Tori Wrånes: Drastic Pants, Carl Freedman Gallery (until 2 April)

Not only a terrific title but also an unforgettable first UK solo show by this Norwegian artist, who is already making big waves on the international scene with her very particular brand of dreamily dark performances that use the abstract sound of her voice plus prosthetic makeup and bizarre props.

At Performa, for example, she dangled upside down with an extra pair of legs, while those visiting the Sydney Biennial were treated to the sight of her singing beneath a giant and perilously swinging rock, using a microphone that doubled as a phallic tail.

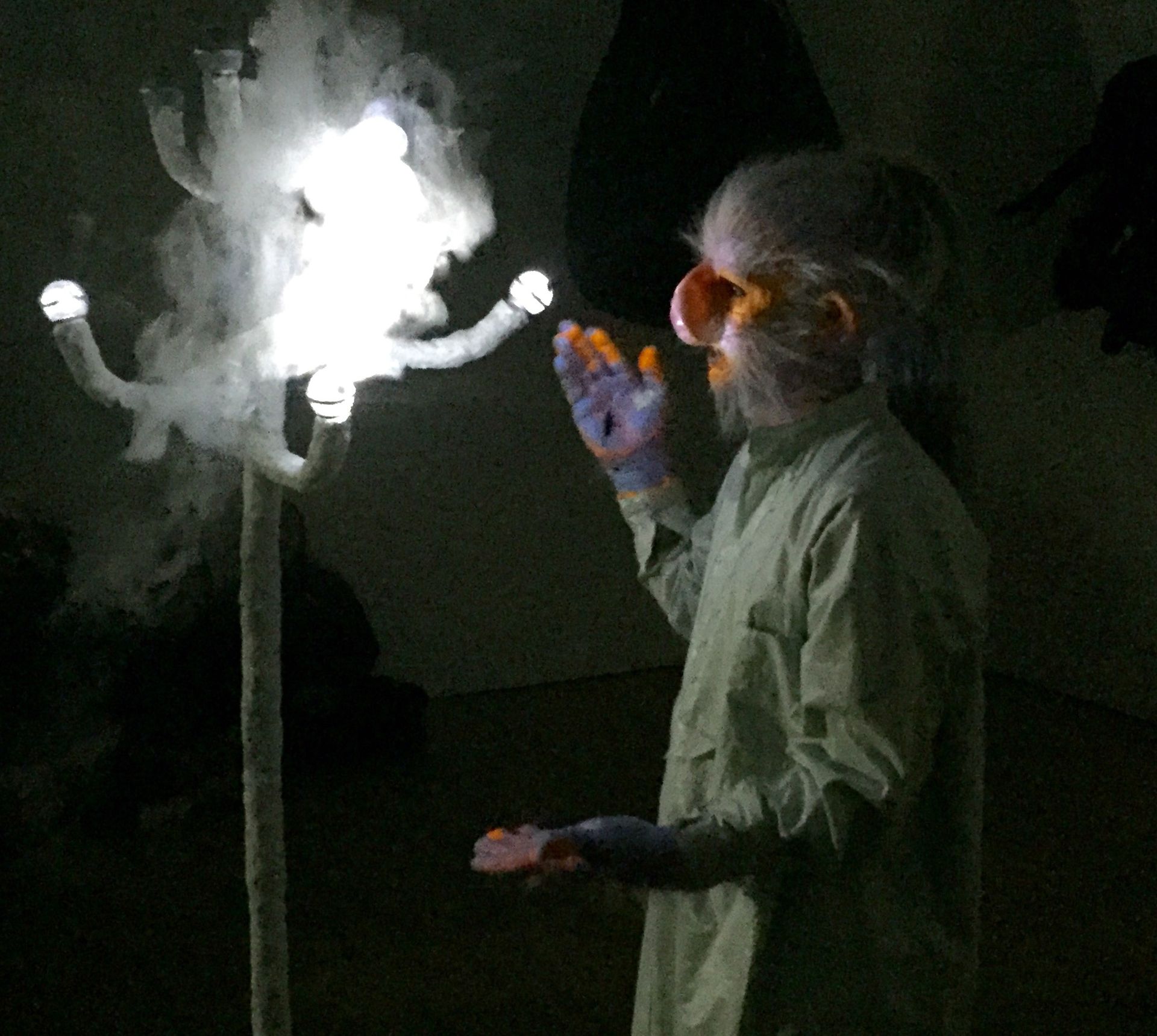

For the one-off live piece at the opening of the Freedman show, Wrånes mutated into an ancient, grey-bearded, troll-like persona, who emerged from the gloom of the darkened gallery to make strangely melodic squealing, growling and groaning sounds into a multi-headed microphone that not only lit up at the end of each of its six branches but also belched smoke.

The craggy branched microphone remains one of the exhibits in a show that, although no longer inhabited by the artist, is nonetheless animated by a strong, uncannily physical presence. Stiffened with silicone, a white cotton tracksuit and black leather jumpsuit spring to life, climb the walls and strike elaborate poses; while three beanbags, painted with prosthetic makeup, dangle and slowly rotate like boxer’s punchbags. Then there are the vivid, claggy little abstracts made from prosthetic paint and a tiny gold cross that slowly twirls on a wall-mounted framed slab of marble.

Throughout, Wrånes weaves together the most banal of components to create an environment where you feel anything could unfold.

Joe Spence: the Final Project, Richard Saltoun (until 25 March)

In 1991-92 the British artist Jo Spence was diagnosed with leukaemia. It triggered a body of work she described as The Final Project, which occupied her for the final two years of her life. Elements from the project have now been sel ected for this poignant, harrowing and at times savagely irreverent show.

As Spence adjusted to her approaching death and her increasing physical debilitation, she worked to express what she described as “the crisis of representation I’m passing through”. Feeling an increasing mismatch between the physical appearance of her rapidly weakening body and her mental state, she not only recorded her own appearance, but also adopted a more allegorical approach.

Often she looked to cultures that have embraced death as an inevitable feature of life, most notably Mexico’s Day of the Dead cult. She made her own shrines and still lifes, positioning joke-shop masks and plastic skeletons in macabre and often mordantly humorous scenarios. She also mirrored her own sense of physical disintegration in a series of richly textured, crumbling self-portraits, which in a pre-Photoshop era she created by exposing two images on top of each other in a “slide sandwich”.

“How do you make leukaemia visible? Well, how do you? It’s an impossibility,” she declared. But out of her fear and frustration this exceptional artist faced down death and disease in ways that continue to be inspirational on both an artistic as well as a personal level today.

In the Age of Giorgione, Royal Academy of Arts (until 5 June)

This utter gem of a show provides the most comprehensive UK viewing to date of Giorgione, one of the most enigmatic and intriguing figures of the Venetian Renaissance, who died from the plague at the age of 32.

Only a handful of works are concretely attributed to the artist, described by the great Renaissance scholar Bernard Berenson as a “shadowy, fluctuating, half-mythical figure”, and many are here, along with works by Titian, Bellini and other key figures of the early 16th century, who we see here ushering in the golden age of Venetian painting.

Right from the start we see that Giorgione was something special. The unknown young man in a pink shirt that is the subject of Giorgione’s earliest portrait—painted when the artist was still in his teens—rests his arm on a parapet and meets your gaze in a way that is infinitely more psychologically complex and engaging than the aloof head by the reigning elder statesman Giovanni Bellini that hangs opposite. Equally, the fleshy eye-contact immediacy of Giorgione’s slightly later Terris Portrait has so much more human impact than the two meticulously detailed but infinitely less animated portraits by the Venetian visitor Albrecht Dürer that flank it.

It was Giorgione who reclaimed the landscape as a rich and viable subject. Although his Tempest remains in the Accademia in Venice, we are given the National Gallery’s exquisite and mysterious Il Tramonto as compensation. Astonishingly, the Accademia did agree to lend one of Giorgione’s most radical works, La Vecchia, his intense and compassionate study of a woman in old age, here on show in the UK for the first time. Repeatedly Giorgione broke new ground with his subtlety, vivacity and bravura technique in ways that were keenly noted by his slightly younger friend Titian, who outlived and ultimately eclipsed him.

As well as giving new insight into the work of Giorgione, this show provides a compelling snapshot of La Serenissima on the cusp of her cultural heyday. We see how the combination of civic wealth and power with the constant threat of war and plague gave rise to a febrile sense of the fragility of life. It is something Giorgione was brilliantly adept at capturing and which makes his paintings especially apposite more than half a millennium later.

Mark Wallinger: ID, Hauser & Wirth (until 7 May)

Freud and psychoanalysis permeate this latest manifestation of Mark Wallinger’s ongoing artistic investigation into identity and the power structures that control who and what we are—or think we are.

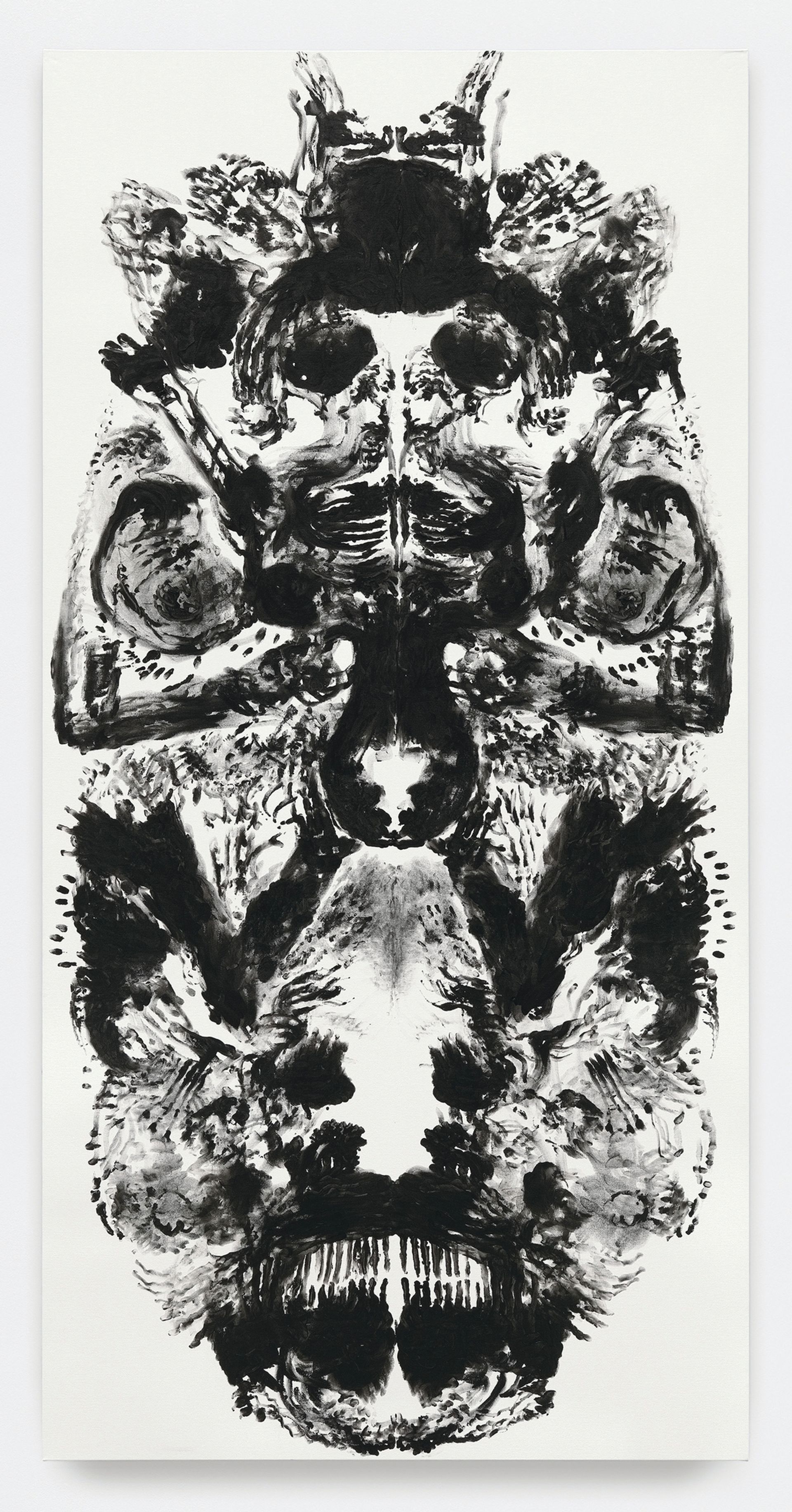

The most dramatic element of Wallinger’s Hauser & Wirth debut is the room full of 17 striking new black-on-white “id” paintings. They look like giant Rorschach blots, but have in fact been dabbled, scrabbled, stroked and fingered into existence by the artist’s bare hands. Measuring exactly double Wallinger’s height and the width of his arm span, this new bodily body of work taps deeply into the artist’s Freudian underbelly and—as we bring our own baggage to their suggestive shapes—also our own.

Personal and other forms of scrutiny are given a markedly different expression in Superego, a tall, mirrored sculpture that takes the form of the famous triangular sign that revolves outside New Scotland Yard. The hands of Wallinger are again very much in evidence in Ego, a deceptively simple photo piece in which he snaps his mitts in Michelangelo-mode, recreating the God creating Adam gesture from the Sistine Chapel and then printing the result onto a couple of sheets of paper pinned to the wall.

Throughout this characteristically rich and multi-referential show, Wallinger is omnipresent but elusive. He films his shadow walking, dipping and diving through the streets of London in a 21st-century take on the artist as flâneur. And in another four-screen video, an oak tree on a traffic island changes according to the seasons, filmed by the artist using an iPhone Blu-Tacked to his car window while he circumnavigates the Essex roundabout where he learned to drive. In every instance the work is highly personal to Wallinger while at the same time providing multiple points of entry for us all.