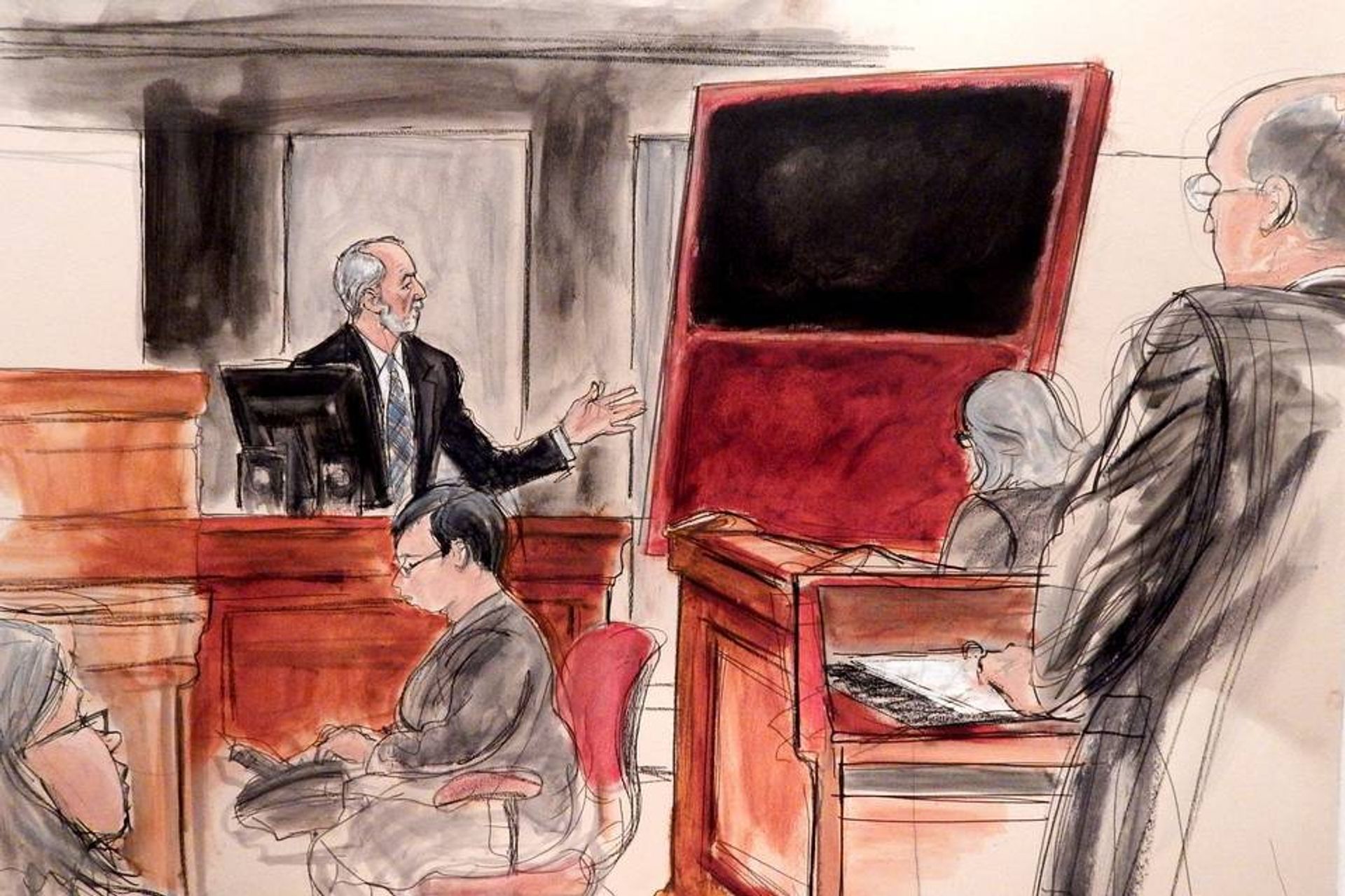

The Knoedler gallery, which had a blue-chip reputation that helped it sell almost $70m of Abstract Expressionist fakes, depended on the forgeries to stay afloat during its last decade-and- a-half. That was the testimony of the forensic accountant Roger Siefert in the two-and-a-half-week trial that abruptly ended in February when the Sotheby’s chair Domenico De Sole and his wife Eleanore reached a settlement with the former Knoedler director Ann Freedman, the Knoedler gallery and its owner, 8-31 Holdings.

The De Soles sought $25m, alleging Freedman and Knoedler knowingly sold them a counterfeit Mark Rothko, an accusation the gallery and its former director deny. Freedman’s lawyer Luke Nikas told the jury in his opening statement that she “believed it was the most important discovery in art history”. The terms of the settlement were not disclosed.

The trial ended soon after Siefert’s testimony, so the art world never heard Freedman give her account in court, including why she thought a trove of 40 fakes from Long Island-based art dealer Glafira Rosales was genuine. Siefert had lifted the veil on Knoedler’s precarious financial state and Freedman’s gain from selling the forgeries on a Friday two weeks into the trial. By Sunday night, Freedman and the De Soles had settled.

Siefert analysed Knoedler’s finances from 1994, when the first of 40 fakes was brought to Knoedler by Rosales, until 2011, when Knoedler closed amid allegations it had sold fakes. Siefert said: “Knoedler would not have been profitable without the sale of the Rosales works” and would have suffered a $3.2m loss. Freedman got $10.4m as her share of the profits on the fakes in addition to her average yearly salary of $300,000, Siefert said.

Two days later, Knoedler and 8-31 Holdings also settled after the gallery’s chief financial officer, Ruth Blankschen, testified, revealing its questionable handling of money. For example, Knoedler paid Rosales partly in cash, Blankschen said. Cash payments are a widely acknowledged way of hiding income from tax authorities; Rosales pleaded guilty to federal charges of tax evasion and money laundering in 2013.

The jury heard evidence that Knoedler and Freedman should have known that they were selling fakes: Rosales offered purported masterworks at below-market prices (Knoedler’s markup on the De Soles’ painting was 773%); the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) concluded it could not consider a purported Jackson Pollock from Rosales authentic. IFAR also said that the provenance Knoedler submitted was “inconceivable” and the provenance was then changed; Knoedler could not find a single document relating to any Rosales painting. Faced with these red flags, Martha Parrish, an expert in gallery practice who helped draft the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) code of ethics, testified that a “reputable dealer would have run like hell”.

One of the De Soles’ lawyers, Aaron Crowell, also elicited testimony from Blankschen apparently intended to show that 8-31 Holdings owner Michael Hammer treated Knoedler and the Hammer Galleries, another 8-31 subsidiary, as his personal piggybank. For example, when he wanted to buy company cars, money was taken from whichever bank account had funds—including $482,000 for a Rolls-Royce and $520,000 for a Mercedes, according to Blankschen. Hammer’s wife, who was not an employee of Knoedler or 8-31, had an American Express card in Knoedler’s name and charged a $10,000 trip to Paris on it, and Hammer himself took a yearly salary of $400,000, Blankschen said.

Who said what during the $25m Knoedler trial

The Rosales works

In pretrial testimony that the jury saw on videotape, E.A. Carmean, a researcher for Knoedler who is a former curator at the National Gallery of Art (NGA), Washington, DC, said that despite having “never found” a document supporting a provenance, he believed the Glafira Rosales’s works were authentic. “Your eyes can’t lie to you,” he said.

The “Rothko”

Domenico De Sole, the chairman of Sotheby’s and Tom Ford International, said: “I went to the best gallery. Ann Freedman had an amazing reputation… I had no reason to believe I wasn’t being careful. I asked Ann Freedman to put it in writing and she did, and that was the end of it.”

Dana Cranmer of Cranmer Art Conservation and a former Mark Rothko Foundation conservator, examined the De Soles’ Rothko for Knoedler. She said: “It didn’t seem like a forgery to me.”

Laili Nasr, the project manager, catalogue raisonné of Rothko works on paper and curator at the NGA, wrote to Freedman in 2002 saying that if the NGA published a supplement to the Rothko catalogue raisonné, it intended to include the De Soles’ Rothko. Nasr said: “Everyone had full trust in Knoedler and Ann Freedman”.

Christopher Rothko, the son of Mark Rothko, said: “I don’t get involved in questions of authenticity.” He was one of 11 names on a list given to the De Soles by Knoedler of experts who had viewed the fake Rothko.

David Anfam, the author of the Rothko catalogue raisonné, wrote to Jack Flam, the art historian and president of the Dedalus Foundation, in 2008: “It truly strains… credibility to suppose [paintings by so many different artists] could alike issue from a hand… other than that of the artists themselves.” He testified that he never saw the De Soles’ Rothko.

The “Diebenkorns”

John Elderfield, the former chief curator at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, told Freedman in 1994 that the Richard Diebenkorns from Rosales “were very dubious”.

Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, Diebenkorn’s daughter, told Ann Freedman in 1994 that works attributed to her father “don’t look right, there was no provenance”.

The “Pollock”

Sharon Flescher, the executive director of the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR), wrote in a 2003 report on a purported Jackson Pollock that the provenance Knoedler provided was “inconceivable” and IFAR could not conclude that the painting was authentic.

The “Motherwells”

Jack Flam, the president of the Dedalus Foundation, which maintains the Robert Motherwell catalogue raisonné, told Freedman in December 2007: “We believed [the Rosales Motherwells] were not authentic.”

James Martin, a forensic conservator at Orion Analytical, in 2008 concluded that two purported Motherwells had materials “inconsistent” with when the paintings were supposedly created. Knoedler “asked me to delete many of the most relevant conclusions”, he said.