postponed after the allocation of funds to other projects in Lithuania and a subsequent inquiry into financial murkiness. It may yet rise again.

MaXXI: Museum of XXI Century Arts, Rome (1998-2009)

The art and architecture museum’s wandering circulation and wayward walls that attempt to unite interior and exterior spaces are seen as either a welcome challenge or an obtuse nightmare by curators, but the project brought a welcome dose of the contemporary to the Eternal City.

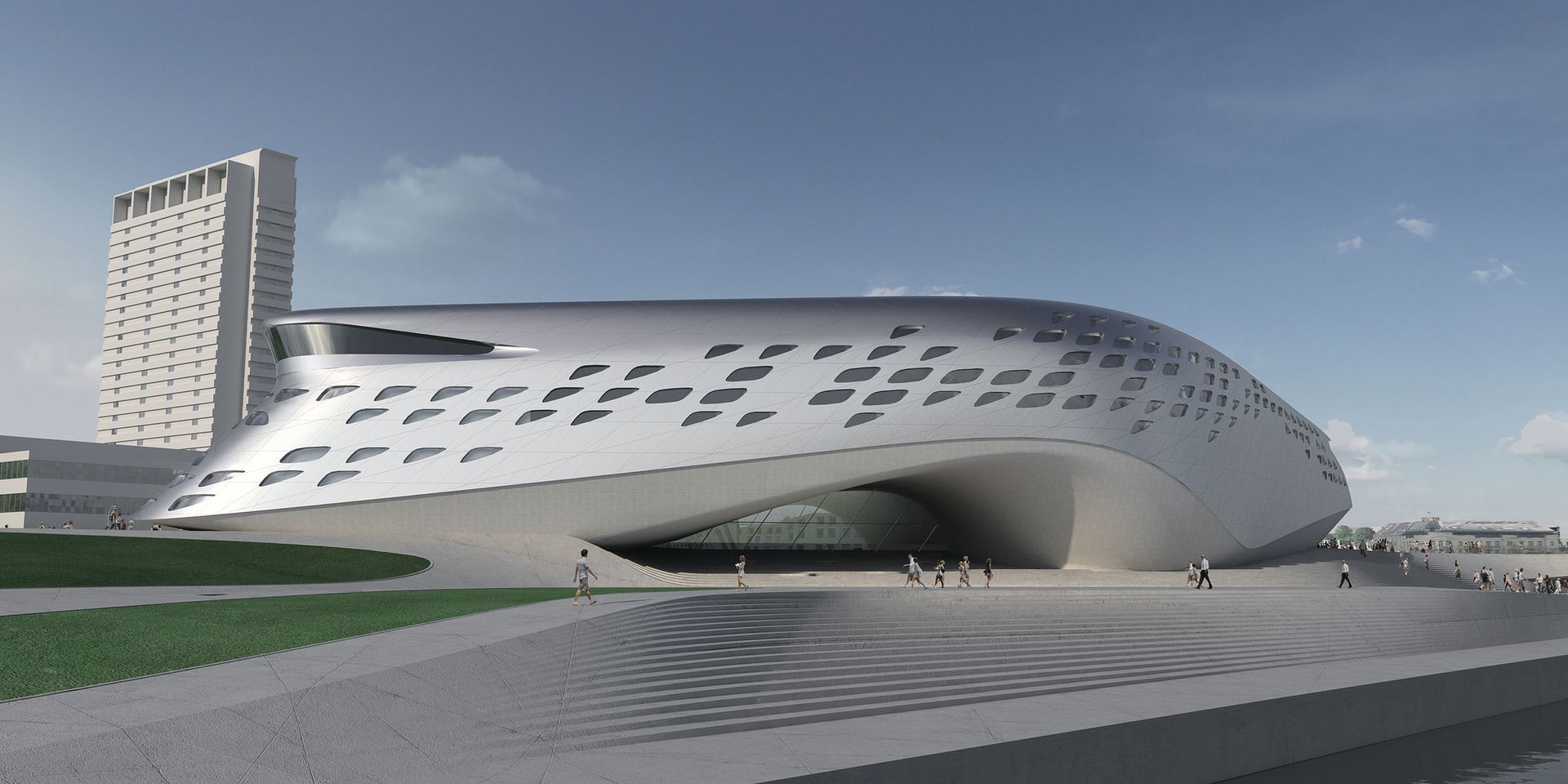

Heydar Aliyev Centre, Baku (2007-12)

Hadid’s astonishing artificial mountain range as cultural centre cemented her aesthetic prowess but left her ethics open to question here and in subsequent projects. The centre is named after Azerbaijan’s late dictator and Zaha Hadid Architects came under fire because of the oil-rich country’s treatment of migrant labour.