God is the Light of the Heavens and the Earth: Light in Islamic Art and Culture is a glossy, profusely illustrated volume resulting from a Palermo symposium with contributions by well-known scholars. The Gulf: High Culture/Hard Labor is a cheaply produced paperback by lesser-known artists and social commentators. What connects two such disparate publications?

Light is an enduring topic in Islamic science and art history, much of the discussion stemming from a well-known topos in the Sura of Light (Koran 24:35), where the image of a lamp in a niche is related to revelation of the divine. But God is the Light of the Heavens and the Earth opens with a contribution by Shirin Neshat, a celebrated Iranian photographer for whom light is a medium rather than a subject of discussion. Rebellious, especially regarding the status of women, and inflammatory in the Middle East, much of her work has been made in the West, but she acknowledges her retention of certain traditional characteristics found in Islamic art: patterns of repetition and symmetry, and a preoccupation with text. She asks the interesting question: “Is Western culture reductive?” by its lack of national and historical differentiation within the Muslim world, although she appreciates the freedom to be found in the West.

Nishat’s contribution is a fascinating account of her work, but does not take up the overall theme, which is more closely followed in another essay, William Graham’s discussion of early exegeses of the Sura of Light, especially the interpretation of this complex simile by al-Tabari, the ninth-century scholar. Graham notes that early commentators interpreted it to mean that Muhammad was the possessor of light and that, for the Shi’a, Muhammad’s daughter Fatima is the niche within which the light rests and her sons are represented by the lamp.

Graham is concerned with literary sources, but a frequent motif in artistic representation is the “shekhina”, the divine light of prophecy which descended on Muhammad, shown as a golden aureole or flames. This is discussed by Barbara Brend in her analysis of light in Persian painting, which surveys both the material incorporation of gold and silver, and the production of illumination effects. With the aid of modern technology, Brend has been able to restore luminosity to the now-tarnished and blackened sea of silver where Iskander’s mermaids sport in an early 15th-century anthology. This subtle study explains the achievement of light effects in those magical-seeming scenes where an arena is created through darkened implications of skies and landscapes.

Brend understands how Persian painters elegantly resolved the perpetual problem of the artist, East or West: how to get light into a picture. Brend also discusses the gradation of colour to obtain the effects of volume and modelling, but does not go on to explore the absence of shadow in Islamic art, nor consider the question of why the painters, so skilled in the manipulation of lighting effects, did not introduce shadow and its possibilities.

A study of the lavish Korans of the Mamluk era, where heavy gold leaf explodes in geometric stars, would have rounded out the contributions on manuscripts, but those superb gilded copies are not considered here, though they would have also extended the focus geographically from Iran to Egypt. However, Susan Stronge takes the reader to India in a fascinating study of the “imperial halo”, the golden rays surrounding the heads of Mughal rulers, interestingly extended from observations into gold coinage.

Hakan Karateke’s cheering history of ceremonial Ottoman fireworks is illustrated with manuscript paintings of displays; a particularly dazzling show involved rafts floated on the Golden Horn setting off burning wheels, rockets and fiery cascades. The skills of the artificers originated in the serious business of the armourers of the imperial troops and these ephemeral arts required considerable scientific development.

Illumination had been explored in scientific thought by Ibn al-Haytham, better known in the West as Alhazen, whose late 10th- or early 11th-century studies preserved the work of Ptolemy and had a long influence on the study of optics. Elaheh Kheirandish summarises the “spectral history” of al-Haytham’s theories, though I am puzzled that she follows A.I. Sabra in claiming that al-Haytham’s Optics were “unknown or unused in his native lands”. Brockelmann’s Geshichte der Arabischen Literatur cites five known Arabic manuscripts ranging over three centuries to as late as 1509, and the work also survived through al-Farisi’s well-known commentary.

Light, natural or artificial, in the context of architecture is tackled in an essay by the doyen of the subject, Robert Hillenbrand, whose well-ordered thought and clarity might be a model for younger art historians who want to spread knowledge rather than clothe a complex topic in still more difficult obfuscation. From the grand to the small but perfectly formed, we move from Hillenbrand’s architecture to Anna Contadini’s contribution on rock crystal, especially valuable for the technical understanding that Contadini brings to the extraordinary processes involved in working with this most frangible but beautiful of materials.

Allied to questions of transmission and refraction are Oliver Watson’s experiments on translucency in ceramics. He explains the Egyptian potters’ development of a white fritware, which by the 12th century could rival the thinness of Chinese porcelain. This was perfected in astonishingly delicate filigree work. We need no longer assume that the famous traveller’s description of pottery in Cairo so delicate that one could see a hand through it referred to Chinese imports. Watson’s photographs of the transparency of Islamic fritware are a revelation.

The overall academic standard is remarkably high and the book is edited by two leading lights in the Islamic art field, Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom. This collection brings fresh and informative material by respected scholars. Why, then, does it generate a sense of unease?

The answer lies in the sponsorship, which raises profound questions about the basis of Islamic art studies in general. This book, like the symposium that gave rise to it, is supported by the Qatar Foundation of the Virginia Commonwealth University, which now has a campus in Doha. Qatar, as is made clear in The Gulf: High Culture/Hard Labor, has a very questionable record of labour rights, and recent reforms are so minor as scarcely to touch the abuses of the kafala system of servitude, whereby a worker pays to be recruited, must repay this sum and cannot leave without permission.

The abuses prevalent in Qatar were documented in an article by Richard Morin in The New York Times of 12 April 2013. Clearly, little has changed. Art has always been the toy of rich patrons, but the unique feature of Gulf collections is that, where they are on public display, they are generally inaccessible to all but the well heeled. The kafala workers inhabit a different world.

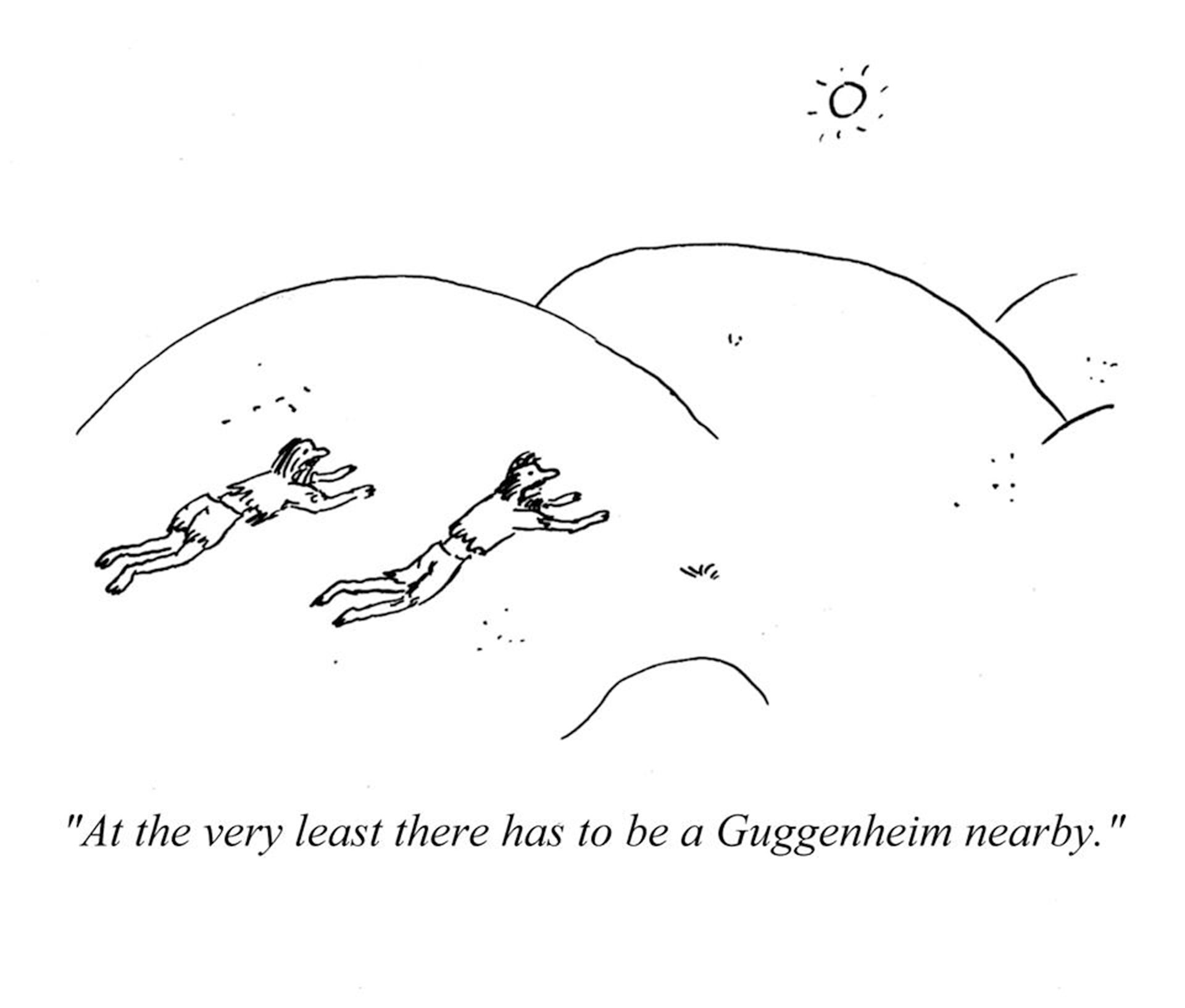

It is with some relief that one can turn to the contributions of practising artists to The Gulf: High Culture/Hard Labor, where the general theme is art as resistance. However naïve they may seem, these are documentations of painful contemporary life. And no one could fail to laugh at Pablo Helguera’s cartoon where two exhausted travellers are crawling through the desert and one says to the other: “At the very least there ought to be a Guggenheim nearby.”

The involvement of Gulf states in cultural enterprises and their welcome in the West following vast endowments are moral problems for participating individuals and institutions. There is a good reason why Islamic art historians accept opportunities to put their subject before a Western public: the desire to present a positive view of Islam at a time when prejudice and misconceptions need to be dispelled.

But Qataris have now funded so many institutions that it is time to ask not only the moral questions, but the pragmatic one of how this is distorting the field of study? God is the Light of the Heavens and the Earth, for all its virtues, is a pet of the rich: like their collections, its contents are beautiful, hermetically sealed in the past and inevitably present Sunni Islam in a very good light indeed.

• Jane Jakeman has a doctorate in Islamic art and architectural history from St John’s College, Oxford. She has been on the staff of the Bodleian and Ashmolean Libraries and was librarian to the Oxford English Dictionary. She is also an author and reviewer of crime fiction

God is the Light of the Heavens and the Earth: Light in Islamic Art and Culture

Jonathan Bloom and Sheila Blair, eds

Yale University Press in association with Qatar Foundation, Virginia Commonwealth University and Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts in Qatar, 376pp, £50 (hb)

The Gulf: High Culture/Hard Labor

Andrew Ross, ed

OR Books, 360pp, £13, $20 (pb)