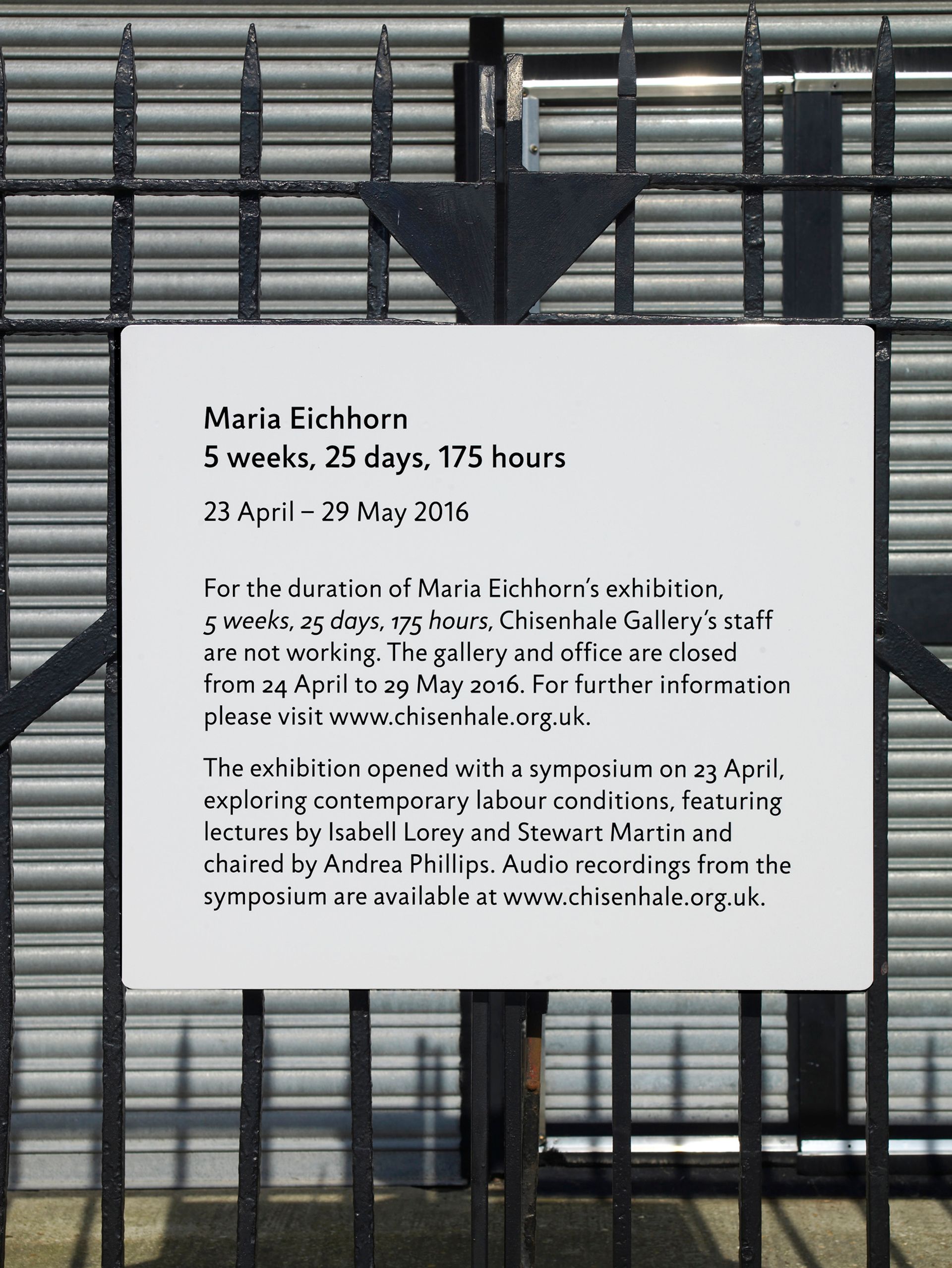

For the next five weeks anyone turning up to the Chisenhale Gallery will be met by closed shutters, locked gates and a notice stating: “For the duration of Maria Eichhorn’s exhibition, 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, Chisenhale Gallery’s staff are not working. The gallery and office are closed from 24 April to 29 May 2016.”

Try emailing the gallery or anyone working there and you will receive the following response: “I cannot read your email. Your email is being deleted. Please re-send your email after 29 May 2016 when I am back in the office.”

But this is not some mass Chisenhale Gallery protest at Eichhorn’s show—it is the show itself. As the gallery closes, so the exhibition opens with the request by the Berlin-based artist that all employees entirely withdraw their labour for the duration of the show. As Eichhorn firmly stated at a small patrons gathering, held last week before the shutters came down, what the Chisenhalers do during their five week (full pay) layoff was entirely up to them. “My work for Chisenhale Gallery consists in giving time to the staff, the only specification is that there is no specification. Once the staff accept the time, once work is suspended, the artistic work can emerge.”

The actual piece, therefore, is as much what the staffers decide to do, or not do—which they are under no obligation to divulge either during the exhibition or after the project ends. As Eichhorn was keen to emphasise: “The employees are not assigned any tasks by me. They should do nothing other than not work for Chisenhale Gallery.”

All of which opened up a lively debate around what constituted work and leisure time: were, for example, trips to private views or exhibition visits permissible, or did they constitute work? Then there was more unpicking of the practical implementation and ramifications of such a project: would a total cessation of activity have an adverse effect on a small and audience-reliant organisation like the Chisenhale? Would audiences and stakeholders be alienated? Would it not just cause a tsunami of outstanding work once they all returned after five weeks?

During what was the most animated discussion your correspondent has attended for a long time, it became immediately evident that this radical and provocative project—which is Eichhorn’s first solo show in the UK—was, before it had even started, fully living up to its avowed aim of operating not only in the form of the empty shuttered gallery but in the conversations and ideas that it was generating way beyond. Even the title is more complicated than it might at first seem: the exhibition’s 25 days refer to a five-day working week, but the 175 hours is based on a European 35 hour working week rather than a British one of 40 hours, with Eichhorn observing that “working conditions in London are rougher than in Berlin.” (Hopefully Chisenhale won’t be clawing back the outstanding twenty five working hours…)

Such multi-layered logistical and conceptual complexity therefore belies the initial straightforwardness of this work and make 5 weeks, 25 days 175 hours (until 29 May) possibly one of the Chisenhale’s most challenging shows to date, described by the director Polly Staple as “both a gift and a burden.” It is also a piece that, according to its creator, could be “rendered in any institution”. And indeed bought by anyone—though Eichhorn still needs to iron out the logistics on its afterlife. Maybe the new Tate Modern could pick up the gauntlet and, by closing, enact its most radical opening to date?