Primary Structures was a watershed. When the show opened at the Jewish Museum in New York on 27 April 1966, it helped usher in a generation of artists who raised fundamental questions about the nature and purposes of three-dimensional art. The “younger American and British sculptors” referred to in the show’s subtitle were “impelled to test primary definitions and basic aesthetic issues”, as the curator, Kynaston McShine, wrote in his catalogue essay. They were impelled, in other words, to get to the core of their crafts.

The art was not immediately popular. The work on view, by 42 artists including Donald Judd, Anthony Caro and Judy Chicago, was cold and hard—the opposite of the Abstract Expressionist painting New York audiences had only recently grown accustomed to. Critics such as Hilton Kramer, in the New York Times, underestimated the art, deeming it a simple intellectual exercise. “One is enlightened, but rarely moved,” he wrote.

Exactly 50 years on, with many of the names from the show now part of the artistic canon, we look back at the exhibition by talking to those closest to it.

Primary Structures did not inaugurate Minimalism. By the time the show opened, several exhibitions and publications—including the show Black, White and Grey at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1964, and Barbara Rose’s landmark essay ABC Art from 1965—had already begun to pinpoint the key tendencies of recent painting and sculpture. “Primary Structures consolidated the conversation at a point where the discussion around the art had matured,” the art historian James Meyer says. As the artist Larry Bell, who was included in the show, puts it: “If Primary Structures hadn’t happened, there would have been another show. These guys were not going to be ignored.”

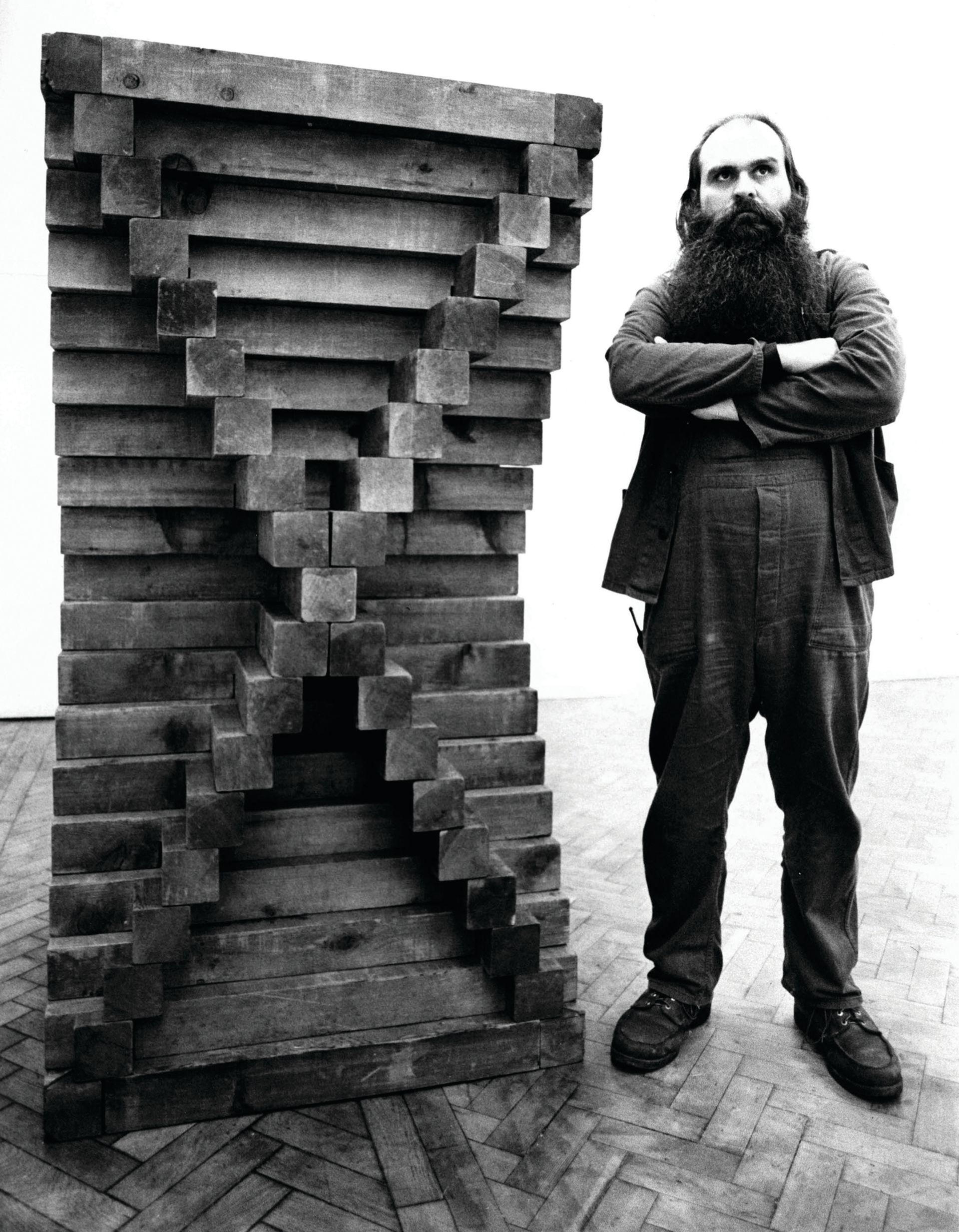

Carl Andre, artist: Momentum was already building around what’s called Minimalism. I started doing work that was primitively recognisable as Minimalism, starting in 1959. Minimalism was my tendency anyway because I was inspired by [Constantin] Brancusi, a

“minimalist” artist who reduced his form to the most basic elements. Minimalism wasn’t new; it was just a distilled essence of what happened before. Not that it was any better—it was just a new version. Every night we were at Max’s Kansas City, bullshitting about art. Robert Morris, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd—I knew all those artists very well. Between us, there was a constant conversation. So there was already a conversation developing around it.

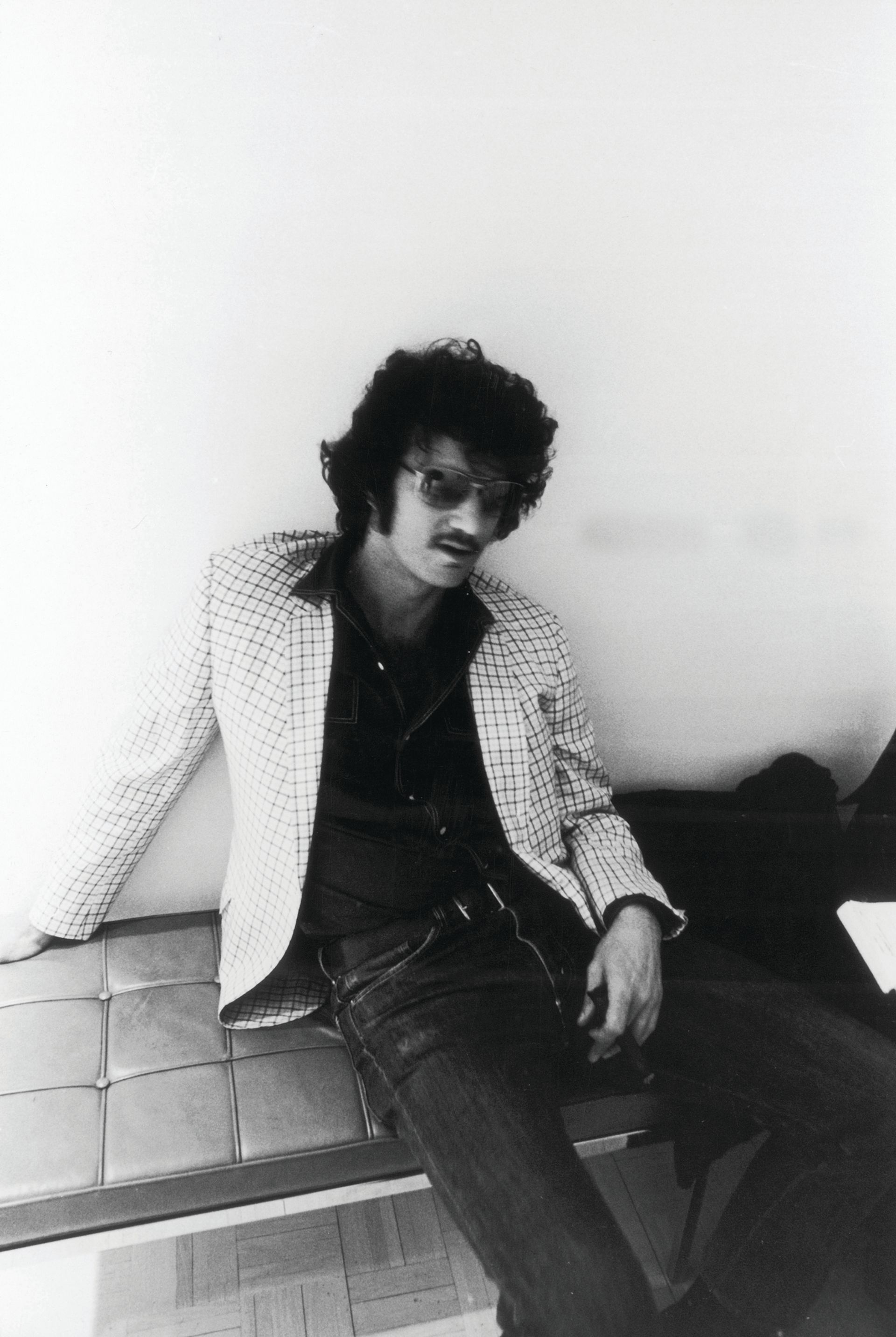

Mel Bochner, reviewed the exhibition for Arts magazine in June 1966: I thought it was logical. A lot of people were thinking about it. You want to break free of Abstract Expressionism, and where do you go from there? I knew Judd as a writer—I was a great admirer of his writings—so if there was any inevitability, it was that his sculpture was the inevitable outcome of his writing. But just put it this way: it looked fresh—it looked new. It was not something you’d seen before, and that was exciting.

Judy Chicago, artist: It was quite a surprise for Kynaston McShine to have organised it at the Jewish Museum. Why didn’t the Whitney do that show? Why didn’t the Museum of Modern Art do that show? Why weren’t they out in front? I think what I’ve learned over the years of my long career is that it’s usually institutions on the edge that tend to do edgy things. The mainstream institutions tend not to take a lot of risks.

“My friend Don Judd can’t qualify as an artist because he doesn’t do the work.” This accusation, levelled by the sculptor Mark di Suvero during a panel organised on the occasion of the show, was pervasive. The artists in Primary Structures were tasked not only with making their art good, but with making it relevant at all. “I got the question over and over again,” Andre says. “‘How can you call that art? That’s not art! You bought it from a supplier and put it on the floor.’ I replied that I didn’t want to ruin the material. I wanted to show matter as matter. Some artists are very good colourists but I’m a matterist—matterism is my concern.”

Larry Bell, artist: You can take [di Suvero’s] position, but it’s a little bit like somebody saying that you’re not doing real music because it’s not acoustic. An artist is responsible for everything. Everything good that happens to an artist’s career, an artist is responsible for, and everything that’s bad about an artist’s career, the artist is responsible for.

William Agee, critic, curator and professor of art history, Hunter College, New York: Judd and Flavin were testy, defensive—they had to be because their art was constantly attacked. Older artists thought it was neo-Dada, that painting as we knew it had ended. Yes, di Suvero’s attack was widespread. There was no obvious labour, and art was thought of as hard labour. They didn’t understand the process, at least for Judd. He made thousands of drawings [of] his ideas before he could settle on an exact piece. It’s a great example of [the philosophy of] American pragmatism raised to a working methodology.

Phillip King, artist: I remember a young, ambitious sculptor—whose name I’ve forgotten now—who was, I think, a stockbroker or something, and decided to make sculpture. But he didn’t want to dirty his hands, so he started being a sculptor from being a finance man by ordering sculpture on the telephone, and that was his pride, to be able to do that. And I think he had quite a successful show out of work done that way. It was obviously in the air in New York at that time, the idea of conceptualising your work so much that you didn’t have to physically be very involved with it. But that was something alien to me, certainly. I have always had a very hands-on approach.

The artists and curators were friends and foes… Artists need curators. Without the institutional weight of people such as McShine, whose catalogue essay heralded difficult new sculpture, much of the art would have gone unseen. But there was also friction. Some of the artists—Phillip King and Carl Andre included—were unhappy with how their work was presented. And not everyone benefited from the legitimacy that curators could confer.

Phillip King: I never went to the exhibition. I met Kynaston McShine, who I think came over [to the UK]. I can’t remember much about Kynaston, but he was a nice bloke and we got on well. And he organised the show and subsequently I got the catalogue, and I was a bit mad and fed up because they manipulated the

photograph of Through [1966, King’s work in the show], and they deliberately didn’t print the bottom half of it, so it looked much more Minimalist that it was intended to be. I wasn’t aware of it being Minimalist in any way. I wasn’t trying to be Minimalist, but they obviously wanted it to be more Minimalist, and so when they printed the photograph they deliberately left out the bottom part, with the steps.

Carl Andre: I was asked to come to the Jewish Museum and select a site for the installation of my work. I wanted to do a corner piece and this required that I have a blank wall—no doors, fire extinguishers or anything like that. The museum said “fine”, but when it came time for the show to be installed, [the architects Robert] Venturi and [John] Rauch were invited to do the installations. I thought this was an act of treason—they are interior designers, not artists. They installed my work next to the door, fire extinguisher and everything else that I didn’t want. I told them that this was an abjection of my work, so I pulled my work from the show. But the museum had another work of mine, a line piece [Lever, 1966], and they showed that instead. I felt cheated and lied to. They had gone back on their promise. There was a piece in the show, but it was not the corner piece that I intended.

Judy Chicago: One of the things that was different for the women artists of my generation was how my male peers would be in a big show and all these things would happen for them—but for me nothing happened. [The curator] Walter Hopps refused to look at [Chicago’s sculpture Rainbow Pickett from 1966, which was included in the exhibition]. Refused to look at it. I wrote about this in my first book, Through the Flower, and I hadn’t mentioned his name but he had apparently read it because he called me up to apologise. He said: “You have to understand that, at the time, women were either groupies or artists’ wives, so what was I supposed to make of the fact that you were making work that was stronger than the men’s?”

The market was small… In the 1960s, few young artists made much money from their work. The handful of New York dealers that showed Minimalist art, such as Arne Glimcher of the Pace Gallery and Richard Bellamy of the Green Gallery, often turned little profit. Bellamy’s gallery closed in 1965 after only five years when funding from the collector Robert Scull dried up. But there was less money everywhere. Chicago remembers renting a 5,000 sq. ft studio with two others for a mere $75 a month (around $563 today). “It was possible to live on nothing,” she says.

Arne Glimcher, dealer: It was difficult. There were only a handful of collectors: Vera List, [Emily and Burton] Tremaine, Howard Lipman, [Robert and Ethel] Scull. The general public didn’t like [the work], and the collecting world in general wasn’t interested in it. People would come into the gallery for Robert Irwin’s early shows, turn around and leave. Minimal art was much harder than Pop art [to sell] but there were those few collectors who collected everything, and they immediately bought what was new. You have no idea what it was like—every time we sold a painting, it was a miracle.

Michael Todd, artist: There was no market for my work. The Pace Gallery sold some of my [early] fetish sculptures, but I was never able to sell anything of Primary Structures-nature. I had a stipend from Pace Gallery and I taught at Bennington College for two years. One got by somehow. I sold a bit here and there—Philip Johnson bought one of my sculptures.

Primary Structures casts a long shadow. In 2014, the Jewish Museum staged Other Primary Structures, a two-part show that included many of the international artists left out of the first exhibition. It was both a homage and a critique, a reflection on the original show’s importance and a reassessment of its Anglo-American focus. But as early as the 1960s, artists such as Joseph Kosuth, with his cerebral, conceptual art, were extending and inverting Minimalist art—which, for some, was a travesty.

Peter Halley, artist: [Primary Structures] had something to do with the idea that we live in this super-fast era, in the 1960s. We’ve got to make it a red circle on a black background because that’s the kind of art that’s appropriate for this fast-paced world. We no longer live in a world where you can slow down and look at Morandi and Cézanne. I’m a true believer. I still make work like that with simple forms. As an artist, I come right out of those ideas.

Larry Bell: I’m not sure I ever came to the conclusion that [the show] was so influential. From my position, it was just an opportunity to do a show. I’m not an intellect and I’m not very articulate. Maybe I’m better than I was, but I still don’t have a lot of the art history in my brain. If you tell me it was that influential, I guess it was.

Carl Andre: There are still Minimal artists churning out their work—the ones still alive, anyway. Unfortunately, I think there was one consequence of Minimal art that was disastrous. People thought: “OK, so why even use materials at all? We just have an idea.” The Conceptualists, and I knew some of them very well, were showing ideas, and I told them that you can’t have art as an idea. Art must have some material presence. Ideas are not art.