One of the most inventive and unpredictably nimble artists working in Britain today, Mark Wallinger’s art has ranged from meticulous paintings of racehorses to a presentation of the first public statue of Jesus Christ in England since the Reformation. While Wallinger’s early focus was on British traditions and values, from the 1990s onwards his interests have shifted to a wider questioning of power structures and notions of identity that has spanned photographs, videos and installations—as well as a live performance dressed in a bear suit. He can be simultaneously witty and politically incisive: when he represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2001 he hung a Union Jack flag remade in the green, white and orange of the tricolour, the flag of the Republic of Ireland, outside the British pavilion.

For his debut show at Hauser & Wirth in London, Wallinger is living up to his reputation as an artist who never repeats himself, with a multimedia exhibition of mostly new work that includes a dramatic painterly departure.

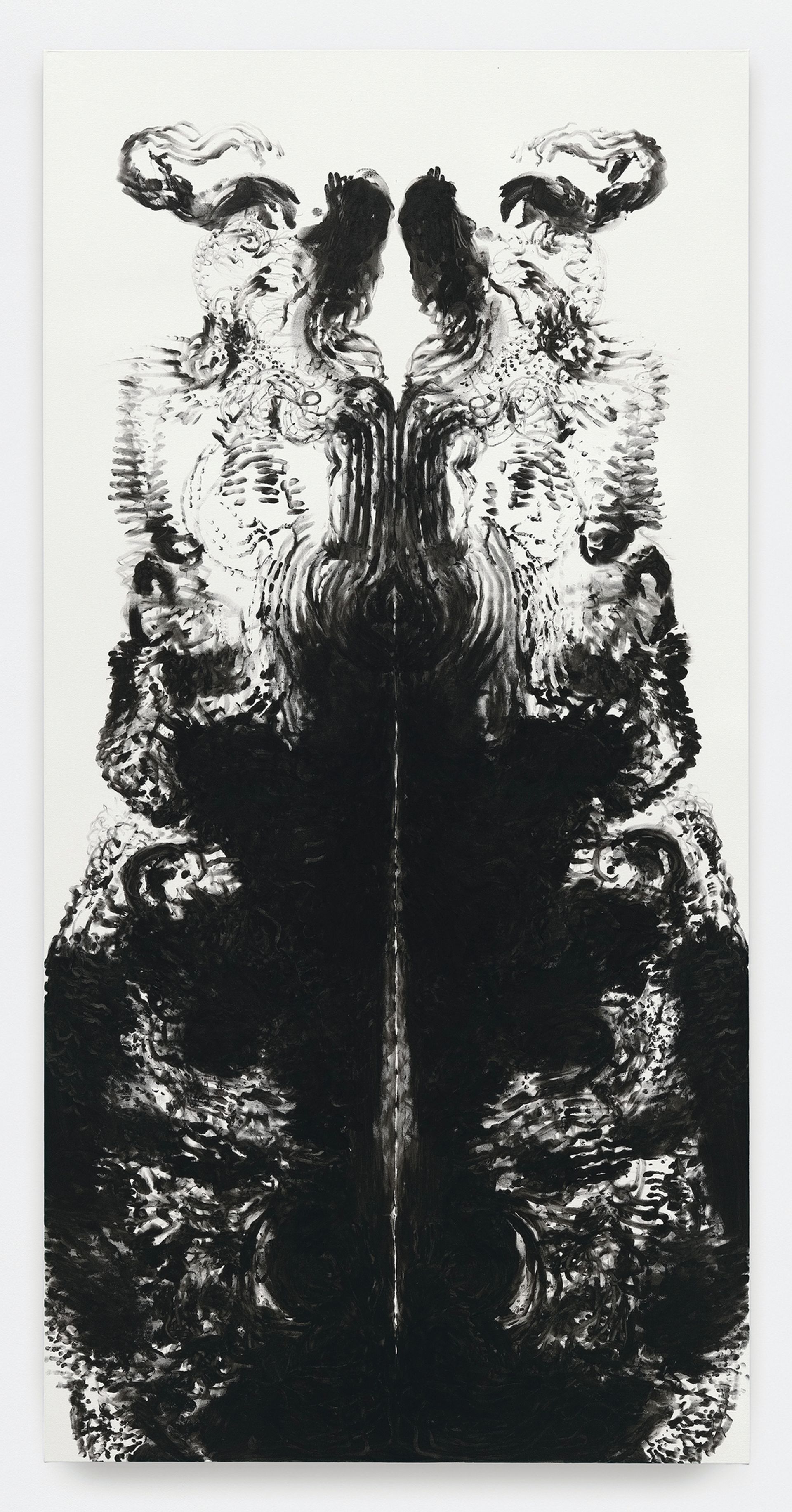

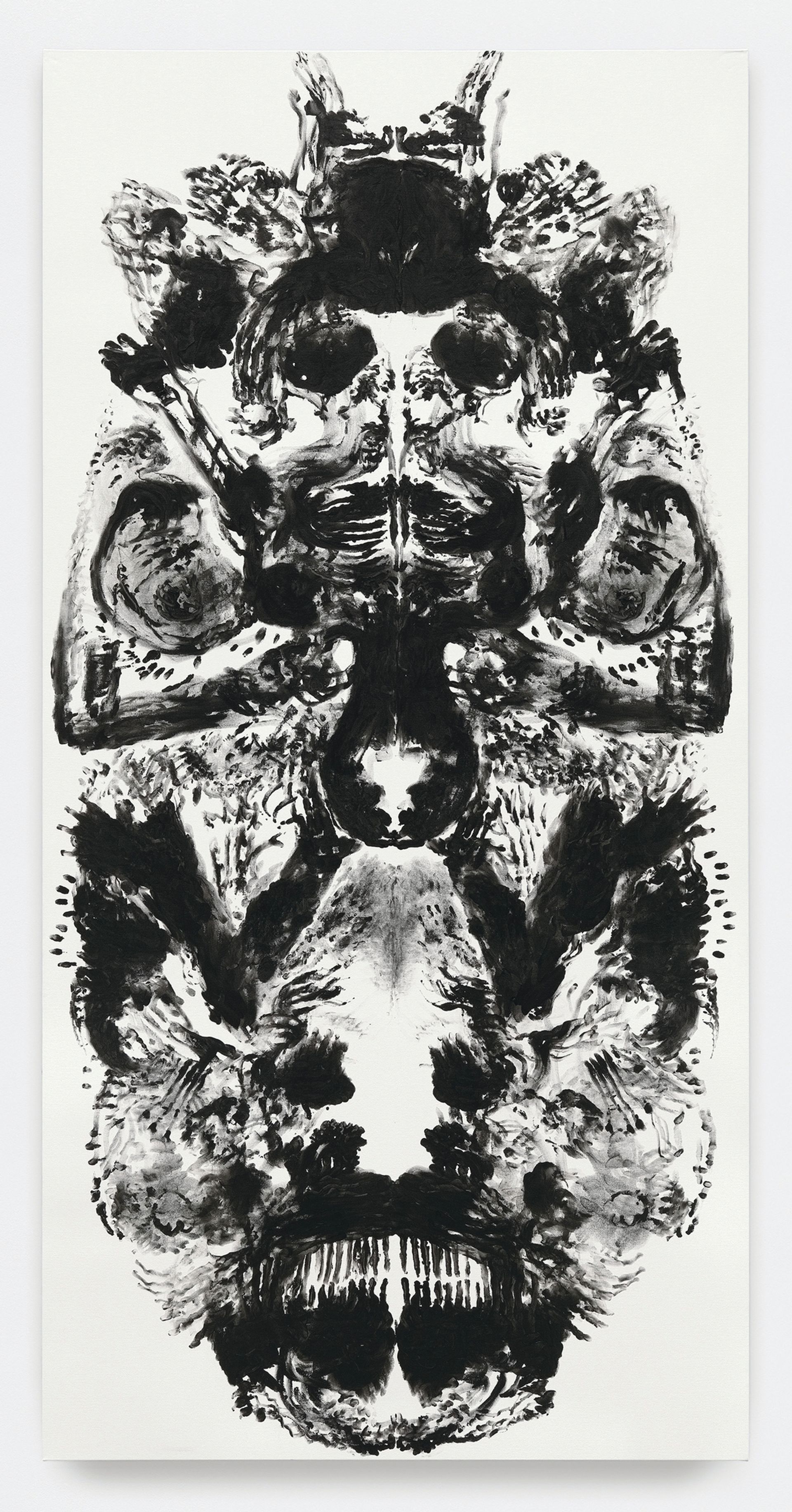

The Art Newspaper: Your new series of monochrome id Paintings are made by applying paint directly to the canvas using your hands, and seem to underpin this show. Are they related to the previous Self Portrait canvases depicting a single black letter “I” in different typefaces?

Mark Wallinger: They grew out of the I paintings in quite a nice, organic way. Last year I moved into this very tall, top-lit new studio and I suppose in a rather Darwinian way I thought, well, let’s order some canvases and take the Self Portrait I paintings up to a sort of Abstract Expressionist scale, and see how that goes.

How did you choose the size of the canvases?

The width is the extent of my arm span and they are double my height. Last summer I made about a dozen that ran the gamut of painterly language and then I started using my fingers to paint, and there was something quite basic about that which I rather liked. But they were still quite wedded to the Is [I paintings] until I made one in which I used both my hands simultaneously and very gesturally and almost blind, because I was right up against the canvas. Then the penny dropped about the bodily proportions and I realised that I could work on that scale and then flip the canvas and be suddenly in dialogue with the other end in a kind of double mirroring. I realised that I could do symmetry quite successfully—maybe all of us can—and I also noticed that something quite curious happens in that, if you give a mark its mirror, almost any gesture gains a kind of authority or purpose. So I made three all in one day and was very excited about what was transpiring, although I didn’t have much purpose or end point in mind. Afterwards I had to go away for a week, but was very excited about getting back to them and they soon developed a life of their own: making them has now become rather addictive.

You’re not going down the Yves Klein full frontal direct contact route?

No, there are no other body parts involved, I can assure you—just every part of my hands.

Although you have always worked in every conceivable medium, making paintings has been an enduring passion from the beginning.

It’s been interesting getting back to something that I haven’t been dealing with for a long time, as more recently I’ve been taking on probably too many public projects that require a lot of process and premeditation and working with other people. So to be in a direct encounter with paint on canvas has been a very liberating feeling and these are the most direct kind of painting that I’ve ever done. Looking back, I’ve always made paintings that to a certain extent have always had a point in mind and have always been in some relation to art history, whereas these suddenly just became the thing itself. So they went from painted Is to “I paint”, which has been quite an odd place to arrive at.

Among the other works in the show are Ego, a photo piece showing your left and right hands in a recreation of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, and Superego, a revolving mirrored sculpture that takes the form of the New Scotland Yard sign. Why have you chosen to couch so much of this show in Freudian terms?

I think it’s kind of admitting that this might be about me now; and those are the terms that have been handed down to us as common knowledge whether we understand them or not, or whether they are a useful or accurate way of analysing the mind. I’ve been in analysis for the last year or so and I suppose I’ve been facing up to myself in ways I haven’t before. I knew the id Paintings were a break with the self-portraiture series, which was a kind of face-off or an accommodation with language and what expression or self-expression could mean. I’ve had a fairly turbulent year, so things have arisen out of that, and out of work again being actually incredibly important to me, because that was a broken relationship for a little while. So they are without irony, really, and it’s a relief to shrug that off.

There’s a more knowing self-examination in the Ego photo piece of your Michelangelo-esque right and left hands.

That’s been on my kitchen wall for a year or so. I like it because it’s knowing about a bunch of things I find interesting. I suppose the notion of the creator or the creative artist and all the rest of it is rather a hubristic thing to begin with, isn’t it? But then I thought, well, it’s a right hand and a left hand so I can do that myself and then it really is like the limits of one’s own existence. I often talk about when you go to the opticians for an eye test and you’re getting down to the bottom line—literally—and you’re asked, “Is this lens better than this one?” And you can’t phone a friend, you are just thrown back on your own senses and there’s really no one but you to consult. In a sense those are the limits to all one’s beliefs about the outside world—and sometimes you do feel alienated from your own body.

On a basic level, you are extending out and up as far as you can with the id Paintings and then reaching inwards with Ego.

Yes, and it’s a bit Vitruvian Man as well, so it’s both Michelangelo and Leonardo. And these [he holds out his hands] are the tools of the trade.

Superego, the rotating, reflective New Scotland Yard Sign has connotations of seeing and being seen at a time when we have never before been so scrutinised but also so anonymous and depersonalised.

You could say that it’s a very knowing piece in terms of its source and in terms of surveillance society and all those tropes that we are familiar with, but actually I think just physically this revolving mirror, which mirrors something above our access to that reflection [the work rotates above eye level], suggests further horizons. I’m hoping that it will give us an almost physical ache about something that’s inaccessible yet which somehow seems to exert a degree of control.

I was thinking of lighthouses: they are multi-mirrored things that send the light out as far as possible. In a sense, this is a reverse of that: it suggests something both repellent and enticing about the kind of scrutiny that’s given justification because people’s security is the first responsibility of government, and all the rest of it.

Two years ago you made the move to Hauser & Wirth after being represented by Anthony Reynolds since the mid 1980s. Is it a very different experience working with such a big, international gallery?

For various reasons I had to move on and Hauser & Wirth have been fantastic to work with. It’s a very close, thorough and supportive working relationship, which has given me absolute freedom to make exactly what I want for this show.

• Mark Wallinger: ID, Hauser & Wirth, London, 26 February-6 May