In 2009, two years before news of the Knoedler Gallery’s $70m sale of fake Abstract Expressionist paintings began to emerge, Ann Freedman resigned as director. Two years later, the venerable gallery closed down and the lawsuits against Knoedler and Freedman began to flood in. Five settled. The first to reach trial, brought by the collectors Domenico and Eleanore De Sole, also settled its claims against Freedman on 7 February (and against Knoedler shortly afterwards), just before she was set to take the stand in the New York courtroom. Her testimony had been eagerly anticipated, not least because she has never given her view of the unfolding scandal and her involvement in it. Until now.

Speaking to The Art Newspaper in an exclusive interview, her first in several years, she summed up the situation thus: “There has been a lot of misunderstanding.” We spoke to her in her sun-filled gallery on the Upper East side, FreedmanArt, which she opened in 2011. “Looking back, there can be things I didn’t see at the time…Could I have done some things differently? Not a day goes by that I don’t think about it. I don’t have an answer sitting here. I will at some point probably.”

Before granting us this interview, she made it clear that she would not respond point-by-point to the allegations made in multiple lawsuits—four are still active (see below)—and she would not engage in a “he said, she said” discussion. But she did describe how she understood the events, providing additional information in a phone call the following day.

How the events unfolded In 1994 Freedman was introduced to the Long Island dealer Glafira Rosales by a Knoedler employee who had met her socially. Soon after, Rosales brought Knoedler the first of 40 undocumented, previously unknown works, which Rosales claimed were original works by Abstract Expressionist artists. Nineteen years later, in 2013, Rosales confessed the paintings were fake and pleaded guilty to money laundering and tax evasion. She awaits sentencing, while the Justice Department is trying to extradite two of her co-conspirators from Spain. The Chinese artist who forged the works has fled to China.

Rosales told Freedman her anonymous client had inherited the paintings from his father, “Mr X”, who had bought them directly from the artists, but she provided few details. From the start, Freedman saw the story as a puzzle to be solved. She pressed Rosales for more information. “When you ask [con artists] a question, they say, ‘ah-hah, I see what you mean, let me check it out’. And miraculously they have the answers,” she said.

At one point, for example, Alfonso Ossorio, a Jackson Pollock patron, was identified as the person who helped Rosales’s anonymous client’s father buy art. But in 2003, the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) evaluated a Pollock from Rosales. It could not determine whether the painting was authentic or not, but concluded that the connection to Ossorio was “inconceivable”. Art-world figure David Herbert was then named by Rosales as the adviser to her client’s father, said Freedman. “I didn’t feed her names. I don’t know if others at Knoedler did” but “I asked her questions that made her figure out [a credible name to include in the provenance],” Freedman said. “I was a perfect mark, so I’m told, and my research helped them figure out their own scheme,” she said, describing those who conned her as “exquisitely conspiratorial wizards”.

How much did Freedman know? The multiple lawsuits’ central issue is whether Freedman knew—or should have known—that the works she sold were fake. “I have never deliberately done something wrong, which is to say knowingly,” Freedman said. “It doesn’t mean I haven’t…done things that I would like to take back…Mistakes happen. Since the beginning of mankind we have seen mistakes with thinking something is, and it isn’t. There’s no greater ripe field for it than works of art. [Even] museums know they have questionable works.”

Freedman described herself as a dealer and lover of art, but said she was not an expert or connoisseur. “I always looked to scholars.” Former National Gallery of Art curator E.A. Carmean, who did research for Knoedler, and the Mark Rothko scholar David Anfam were among those who believed in the works. Robert Motherwell’s wife, the artist Helen Frankenthaler, saw one of the fakes and said, “‘Yep, it’s Bob.’ You can’t get better affirmation than that,” Freedman said.

The plaintiffs in all the lawsuits contend that Freedman ignored clear warnings. For example, they say, Rosales offered Knoedler many works at below-market prices. At the De Sole trial an expert in dealer practice, Martha Parrish, testified that when that happens a reputable dealer would “run like hell”.

Freedman said she didn’t think anything was suspicious. Rosales had described the owner of the forged paintings as coming from a wealthy family and she said he wanted to get rid of the paintings but not give them away. Art often enters the market through divorces and inheritance, which can be messy, said Freedman. Some people want top dollar. Others just want to be rid of their art. “When you separate yourself from something, that takes on a different value than if you want it,” said Freedman, adding that in the course of her career it has not been only Rosales who said to her, “I don’t want [this work of art]…give me something for it.”

Inconclusive report The plaintiffs also point to IFAR’s report, which rejected the provenance for the forged Pollock painting supplied by Rosales. The report concluded it could neither prove nor disprove the painting was authentic and cited some negative comments from experts. Freedman’s belief in the painting did not waver; there was a recent history of bad feeling between IFAR and Knoedler, and the experts consulted by the organisation were anonymous, she said. “If there’s a reason for doubt,” how could this be evaluated without knowing who is raising the doubts, Freedman asked.

In 2008, in response to suspicions by the Dedalus Foundation, which maintains the Motherwell catalogue raisonné, Knoedler hired forensic conservator Jamie Martin to test Motherwells supplied to the gallery by Rosales. His analysis cast doubt on the paintings’ authenticity. “He knew nothing about Robert Motherwell,” Freedman said, pointing out that Carmean, who did know Motherwell’s work, “took Martin’s report apart”. Of course, Martin “turned out to be right”, said Freedman, but she didn’t think so at the time.

What the plaintiffs call red flags only “gave me more fire to be proving better and harder what I believed”, Freedman said. “I always thought that tomorrow I’ll find a photograph of the artist’s studio and see the corner of [one of the forged paintings.] When you’re doing research, you’re like Christopher Columbus. You’re not sure when you’re going to find land.” In Freedman’s case, she never did.

And now? “I am terribly sorry for anybody who [says they have been] hurt or damaged…But let me be clear, this is [about] works of art. I didn’t slay anybody’s first-born. We have to have some perspective on suffering.” Freedman recounted what an unnamed art historian told her: ‘We all need to get over it.’ I’ve had a debacle to deal with…I’m not hiding it,” Freedman said. “But you go on…You have to have a good conscience to keep going.”

Six lawsuits down, four to go After the Knoedler Gallery closed in 2011, ten lawsuits were filed in Manhattan federal court by collectors who bought fake Abstract Expressionist paintings from the gallery. The lawsuits allege that Knoedler and its former director Ann Freedman knew or should have known that they were selling fakes. The forged paintings, 40 in all, were brought to Knoedler by Long Island art dealer Glafira Rosales from 1994 to 2008. The collectors allege that each purchase was part of a conspiracy, and are seeking triple damages under a federal conspiracy statute, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. Knoedler and Freedman deny any wrongdoing.

Six lawsuits have been settled. The following are still active and in pre-trial proceedings:

• Frances Hamilton White, a California collector, and her then-husband bought a “Jackson Pollock” in 2000 for $3.1m. Knoedler paid Rosales $670,000. According to the complaint, in February 2011 Christie’s declined to accept the painting for auction because it was not in the catalogue raisonné, and Knoedler refused to take the work back.

• The Martin Hilti Family Trust, in Liechtenstein, bought a “Mark Rothko” in 2002 for $5.5m. Knoedler paid Rosales $750,000.

• Frank J. Fertitta III, a Las Vegas casino owner, bought a “Rothko” in 2008 for $7.2m. Knoedler paid Rosales $4.5m. According to the complaint, Knoedler paid Oliver Wick, a former Beyeler Foundation curator, a $300,000 consulting fee.

Correction: Rosales was paid $4.5m for the "Rothko" sold to Fertitta, not $700,000 as was mistakenly reported.

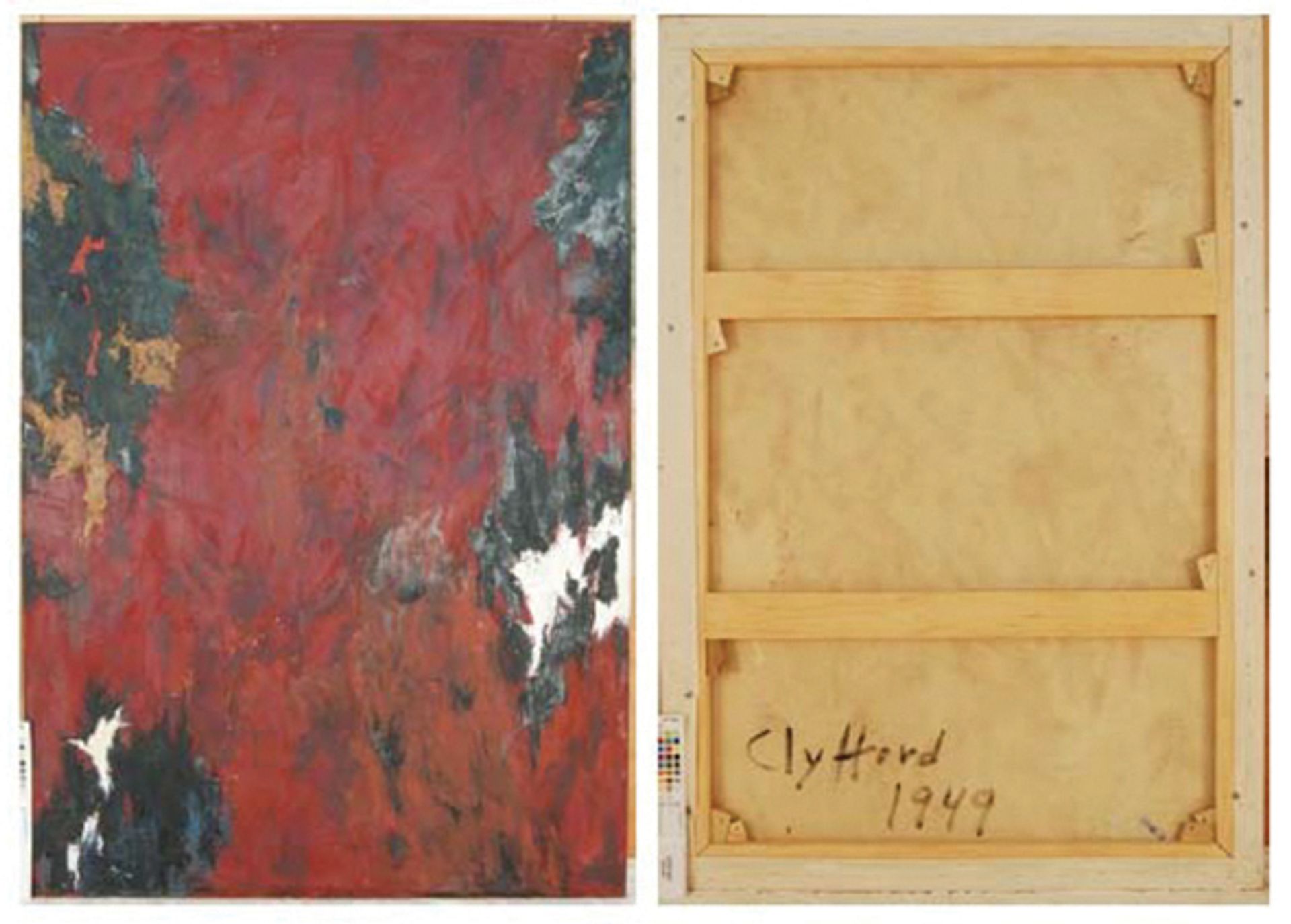

Update: Freedman settled a lawsuit brought by the Arthur Taubman Trust, Nicholas and Eugenia Taubman. The trust bought a “Clyfford Still” in 2005 for $4.3m. Nicholas Taubman is the former US ambassador to Romania. Knoedler paid Rosales $600,000. In 2007, Taubman negotiated with Knoedler to purchase a “Pollock” that had been evaluated by the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) that could not support the painting's addition to the artists' oeuvre. Freedman never showed IFAR's report to the Taubmans. The deal fell through when Knoedler refused to sign a contract saying that it didn’t know of any facts that called the authenticity of the painting into question.

For a letter in response to this article from Sharon Flescher, the executive director of IFAR, click here.