Asian export art The trade in Asian export art is catching up with its global roots. The continent-crossing field—ceramics, textiles, furniture and decorative objects produced in the Far East for export to the West between the early 15th and the mid-19th centuries—is now attracting collectors in its countries of origin. European and US collectors and museums have been active in the market for years, but the past decade has seen buyers emerge in Brazil, the Middle East and “especially in Asia”, says the dealer Jorge Welsh, who is on Tefaf’s vetting committee.

Chinese collectors in particular are turning their attention from porcelain made for the domestic market—where prices “shot up dramatically”—to the luxury wares that got away. “There are not tens but hundreds of museums opening in China, and quite a few of them are interested in Chinese export porcelain,” Welsh says. He is bringing a late 18th-century eight-tier porcelain pagoda, of the kind once commissioned by European royals, to Tefaf this year.

Although a host of recent museum exhibitions is testament to thriving scholarship, proposed US legislation restricting the ivory trade may have an impact on acquisitions. “Some of the most important acquisitions we’ve made in the past 15 years have been either entirely ivory or incorporating elements of ivory,” says Karina Corrigan, the curator of Asian export art at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. “That’s not something I would undertake—certainly not acquiring abroad—any more.”

Delftware Tefaf is home territory for Dutch delftware—blue-and-white pottery that was originally made by Delft’s potters to compete with the influx of Chinese porcelain flooding the European market from the early 1600s. Yet despite the appearance of delft on ten to 15 stands this year, the sole specialist is Robert Aronson. Although the market is still largely in northern Europe, Aronson says that interest has broadened in the past two years across the US, Europe, Dubai, Hong Kong and Australia. Particularly active is the Hague’s Gemeentemuseum, which is investigating the possibility of establishing a new museum in the city, dedicated to the institution’s extensive delftware collection, which would be the first of its kind.

The European ceramics expert Errol Manners, who is on the vetting committee for Tefaf, describes the 17th century as the great age of Dutch delftware. “Its development in the first half of the century is a fascinating study for academic collectors, but it is really the blue-and-white products of the last quarter, when it becomes an art form patronised by royalty, that are in great demand,” he says.

Pieces commissioned by the UK and Dutch royals William and Mary for their palaces Het Loo and Hampton Court are the most highly prized, and the delftware of this period can often be quite Baroque, even architectural, in form.

Aronson says that bargains can still be found in the middle market, but that prices for top pieces are strong. He sold a monumental pair of late 17th-century tulipières (flower vases) to a British collector for just under $1m at the New York Winter Antiques Show in January.

Silver High quality guides the silver market at all price points, says the dealer Timo Koopman of London’s Koopman Rare Art. Collectors seek the best representation of a given type, regardless of chronology or geography. “You could spend £1,000 on a great nutmeg grater or many millions of pounds on a fantastic, best-of-the-best object, so the range is huge,” he says. Given silver’s history as a status symbol among monarchs and nobles, it is perhaps unsurprising that modern- day collectors have national loyalties. “Australians will look for Australian silver, the French for the French things,” Koopman says. “But English silver is probably the most international.”

At Tefaf, Koopman is showing a silver-gilt ewer with an elaborate frieze of sea creatures (£325,000) and a pair of wine coolers designed to resemble woven baskets (£250,000) by Paul Storr, the renowned 19th-century English silversmith. Neither featured in the gallery’s major Storr exhibition in October. The accompanying book, by the scholar Christopher Hartop, represents “probably the first literature in 50 years”, Koopman says.

Private collectors have also been “instrumental in promoting silver scholarship” through gifts and loans, says Tessa Murdoch, the deputy keeper of sculpture, metalwork, ceramics and glass at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London. The museum has displayed the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert collection of English and Continental gold and silver, mosaics and enamel portrait miniatures on long-term loan since 2009. It was able to acquire a silver cup and cover—a gift from King George II to mark his goddaughter’s christening—on behalf of the Gilbert Trust during Tefaf’s preview day in 2014, Murdoch says. This month, the V&A is sending almost 50 pieces of British silver from the Gilbert Collection to Hong Kong’s Liang Yi Museum on loan.

Egyptian antiquities Few areas of the market have become as politicised as antiquities, due to the increase in looting in the Middle East following the Arab Spring and the often sensationalised reports of the trade in “blood antiquities”. A proposed amendment to Germany’s cultural heritage laws, partly sparked by reports of looted objects going through the country, will affect the trade there, as major collections are already leaving Germany, says David Cahn, the Swiss dealer and head of Tefaf’s antiquities vetting committee. The draft legislation requires export licences for items more than 70 years old and worth more than €300,000. It also states that in the case of a legal dispute, owners must provide proof of provenance for the previous 20 years for any items of “archaeological value” worth €100 or more. But Cahn says that this will probably “have a greater effect on the Modern and contemporary markets” than on the antiquities market. “Looting has not affected the trade [in antiquities] between high-level dealers and collectors, for whom due diligence is fundamental,” he says.

With Egyptian antiquities, as with all ancient works, provenance is key and demand is still strong “for pieces with good provenance”, says Martin Clist, the managing director of the London-based gallery Charles Ede. The legal export of antiquities from Egypt ended in the mid-1980s, so reputable dealers will not touch a piece without receipts or photographs proving that it left Egypt before then.

In this consistently steady sector, high-quality pieces from the Old and New Kingdom are the most desirable, along with works from the late Ptolemaic dynasty, during which “the influence of Greek art had a transformative effect on traditional Egyptian iconography,” Clist says. Heads are particularly popular “because we feel an immediate rapport”, he says, adding that animals are also sought after.

The most notable (and contentious) sale of recent years was that of an Old Kingdom statue of the scribe Sekhemka from Northampton Museum and Art Gallery in the UK. The piece went for £15.8m (with premium)—an auction record for an Egyptian work—at Christie’s, London, in 2014. The museum’s decision to sell the statue to fund restoration projects was widely condemned. In November 2015, a monumental, granite, 18th-dynasty figure of the goddess Sekhmet from the Alfred Taubman collection sold at Sotheby’s, New York, for $4.2m (with premium)—a strong price for a depiction of the deity.

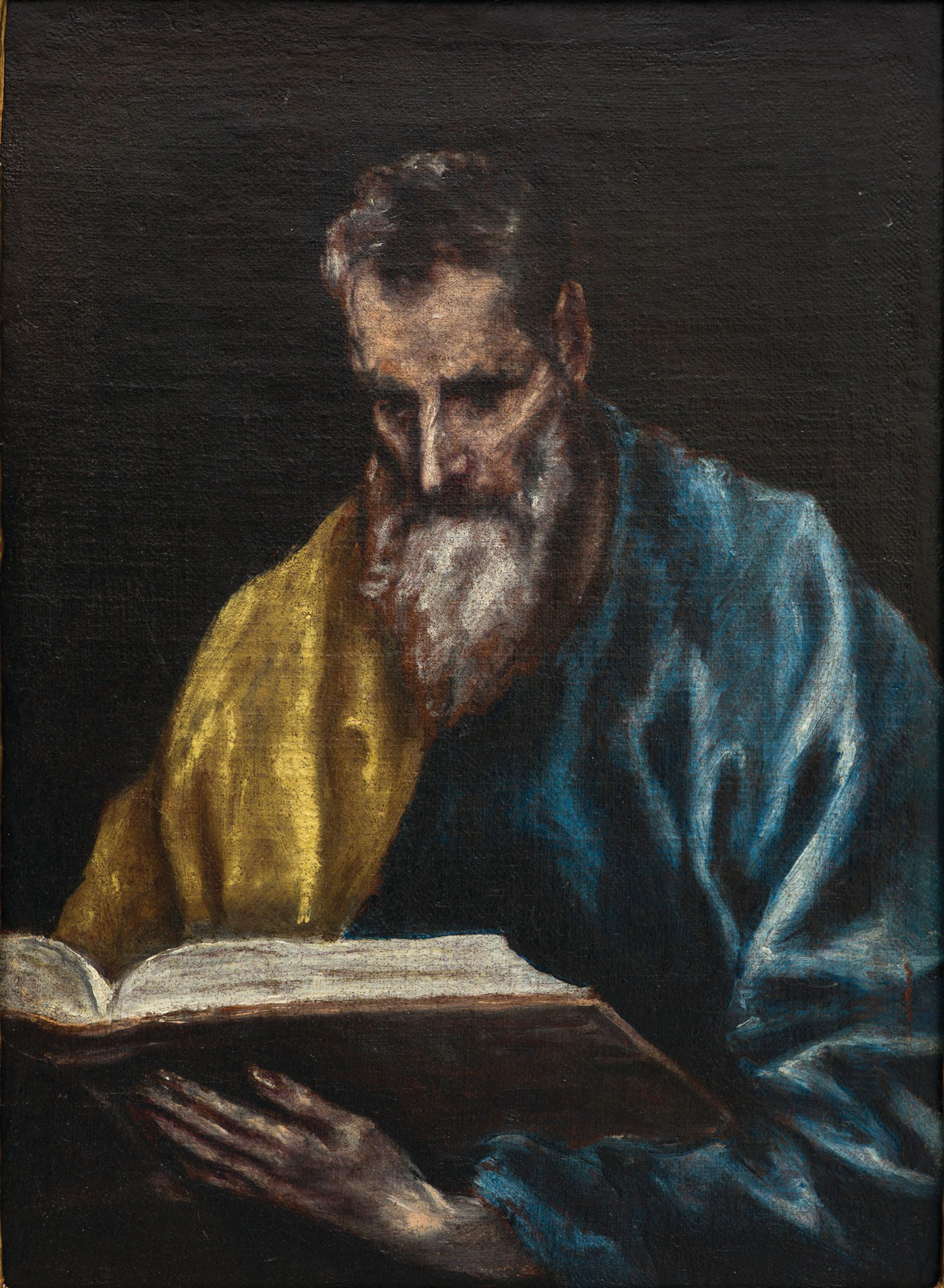

Spanish Old Master paintings Accepted wisdom within the Old Master trade is that the secular subject matter favoured by northern European artists is commercially easier to shift than the overtly religious southern European paintings. However, the shocking, often bloody, subjects found in the Spanish late Renaissance works of which collectors once steered clear are now attracting Modern and contemporary art buyers to the field, says the London-based dealer Derek Johns.

“There has been a groundswell of interest at the top end in the past 12 months,” says Johns, who specialises in Spanish paintings as well as Latin American viceregal ones—an area in which US museums are now beginning to collect.

The dealers Jorge Coll and Nicolás Cortés of Madrid’s Coll & Cortés, which recently merged with the 255-year-old London firm Colnaghi, say that Spanish and US museums (as well as international private collectors) are the key buyers in the field, but that the main market lies outside Spain. In 2012, the Spanish dealers sold Jusepe de Ribera’s The Tears of Saint Peter (around 1612) to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in what was reportedly the institution’s first purchase of a Spanish painting for 40 years.

El Greco, Velázquez and Goya are the undisputed celebrities in this sector, and as a result, their work is rarely available. The market-defining sale of El Greco’s Saint Dominic in Prayer (around 1605) for £9.1m (with premium) at Sotheby’s, London, in 2013 was an auction record for a Spanish Old Master. Works by Zurbarán, Ribera, Meléndez, Morales and Murillo are also in demand at an international level.

The 2009 exhibition The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600-1700 at London’s National Gallery was instrumental in sparking interest in Spanish Golden Age religious art. Since then, institutional shows of Spanish masters have proved popular, including the multi-venue show of works by El Greco that was staged in Spain, in 2014, to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the artist’s death. Elsewh ere, exhibitions on Goya in London and on Velázquez in Paris proved to be crowd-pleasers in 2015.

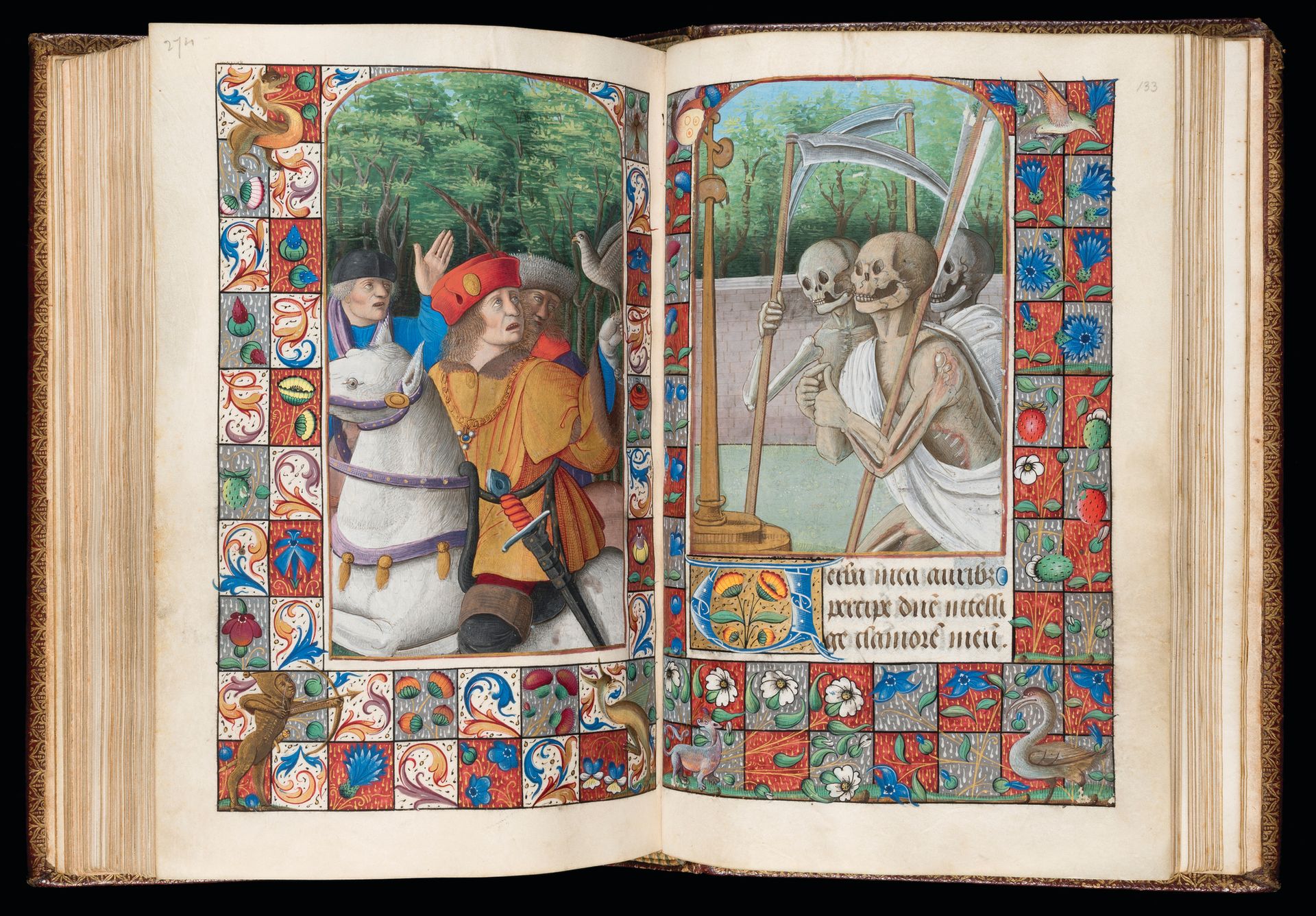

Illuminated Manuscripts Illuminated Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts comprise a “small but very Illuintense market”, says Roger Wieck, the department head at New York’s Morgan Library & Museum and a member of the Tefaf vetting committee. “The number of high-quality items continues to shrink, and that is reflected in the ever-increasing prices.”

The quality of a manuscript is not solely determined by its condition and beauty, although intact margins, undamaged miniatures and innovative iconography are all prized. “We still live in a culture where a firm attribution—that is, an artist’s name—would sway a buyer,” says Stella Panayotova, a Tefaf vetter and the keeper of manuscripts and printed books at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

The Swiss dealer Heribert Tenschert is bringing a rare rediscovery to Tefaf: an unfinished 15th-century Book of Hours with 30 unpainted drawings by one of the Limbourg brothers, the Dutch miniaturists whose Très Riches Heures, created for Jean, duc de Berry, is “perhaps the most famous manuscript in the world”, Wieck says.

Secular manuscripts are of particular interest to institutions. The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles recently bought a 1530s chronicle of the battle victories of a knight in the Order of the Golden Fleece for an undisclosed sum from Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books in Switzerland. The Book of the Deeds of Jacques de Lalaing, featuring a frontispiece by the leading Flemish illuminator Simon Bening and 17 miniatures by an anonymous painter in the circle of the Master of Charles V, is scheduled to go on public display for the first time in five centuries this summer.

French courtly love poetry is due to feature in the second auction from the library of the Alsatian tobacco magnate Maurice Burrus at Christie’s, London, on 25 May. The almost 40 manuscripts “have disappeared from view” since they entered Burrus’s collection in the 1920s and 1930s, says Kay Sutton, the senior specialist in Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts at Christie’s.

Sculpture Old Master sculpture can seem intimidating to the novice collector. Although prices are reasonable compared with the dizzy heights of contemporary art, “it needs a developed taste and knowledge to buy confidently in this market”, says Alexander Kader, the head of European sculpture and works of art at Sotheby’s.

Authenticating bronze casts, for example, is a minefield, as the process is inherently reproductive. Identifying the casting technique and analysing the metal alloy or traces of the clay core can help to distinguish a Renaissance bronze from a later copy but “science gets you only a certain way”, Kader says. In the absence of artists’ signatures or foundry marks, experts rely on connoisseurship to make attributions, but “a catalogue raisonné for most sculptors just doesn’t exist”.

The diversity of the field is also its strength. “When one area is down, another one is up,” Kader says. There is a growing appetite for Spanish sculpture, which “had been undervalued”, particularly the 17th-century polychrome wooden religious figures carved by Pedro de Mena and his circle.

In 19th-century and Modern sculpture, posthumous casting remains “a very thorny issue”, says Patrick Elliott, a senior curator at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and a member of the Tefaf vetting committee. “Collectors are often surprised to find that Brancusi, Giacometti, Rodin and so on are still being cast, years after their deaths, and that it’s all perfectly legal,” he says. Tefaf accepts only lifetime casts of 19th-century sculptures and imposes strict rules on posthumous editions of 20th- century and contemporary works.

Interest in Rodin’s sculptures looks set to continue in the run-up to the centenary of his death in 2017. Certificates of authenticity issued by the Paris-based Comité Rodin have clarified the market, helping prices to triple in the past decade, says the dealer Robert Bowman. In a recent sale at Sotheby’s, a rare lifetime cast of Iris, Messenger of the Gods (1890-91, cast 1902-05) fetched £11.6m (with premium), a new auction record for a Rodin sculpture. It previously sold at Sotheby’s, in 2007, for a then record £4.6m. But perhaps more significant is the £782,500 achieved at Christie’s last month for a 1970 cast of The Kiss, authorised by the Musée Rodin in Paris. “It shows that posthumous casts of Rodin’s work are now accepted by the art market and highly valued,” Bowman says.

18th-century French furniture Previously strong buying from the US never fully recovered after 9/11, and several Paris- based furniture dealers are feeling the lingering ripple effect. The former Tefaf exhibitor Pelham Galleries of Paris and London is due to sell pieces from its stock and private collection at Sotheby’s, London, on 8 March, because the firm is shifting its focus from furniture and works of art to antique musical instruments.

Marella Rossi of Galerie Aveline in Paris sees a light at the end of the tunnel. “The market for French 18th-century furniture has been struggling, but in the past couple of years, there has been an upsurge in interest among younger buyers who want to inject spirit into their interiors,” she says.

Exceptional pieces by key ébenistes (cabinet-makers) such as Philippe-Claude Montigny and André-Charles Boulle are still in demand. In November 2015, Christie’s in Paris sold an early Louis XVI ormolu-mounted ebony desk and two inkstands by Montigny for €2.2m (with premium)—an auction record for the maker.

There was tentative buying from Chinese collectors at the height of their buying boom in around 2012. Christopher Payne, who sits on Tefaf’s vetting committee, gave a series of lectures on French furniture aimed at wealthy individuals in China, and in 2015, Hong Kong’s Liang Yi Museum staged Great Minds Think Alike: 18th-Century French and Chinese Furniture Design. Organised with the Parisian dealer Mikaël Kraemer, the show placed the museum’s Imperial Chinese furniture alongside 18th-century French pieces. Although China’s economic slowdown has had an impact, Payne says his contacts are cautiously confident.