Has there been a more violent white picket fence in the history of American photography? White Fence, Port Kent, New York (1916) is one of the first images you encounter in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exemplary show on the US photographer Paul Strand (1890-1976). The depth of field has been flattened turning the two buildings in the background into rectangles, while that white picket fence cuts across the picture frame like a set of train tracks laying claim to the Wild West.

It is an apt opening salvo, showing both Strand’s interest in notions of the American dream and his exquisite ability to fill frames to the edge and to evoke, or play off, what is omitted as well as what is present.

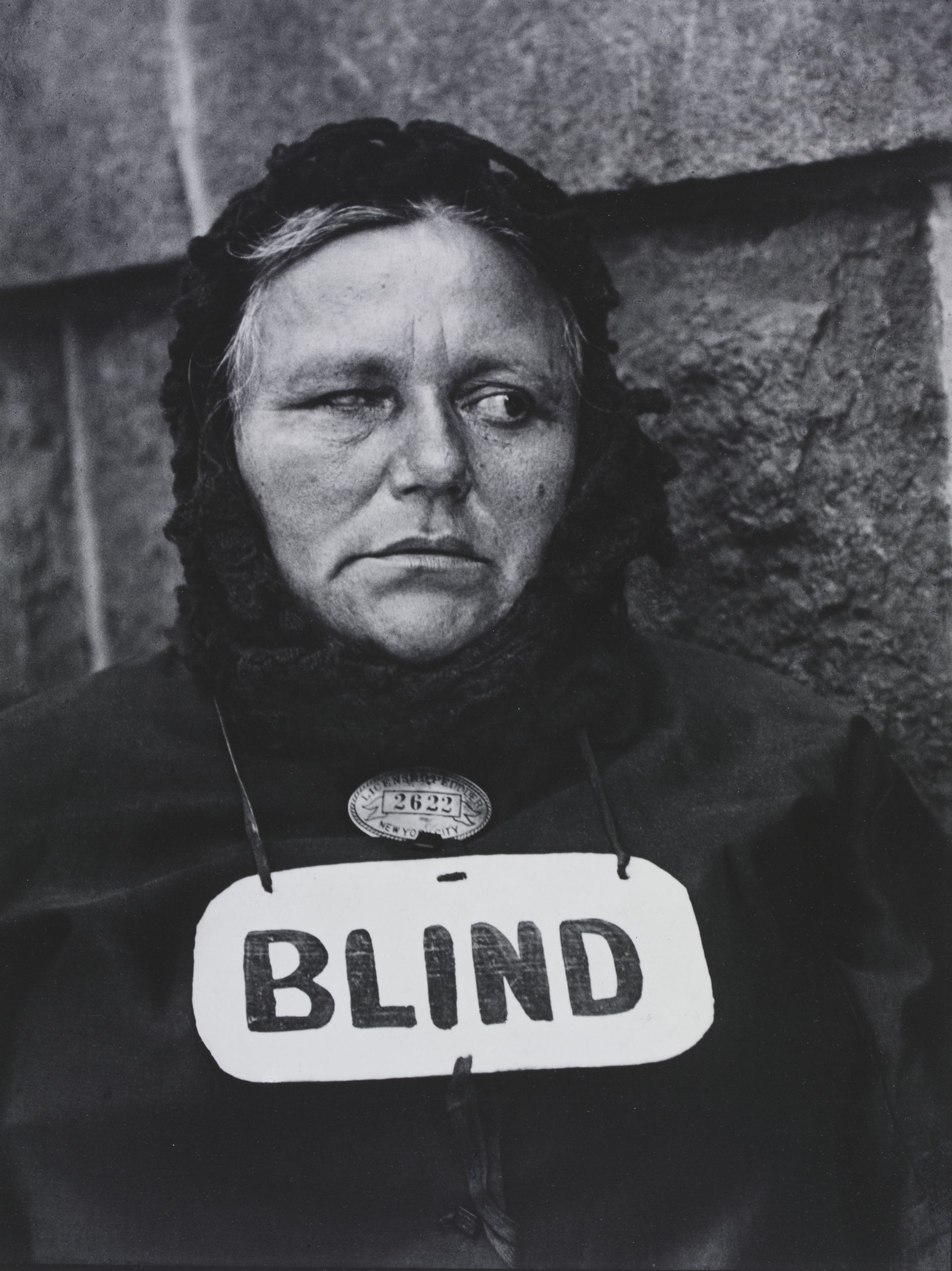

Similarly, the framing of Wall Street, New York (1915)—the monumental calling card for this exhibition—shows silhouetted figures on the way to work in front of the vast and imposing JP Morgan office, framed so that it becomes a building of seemingly endless and impossible dimensions. Strand is probably best known for the work he made in his native New York and his street portraits made using a decoy camera lens—to catch the subjects unawares—are certainly some of the most powerful in the exhibition. These rich and sombre images seem to exist in that moment of twilight where your eyes take an extra second to detect detail or movement that is nonetheless definitely there—such as the upturned eyes of The Italian (1916) shaded by his low-brow that abruptly come to life as he casually leans back on a stone wall. The feeling is reminiscent of the scene in Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), when the eyes of the protagonist suddenly move after a whole film of photographic stills.

Strand’s first film Manhatta (1920-21), made in collaboration with the painter and commercial photographer Charles Sheeler, appears similarly photographic rather than filmic, like a slide show that has come to life. The static, at times almost abstract, shots framing the city are interspaced with quotes from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855), and the final scenes of the Manhattan skyline is a sumptuous precursor to Empire (1964), the static eight-hour film of the Empire State building by Andy Warhol.

Leaving behind this relatively small part of the show on Strand’s New York, the rest of the exhibition documents his extensive travels from the 1930s onwards, taking in parts of the US, Mexico, France, Egypt, Morocco, Ghana and the Outer Hebrides. The visit to the latter, and subsequent photobook, came about after Strand heard a Gaelic folk song broadcast on the BBC. As you stand in front of Mrs. Archie MacDonald (1954), one of two welcome surprises in the exhibition occurs as you trigger a motion-activated recording of MacDonald singing a capella, a beautiful and mournful melody.

This is the second such surprise, the first is the voice of Helen Bennett—whose portrait was taken for War Bride, East Jamaica, Vermont (1943)—as she recounts a visit by Strand. After directing her to stand in front of the window and setting up his equipment, he “didn’t say much of anything else”. Strands ability to empathise with his subjects and let them breathe, so to speak, in front of the lens is what is so disarming and alluring. “It couldn’t look any more like my father than it does”, Bennet says of the accompanying image—Mr. Bennett, East Jamaice, Vermont (1943)—seemingly stating the obvious but neatly summing up the photographer’s ability to capture the “true” likeness of his sitters.

Strand lived out the final years of his life in Orgeval, France, and the show ends with close-ups of forest undergrowth, harking back to earlier works he made in the 1920s with 8 x 10 inch film, and printed up in the same size. The detail in some of these photographs, such as Toadstool and Grasses, Georgetown, Maine (1928), is enough to make you gasp and is a reminder of his love for the tools of his trade—examples of some of the bulky cameras are on display too—and his adeptness at cropping and alluding to more by showing you less.

• Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century (until 3 July)

Victoria and Albert Museum, London