It’s 40 years since the Canadian dealer Donald Ellis founded his gallery dedicated to Native American art in New York. The leader in this highly specialist field, Ellis has sold pieces to most of the prominent institutions in the United States, as well as to representatives of the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, and the Louvre in Abu Dhabi.

Ahead of showing at the Armory Show in New York (3-6 March 2016), he talks to The Art Newspaper about why his area deserves more attention—and how the “religion” that is contemporary art isn’t helping anyone.

The Art Newspaper: How did you become interested in historic Native American art?

Donald Ellis: I started to collect when I was about seven years old – things that I could literally find such as arrowheads and pottery shards. Initially, my interest was more in the culture of Native Americans and through that I became fascinated in the art. When I was in my 20s, I became aware that [historic] African art was accepted in the larger art market, yet my field was not. I strongly believed that the very best Native American art could stand next to the best African art; to any art for that matter.

What are the biggest challenges facing your field?

One of the challenges is the endless misinterpretation in the media of the Native American Graves Protection Act [a 1990 law that requires the return of Native American cultural items to descendants]. This act relates only to federally funded institutions in the United States. Neither private collectors nor Parisian auctioneers are affected.

We also suffer from having very little curatorial and institutional support. An exception to this was the superb exhibition of Plains Indian art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art last year [Artists of Earth and Sky, 2015]. It was a huge critical and commercial success.

Perhaps the biggest challenge we, and others, face is this new religion called contemporary art. It seems to suck the oxygen out of everything else, not just in my field. It often seems that the only conversation is the contemporary art conversation.

Are there common misconceptions about historic North American art?

I would say the biggest misconception is that the Native American market is all feather war bonnets and tomahawks, beadwork and Navajo jewellery. The decorative market dominates and, unfortunately, there are not enough dealers at the high end to educate and expose the more important works of art to the public.

Which pieces are the most popular in the collector market?

At the high end, masks from the northwest coast and Yup’ik [Alaska] peoples are popular, and command the biggest prices, alongside classic 19th-century Navajo textiles.

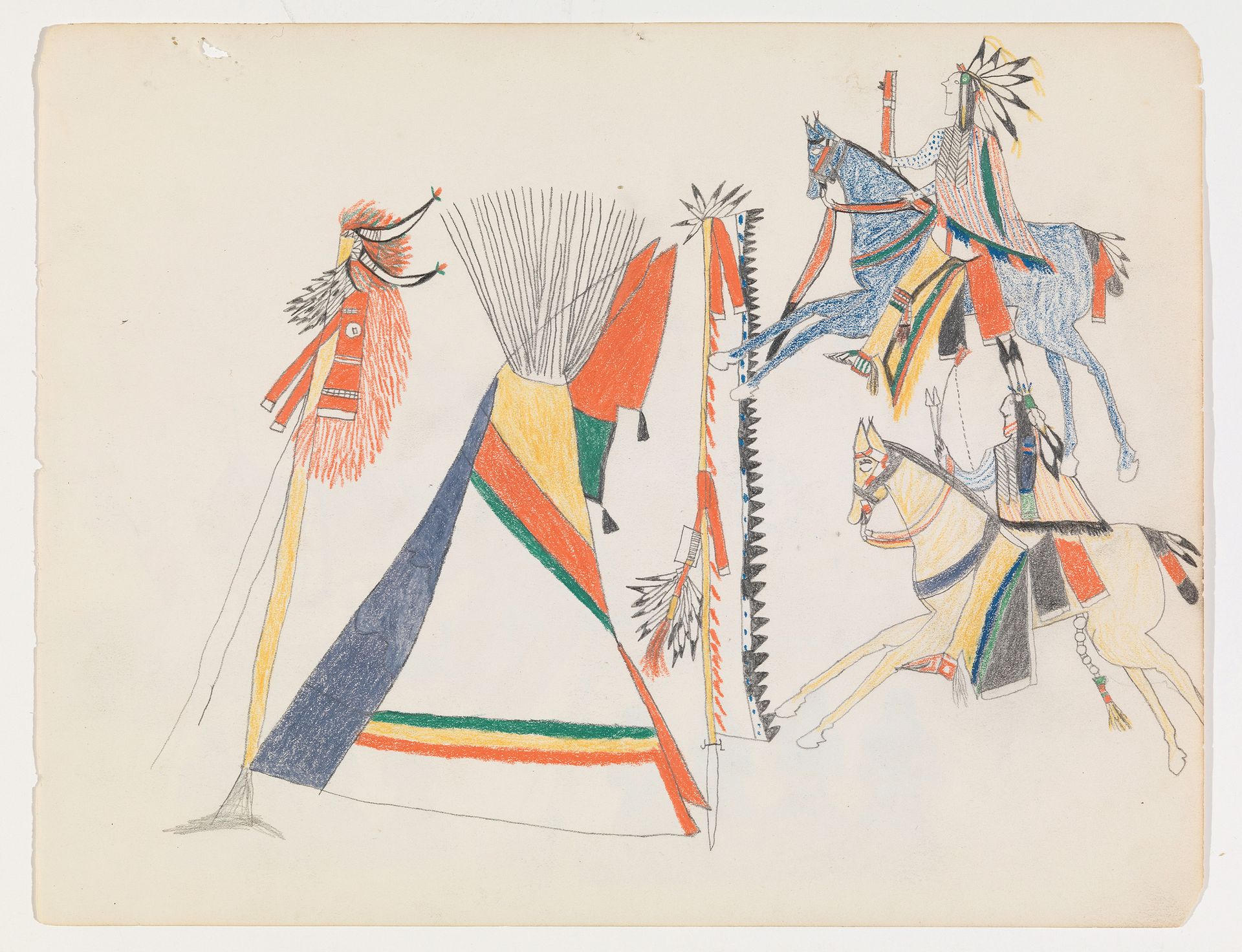

We exhibited Plains Indian ledger drawings (1865-1900) at Frieze Masters in London in 2014 and I have never, in 40 years of trade, seen such enormous interest and excitement. They are rare, but I have tried to buy every one I could over the past 20 years. They are an extraordinary record of time and place, and an incredibly important aspect of American art history, of which very few people are even aware.

Do you think the African art market overshadows your market?

Prices achieved at auction and in private sales in the African and Oceanic market vastly outperform the Native American market, so in that sense, yes, absolutely. The great dealer and philanthropist Eugene Thaw, who helped establish this field when he started to collect in the 1980s, once told me that if I wanted to further my market, prices had to be substantially increased.

Five works of art have sold for more than $1m at auction in my field since I began. This can frequently happen in a single Tribal art sale in Paris, which is an astonishing statistic. On the plus side, it costs me less to have a large inventory of important works—and for collectors, the field is much more affordable.

What is the most expensive work of art you’ve sold?

The gallery sold an extraordinary Yup’ik mask for $3.8m in 2012, which, to my knowledge, still stands as a record price in this field.

What is behind the price disparity in your field compared to the African and Oceanic markets?

I have struggled with this for decades. An obvious answer would be because the Picasso/Cubist connection carries more cultural currency than the Breton/Surrealist interest. Few people outside of art history academia are aware of the enormous influence that Native American art had on 20th-century artists, from the Surrealists to the Abstract Expressionists. Jackson Pollock visited the landmark 1941 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art [New York], where Native American art was first exhibited outside of an ethnographical context. There is a relationship between his drip paintings and the Navajo sand paintings that he discovered there. Barnett Newman curated a show of Northwest coast art at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1946. Andy Warhol and Donald Judd also collected in this field.

What I find surprising is that North America has the highest concentration of art collectors in the world, but very few are interested in the first art produced in their country.

Are most of your clients from North America? If so, which parts?

My client base in North America is quite evenly split between Canada and the US. We exhibited overseas for the first time four years ago and since then we have steadily increased our European base, most notably in France. The French have a deep interest in “primitive art”. In [Frieze Masters] London in October we also sold to buyers from Switzerland, Belgium, Germany and the Middle East, almost entirely to new clients.

Do you get a lot of cross-collectors? What advice would you give to someone keen to begin collecting in this area?

Only a handful of my clients solely collect historic Native American art. Most are serious collectors of Modern, post-war and contemporary art. For someone new to the field, most of the standard recommendations apply. Educate yourself, read the literature, develop a relationship with a dealer or advisor whom you trust and, most importantly, look. You can develop a strong visual database through museums, books, exhibitions and catalogues. Then be patient and always choose quality over quantity.

Do you collect? If so, what?

I do collect, although not in my field. I was taught by a mentor a long time ago that collecting in your own area of dealing puts you into competition with your clients, which is not healthy. My own collecting tends to develop around a new discovery, which usually lasts for about five years when I sell or donate. Some of my past interests include Ainu textiles, 19th-century photography relating to Native Americans, neolithic Japanese pottery, and 17th- and 18th-century Negoro [medieval Japan] lacquerware. I am currently collecting contemporary First Nations photography.

How important are art fairs to your business?

Art fairs are increasingly important to us. As a private dealer, not having an open gallery space, it has become the primary way of meeting new clients, along with curating exhibitions at contemporary art galleries. I find the Frieze Masters and Tefaf Maastricht formula the most interesting, and I think most other collectors do also.

Where do you see the future of this field going?

We are experiencing a number of the issues that are affecting most other fields, notably the difficulty of a steady supply of important works. Presently, several of the most prominent collectors are of an age where they are slowing down. There is an opportunity for a new collector to establish themselves quickly. You could build an extraordinary group of significant works of art in this field for the price of a single mid-level Impressionist painting. I am feeling optimistic. Things seem ripe with possibility at the moment.

• Ellis is organising an exhibition of Plains Indian ledger drawings at Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, which opens on 3 June 2016.