Spanish Masters from the Hermitage: the World of El Greco, Ribera, Zurbarán, Velázquez, Murillo and Goya at the Hermitage Amsterdam is a show of historic Spanish art organised by the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. The rationale is that there are few Spanish paintings in Holland. Here’s a chance to see, in the words of the director of the St Petersburg Hermitage, Mikhail Piotrovsky, “all the great names known to so many, as well as a large number of works by other superb artists.”

Too many of the paintings, unfortunately, are less superb than fair to middling. Many are 19th- and early 20th-century scenes of national colour, manufactured by minor talents for markets beyond Spain (particularly Paris and Rome) where artists travelled and often ended up residing for long periods. Kitschy representations of sunlit courtyards, haughty ladies, toreros, flamenco dancers, picturesque Arabs and gothic Spanish cathedral interiors by Vicente Palmaroli, Martín Rico, Federico de Madrazo, Hermenegildo Anglada, Ignacio Zuloaga and Marià Fortuny, among others, have curiosity value but little else. It is not subject matter that disappoints, but methods, ideas, vision and originality. Nothing is bad exactly, but the exhibition appears to conceive of art as scenes in a travelogue.

The catalogue is often lightweight where it isn’t dizzy. It’s not analytical but swooning for Natalia Demina, a curator at the St Petersburg Hermitage, to say that Fortuny’s “technique” is that he “scattered the canvas with paints like precious jewels.”

Aesthetic ideas are never approached seriously but referred to distantly in the form of lazy flights, the tone of which is set in Piotrovsky’s forward. Goya: "mysterious and tragic.” A painting by El Greco: “explosive inner tension." And what “emanates” from paintings by Zurbarán and Ribera? Why, “sublime exaltation”!

It’s an interesting achievement to make Goya disappointing, but this show manages it. We’re strongly led to believe on the first page of the catalogue by a brief anonymous announcement beside the list of sponsors and partners (banks, multinational corporations and companies producing petrol, alcohol and TV programmes) that all Goya's major print series are on show. In Piotrovsky’s introduction we read: “This exhibition includes nearly all the famous series of prints by this mysterious and tragic artist, whose work has such resonance today.” In reality, only a few works have been sel ected from three of the major series. There are four prints from The Disasters of War (created 1810-20), 12 from Los Caprichos (published 1799) and eight bullfight scenes (published 1816). Plus there is a couple unconnected to any series.

How could one elaborate on the “resonance” Goya has today? It would be great to hear, considering the obvious social parallels: unending terrorism, arbitrary military invasions and naked exploitation of the poor by the rich. Then there is a subtler issue, the unresolved paradox of Goya’s outward social conformity and the savage social satires that were often the content of his art—but Piotrovsky is silent.

Was Goya really as he appears here, an unchallenging fantasist who was efficient at observing bullfights? To help with the latter subject, a colour film of a bullfight, scaled for a small cinema, is projected in the exhibition. It connects Goya to a Picasso display. This should be fair enough, but the show’s Picasso moment is awfully strained. A few decorated ceramics, an undistinguished early still-life and two Rose Period gouaches (Boy with a Dog from 1905 and Naked Youth from 1906) are rendered absurd by a wall-sized photo showing Picasso posing with a Spanish guitar.

The head of the Hermitage Amsterdam, Cathelijne Broers, also supplies an introduction. (Between her and Piotrovsky, they manage 1,300 words.) Broers says Velázquez is Spain’s equivalent of Rembrandt. He “stands head and shoulders above the rest, the greatest of the great, always beyond imitation. Every line, every colour, every composition is striking in its power, in its inherent rightness.” Again, as with Piotrovsky, one wonders about the responsibility of museum officials to come up with fresh interpretations of cultural achievements.

All the main essays are by curators from the St Petersburg Hermitage. None show any awareness that there is a show on. The articles all could have been written 50 years ago. Ludmila Kagané informs us with stunning repetitiveness that Spanish artists are expressive with light and shade. It’s true, of course, but how about some insights? Instead we get “sharp contrasts of light and shade” for Ribera, “violent contrasts of light and shade” for Gordano, and “sharply contrasting light and shade” for Zurbarán. It is nearly refreshing to read that Francisco Ribalta has “interesting illumination.” A phrase employed for Velázquez’s genre scenes depicting bodegons appears to hold out promise. However a bodegon is a cafe or bar quite likely to be in a cellar, and therefore to describe the quality of Velázquez’s lighting in this context as “cellar-like” cannot be counted as an eruption of genuinely imaginative language.

Beside 60 paintings lurching between fabulous and bilious, there are contextual objects: furniture and weapons, jewellery, New World sculpture, and so on. Here the quality control is firmer than with the fine art. But staging these beautiful things in mock-ups of real rooms so the viewer can imagine he or she is peering into living spaces where real Spanish persons from the 17th century might be about is a bit childish.

The heart of Spanish Masters is a single display in a large space of 35 17th-century paintings. Again the soaring heights have to contend with ill-matched curatorial energies. A wall label explains four paintings each showing semi-naked men in contorted poses. We are told they exemplify Spanish interest in the relationship between suffering and religious piety. While this works for the first three, which depict Catholic saints, it certainly doesn’t for the last one, featuring pagan gods. Another wall label relating to portraits by Velázquez oddly appears to ask that the reader identify a prime minister as “ordinary.” The Royal Court, too, is supposed to be an “ordinary setting.” When this textual surrealism also includes the phrase “strong contrasts of light and shade”, it’s almost insulting.

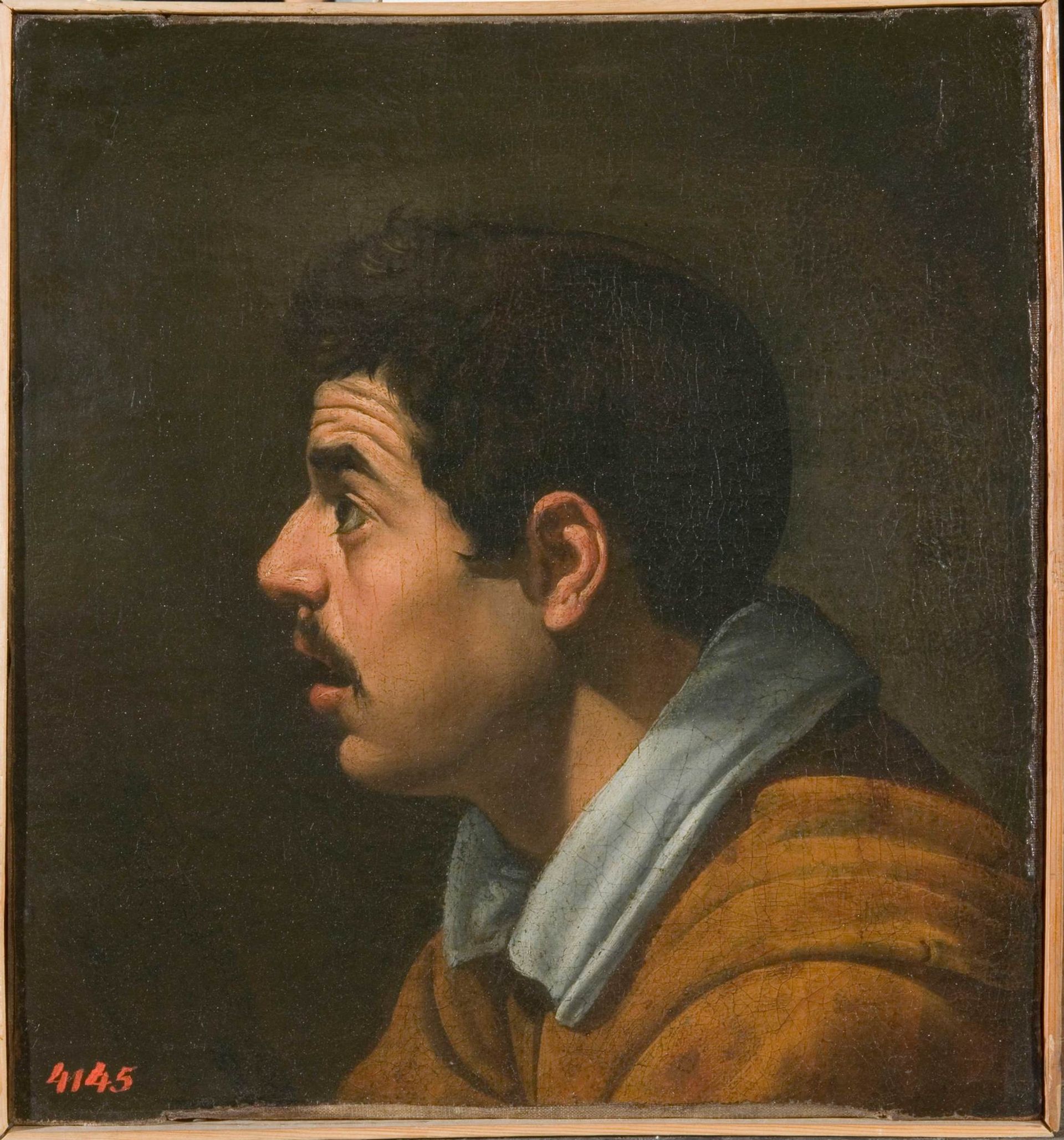

It is a shame, since Velázquez’s treatment of light really is, of course, what makes him important. Together, two small works, Portrait of Count-Duke Olivares (1638) and Man’s Head in Profile (1616-17), powerfully summarise the uniqueness of his approach to realism throughout his career—a loose but controlled handling in the service of a proto-Modernist, virtually autonomous, marvelous dance of highlights.

Powerful works defeat shabby contextualising, but the feeling of being treated contemptuously as a viewer is galling. The feeling of a hollow exercise for the Hermitage as a tourist hotspot is depressing. Perhaps laziness and forgetfulness are infectious. No doubt there is a word for the emptying-out of culture so that its only content is monetary and its only purpose is the fulfillment of a neoliberal agenda. If I could remember that word, I’d use it to describe Spanish Masters.

Matthew Collings is an artist, writer and TV broadcaster.

Spanish Masters from the Hermitage: the World of El Greco, Ribera, Zurbarán, Velázquez, Murillo and Goya, Hermitage Amsterdam, until 29 May