New York is a trap. An art exhibition claiming to show its breadth is a fool’s errand. You only ever see one part of a network, one level of a system. The task of representing this network through artists and their work is fraught. An exhibition with such ambition is a fanciful, essentially corrupt menagerie, useful for propelling one grand myth so we might cope with the collapse of all the others.

In New York the system in question is a market—a market replete with history, but a market all the same. We’re not just talking prices. The market has broadened out from works of art to include MFA students, institutional shows, social circles and attention spans. It’s all the more knotty since its heyday passed; since the Club at 8th street closed, since Specific Objects was published and since Bushwick waned. Enter history into the equation, and, well, you’ve been warned. If Greater New York succeeds, it is as a faithful but incomplete account of a city that is still a lodestar despite considerable wear.

This year, the curatorial team, led by Peter Eeley, strives to connect the relentless push for novelty with a perceived nostalgia for the 1970s and 1980s. Much of Greater New York turns on the assumption that the work of its younger artists is rooted in the history of New York. It is a bold and enviable thesis, one produced less by art history than by the peculiar mendacity of curating. The assumption that nostalgia is a connecting thread is especially fraught when coupled with the accelerated pace of digital life, the now ubiquitous curatorial fodder that we hear about in the exhibition’s introductory text. But one of the singular developments to come from digital media is the way it introduces a type of amnesia. While it provides an archive, it also fosters a type of ahistorical practice that apes the tactics of past avant-gardes while evacuating their historical content. A younger artist's desire to resurrect socio-political change amounts to a media operation. Squaring this apparent contradiction is the aim of Greater New York, and it is through its dogged pursuit that the show unravels and underwhelms.

Greater New York is always turning this about, reconciling across generations, room after room. Does Eva Hesse lurk in Eric Mack’s Claudine (2014)? The work appears to have the same bone to pick with the cool formalism of the 1960s. Stewart Uoo might channel something from Jimmy DeSana’s photographic compositions, which are shown here as paragons of the freewheeling 1980s East Village scene. Greg Parma Smith’s origami paper and pencils are served up alongside Robert Kushner’s Pattern and Decoration works. All have links both in form and substance. But the late Modernist masters, though they no doubt formed the institutional foundations on which young artists have grown, have never seemed so far away.

Greater New York is right in one sense: many of the artists who were born in 1980s will talk a big game online, but still fall asleep thumbing dog-eared pages of October. Fast forward to the exhibition’s pièce de résistance: two massive Louise Lawler installation shots, both rather recent examples of her famous works documenting the secondary presentations of Modern masterpieces. Stretched and manipulated, they dominate the museum’s largest room. They are an arresting reminder of the foundational critical tropes of “the contemporary.” And yet today, young artists update them like so much legacy technology. Lawler's generation focused on the way that art circulated through replication and commodification, but it only offered a peek at networked capitalism. Today's artists are left to pick through the remains of that network. Seth Price’s calendar paintings might seem to make the same gesture as Lawler and other Pictures Generation luminaries. But it’s a new network. New York is now much less speculative, more heavily administered, more material and increasingly swayed by the frenetic motion of international capital.

Greater New York is emblematic of theses tensions. We all look to the parables upon which the city was built, yet we are tasked with constant renewal and subversion. In the exhibition, there are difficult, tendentious connections that keep calling you back. Perhaps it is best typified by James Nares’ film pendulum (1976), in which a dizzying wrecking ball swings through a Tribeca alley. Or Alvin Baltrop’s series of photographs depicting the dilapidated West Side docks, once host to semi-public gay sex. These works are spectral—those docks and their inhabitants are gone and Tribeca is gilded. But both captured a fanciful would-be arcadia ultimately consumed by tragedy.

The New York of the 1970s seemed right on the cusp of imperial decline. It fits the familiar trope: a calm before the impending storm. What consumed the metropolis wasn’t urban decay as much as it was private enterprise run amok, the material remains of which are in the rooms given to Ben Thorp Brown and Cameron Rowland. Brown’s work Toymakers (2014) is a fly-on-the-wall video of labourers inside the Canadian factory that makes paperweight-like figurines that real estate developers use to commemorate transactions. Known as “Deal Toys” they lay somewh ere between custom art object and mass-produced commodity. Toymakers is a reminder that despite all the lip service, the rewards for massive financial transaction disproportionately benefits a small groups of actors.

Rowland’s installations target the Clinton-era assault on welfare, a staple of free-market ideology smuggled through the language of entrepreneurship. Rowland includes several objects found in small businesses—bodegas, liquor stores—that often spring up in neighborhoods largely dependent on government assistance. One work includes the bullet-proof glass thresholds used in shops where every consumer is treated as a potential threat. Here, they are solitary reminders of capitalism’s requirements for exchange and transparency in an economy where the perception of risk, and it requisite preemptive punishment, fall disproportionately on the poor.

Several other rooms are meditations on the New York’s peculiar material facts. Adam McEwen treats us to the banal with a reproduction of steel floor plate on aluminum. In his project Doors (1975–1976), Roy Colmer photographed every entryway for several city blocks. What started out as a serialized conceptual gesture has a perhaps unintended document of nostalgia for Old New York.

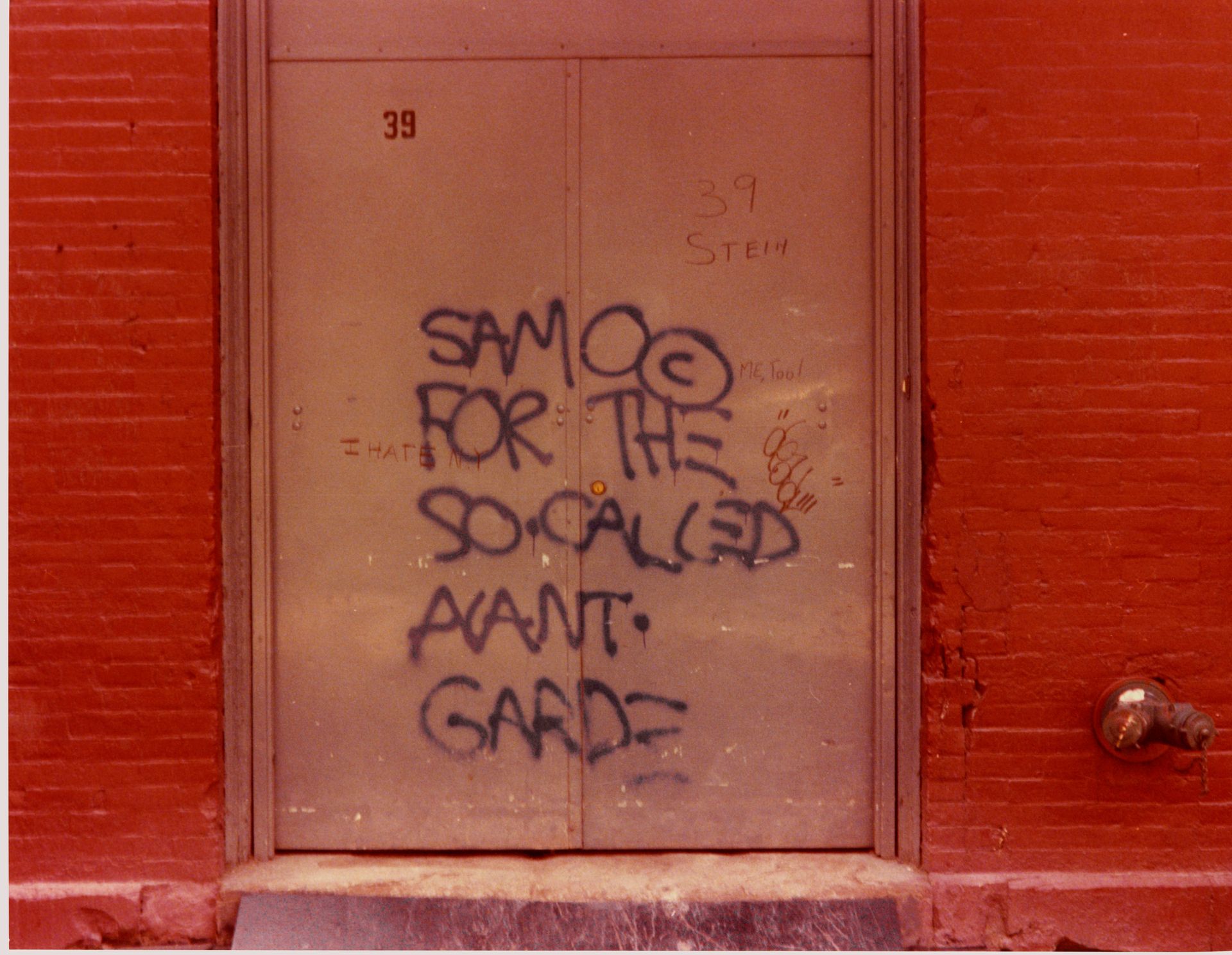

This history, like New York, can swallow you. Walking through the exhibition, you realise how often we throw young artists back into a mythical world that never existed. Whatever nostalgia exists for the 1970s operates mostly at a libidinal level. The starkest generational fault lines that manifest in Greater New York are among the older artists who still evince a faith in counter-culture and those younger artists for whom such a notion is largely disproved. There is a room dominated by Henry Flynt’s photographs of graffiti tags of the street art collective SAMO. But in an environment in which graffiti and street art are a laughable tool of gentrification, the most radical kids are wearing Nikes. Clothing from the Eckhaus Latta’s line fills a side hallway, poised to adorn a new generation that’s so hip to the mainstreaming of difference that they give up altogether. Deconstruction left the gallery for the runway, and now it’s back again.

It wouldn’t be a show about New York without housing woes. Nick Relph captures the skyscrapers of “Billionaire’s Row” in photographs—slapdash images that share a conceptual lineage with Sherrie Levine and Gordon Matta-Clark. Liene Bosque's miniature souvenir landmarks from cities around the world, Recollection (2000-2015), arranged on a tabletop, are buxom and playful but nonetheless make sense in their appeal to the vulgarities of the real estate imaginary. Ten texts by Glenn Ligon recount his various New York addresses. They evoke a journey underscored by displacement. Jamian Juliano-Villlan’s Better Times (2015) tells it straight: “FINALLY” “FOUND A PLACE” “WE COULD AFFORD.”

A cousin of nostalgia is romance. At PS1, it is elegiac and sentimental. Greater New York is, then, also something of an admission that New York got knocked down. Today, we know this town is little more than a stop along a larger network. Ever since you could attach installation images to an email, people have been waiting for the other shoe to drop. The exodus from the city, some said, would continue when the cost of living rose beyond reason, when the collectors went global, and when the art fairs grew into an agile commercial force that bypassed New York's fixity. The city itself, a creature of industrial capitalism, couldn't possibly withstand its digitally-networked descendant.

But a city is already a kind of social technology, and Greater New York traces an invigorating cascade that is as fresh as any of our new social networking tools. New York will always be a reliable filter, an organizing schema for work that prizes heterogeneity over a processed theme. PS1 is a very difficult space to keep a tone consistent or even captivating. One can savor the work here only after sifting through its tensions.

Read against itself, the exhibition shows how the most interesting artists are no longer dealing in the dualisms that modernity tried to transcend. Nor can emerging trends in a networked society easily square with a version of history that at times amounts to civic antiquarianism. Today young artists emerge not just from youth, but also from underneath the nostalgia into which Greater New York reinscribes them. In New York, as in the new economy, the periphery is everywhere.

Mike Pepi is a writer living in New York. His work has appeared in frieze, e-flux, Flash Art, Art in America, DIS Magazine, Rhizome, and The New Criterion.

Greater New York, MoMA PS1, New York, until 7 March