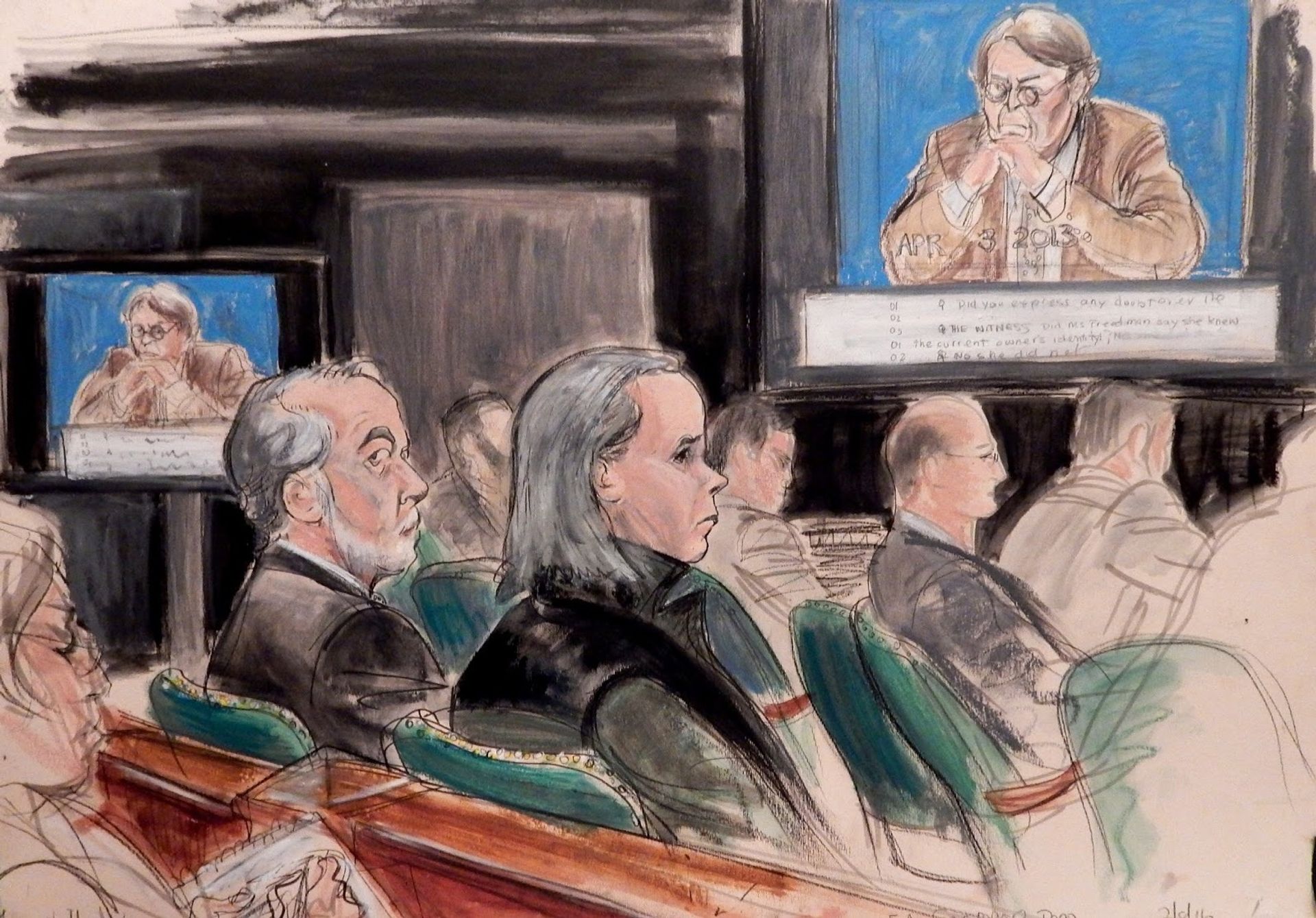

To courtroom observers, the evidence in the Knoedler fakes trial seemed to favour the plaintiffs, Domenico and Eleanore De Sole, who sued the gallery and its former director Ann Freedman for selling them a fake painting purportedly by Mark Rothko for $8.5m. So why did the collectors settle their claim, especially when there were only two days of testimony left? At this point we don’t know, but there were good reasons not to wait for a jury verdict.

“Whenever parties agree to settle, they’re always evaluating the risk that a jury might not come out on their side compared to how much they’re getting paid [in the settlement]”, says the art lawyer Dean Nicyper of Withers Worldwide.

The De Soles’ lawsuit carried significant risk. The collectors’ sought to prove that Knoedler and Freedman committed fraud because they knew or should have known the painting they sold was not authentic.

For one thing, a fraud claim is not easy to win. Convincing a jury involves knowing Freedman’s state of mind at the time of the sales, and that’s “always hard to prove”, Nicyper says.

The jury heard two-and-a-half weeks of evidence that was potentially damaging to the defendants: an accountant testified that selling the fakes kept Knoedler afloat for years; experts took the stand and said they told Freedman they doubted the paintings were authentic; Knoedler researchers testified they couldn’t find a single document identifying the works or confirming a provenance for the collection; Rosales offered the paintings to Knoedler at far below market prices. Faced with these red flags, Martha Parrish, an expert on art-dealer practice, testified a reputable dealer would “run like hell”.

But the jury also heard some evidence favouring the defendants: the National Gallery wrote Freedman that if it published a supplemental Rothko catalogue raisonné, it intended to include the De Soles’ painting; the former Rothko Foundation conservator Dana Cranmer examined some of the Rosales works and, although she testifies that she doesn’t authenticate them, she used words like “genuine” in the condition reports she sent to Freedman. And the case settled before Freedman had an opportunity to testify herself.

In a civil lawsuit, a fraud claim has to be proved not by the usual “preponderance of the evidence” (with 51% favouring the plaintiffs’ side) but by “clear and convincing evidence”. It is up to the jury to decide just how much proof is needed, so plaintiffs have no way of knowing what will put their case over the edge, Nicyper says. “Theoretically, it’s a very high standard”.

Also, the De Soles were seeking $25m—triple their actual damages—which they could have only won if they proved Knoedler and Freedman violated the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (Rico), which requires proving a pattern of fraud as part of an ongoing, organised scheme.

In the end, it all comes down to the jury. “I always get concerned a jury will decide [based on] who they think should win”, instead of following the evidence, Nicyper says.