It’s no secret that Glasgow has a great art scene, but this year’s Glasgow International—a heady, sprawling mix of 78 exhibitions by 220 local and international artists, established and unknown—has a particular energy. The festival is dominated by women but doesn't proclaim this and much of the work is about the city itself: the legacy of its past industries, its current colonisation by artists and what it now means to labour and to produce. Distinctions between the festival’s official programme and fringe events often blur—but in a good way—and there’s also a terrific performance programme of more than 50 events, which frequently accompany and further augment the exhibitions. The biennial is only on until the end of the month and here are a few not to miss.

Glasgow International 2016: Director's Programme, Tramway (until 22 May)

The festival’s post-industrial themes are given a good airing in this group show curated by Glasgow International’s director Sarah McCrory. A fibrous, ceiling-high column of vivid yarn from octogenarian Sheila Hicks ends in soft netted cloth boulders and sends seeping, clogging trails of bright wool into the redundant tracks of this former tram factory and depot. The Cologne-based Alexandra Bircken’s wheeled metal-trolley sculptures have also come to a halt here—strung with textile meshes like a makeshift encampment. Another defunct symbol of the city’s past heyday, the Clyde-built QE2 cruise liner, features in Lawrence Lek’s computer-generated film and accompanying model. The ship has been taken out of its current Dubai dry dock, split in two and upended to form a novel new home for Glasgow School of Art, whose Rennie Mackintosh designed building was gutted by fire two years ago.

Pearls are force-cultivated, lettuces pounded and plates of pasta sneezed into existence in Mika Rottenberg’s relentless and excruciatingly visceral satire of endless, pointless labour. While Amie Siegel’s Provenance (which closes on 25 April) takes a long cool look at our current economies of art. Siegel’s sumptuous film traces the route of sought-after modernist furniture from the Le Corbusier-designed north Indian city of Chandigarh, back through the restorers, auction houses, dealers and collectors to its functional, utilitarian origins in everyday offices and courthouses. A second film completes the circle by recording that Provenance itself then went under the hammer in 2013, thus becoming another commodity in the market it depicts.

Cosima von Bonin: Who’s Exploiting Who in the Deep Sea? (until 7 August) / Tessa Lynch: Painter’s Table (until 12 June), Glasgow Museum of Art

Scaled-up soft marine creatures by Cosima von Bonin bring some seaside surrealism to the main hall of Glasgow Museum of Art as they loll and loom on loungers, low plinths and—in the case of one ominous fat stuffed bird—straddle a giant rocket missile. They are more boisterously cartoonish than unsettling, although there’s a malevolence to the tweed octopus whose tentacles end in savagely pointed glass curlicues, and the pair of clams balancing on twin skateboards, with eyeballs peeping from their half-open shells.

Recent Glasgow School of Art graduate Tessa Lynch presents a subtler and quietly incisive parallel universe based on her personal perambulations across the city. Wryly casting herself as a female flâneur—a flâneuse—she observes and remakes Glasgow’s urban structures, situations and surfaces in unexpected and arresting ways. Whether the hand-woven tapestry bricks, tiny laser-cut aluminium sculptures, voluptuous plaster panels or a Perspex canopy that gently dribbles rain water, all combine to riff on Minimalism, machismo and much more.

Claire Barclay: Bright Bodies / Helen Johnson: Barron Field, Kelvin Hall (until 25 April)

The derelict, decaying Kelvin Hall used to house circuses as well as trade and industrial exhibitions. In the peeling former grandeur of an upstairs function room, Clare Barclay’s extensive, suggestive installation uses lengths and cascades of pink rubber; caged red-canvas sacks spitting coal dust; drilled machine parts and sheets of metal puddled with coal tar to filter the building’s past ghosts through the formal language of 20th century abstract sculpture.

Downstairs a hanging maze of large, unstretched, suspended canvases by Australian artist Helen Johnson take scenes from classical mythology as a starting point to unpick on-going legacies of colonialism. And in doing so point to the similarities between today’s art festivals and Kelvin Hall’s past events, which also showcased endeavours and achievements from all corners of the world. The artist’s thought-processes are revealed by extensive notes and references written on the canvases’ exposed backs and it is also a treat to get up close and revel in her luxuriant range of techniques: from Artex-like low relief patterning to delicate, intricate drawing and almost trompe l’oeil detail.

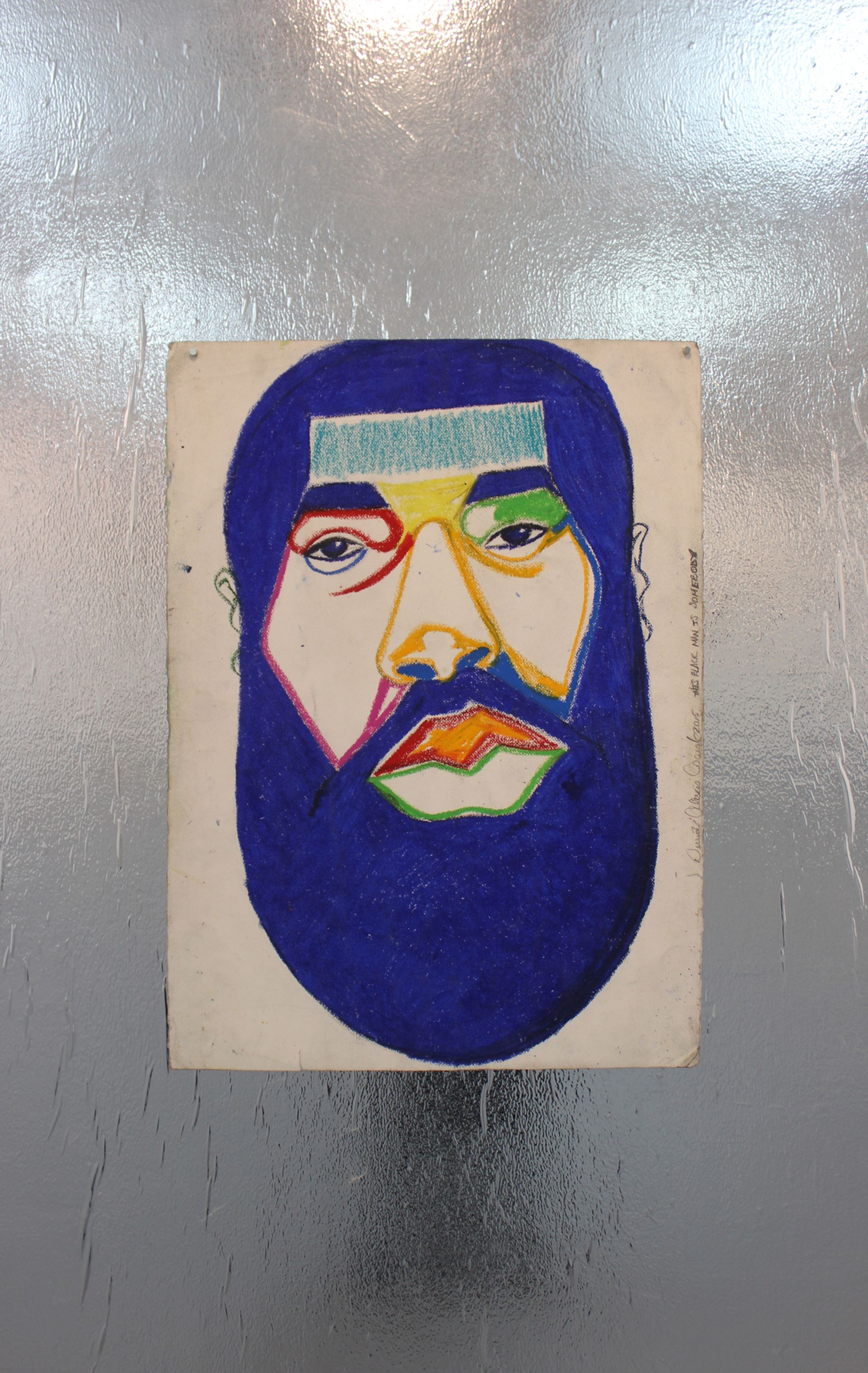

Derrick Alexis Coard and Mark Leckey, Project Ability (until 21 May)

A show of intense, imaginary portraits of bearded African-American men drawn and painted by this self-taught artist, who is affiliated with New York’s Healing Arts Initiative, a centre supporting adult artists with mental illnesses and developmental disabilities. Often these stern, inscrutable heroes are imbued with affirmative titles such as Wisdom Advisor and Humble Thug as their maker sees their role being to reverse negative stereotypes. As well as being curated by Matthew Higgs of New York’s White Columns, this show also has the additional dimension of respectful interventions by Glasgow’s Mark Leckey. These include a mirrored wall and an elegant, suspended squiggle of inner tubes, which Leckey describes as his rubberised riposte to the plethora of beards lining the walls.

Louis Michel Eilshemius, 42 Carlton Place (until 15 May)

A revelatory show of an eccentric maverick that was championed by Marcel Duchamp and became a cult figure in US and European avant-garde circles of the 1920s and 1930s before being largely forgotten until now. Although academically trained, Eilshemius developed an idiosyncratic and seemingly—but absolutely not—naïve style that could be visionary, abstract, sometimes surreal and often wilfully amateur. Many of these bizarre paintings foreshadowed the deliberate deskilling and deliberate “bad painting” of Francis Picabia et al, but they also have an oddly compelling quality all of their own.