La Fabbrica del Rinascimento: Frédéric Spitzer mercante d’arte e collezionista nell’Europa delle nuove Nazioni

Paola Cordera

Bononia University Press, 504pp, €60 (hb).

In Italian only

Frédéric Spitzer (1815-90) was a notorious dealer-collector described by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild as “a genius in his own line”. What that line was remains unclear, and this is the first biography to appear—hardly surprising given the lack of archival sources and the need to trace him through clients and fellow dealers. Spitzer is now seen as the co-ordinator of a network of craftsmen in the supply of skilful forgeries of Renaissance decorative art. As Rothschild explained in 1897, “out of one fine old work of art he manufactured two or three”, placing them by “laying great stress on what was genuine in them, and ignoring what was not”. New here is the revelation that Spitzer began his career in London in the 1840s in the ambit of the Rothschilds and that it was at their instigation that he moved to Paris in 1868. Paola Cordera analyses the plan of his apartments and the photographs and catalogues documenting his carefully arranged collection. This useful book ends with a concordance showing the current location of many of his pieces. What emerges is his genius for self-advertisement through his so-called “museum” in Paris as a stage set for a dealer who marketed lifestyle as much as art.

• Dora Thornton is the curator of Renaissance Europe and of the Waddesdon Bequest at the British Museum. She is the author of A Rothschild Renaissance (2015)

Peggy Guggenheim: The Shock

of the Modern (Jewish Lives)

Francine Prose

Yale University Press, 211pp, £16.99 (hb)

This succinct biography of one of the last century’s greatest collectors of 20th-century Western art is an elegantly written account of the difficult and controversial life of Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979) who spent most of her life in Europe. At one point buying a painting a day from the most avant-garde artists, she dedicated herself to helping and supporting artists, and, with her advisers, exercising her adventurous and even original taste. The heart of the collection on display at her palazzo in Venice is outstanding by any measure. She inhabited the most rarified artistic circles but felt an outsider, a poor little rich girl, a secular American Jew, aware of anti-Semitism. Familial tragedies haunted her all her life and contributed to her own destructive psychology, an almost pathological need for love in many forms and a promiscuous life that was more bondage than liberation. Peggy’s terrifyingly numerous liaisons and sexual encounters seem the most prominent part of this narrative. Although the author is sympathetic, even admiring, of her subject, there are not enough convincing insights into the motives and energy that inspired the two galleries she initiated in London and New York, and the collection itself, unprecedented at the time. However, as Prose remarks, Peggy’s “tendency to mythologise herself and the artists she represented helped shape the contemporary art world, to turn artists into celebrities and socialites into art collectors”.

• Marina Vaizey is a freelance lecturer and writer. She was the art critic for the Financial Times and subsequently the Sunday Times. She currently writes for theartsdesk.com

Georgia O’Keeffe

Nancy J. Scott

Reaktion Books, 253pp, £11.99 (pb)

During Georgia O’Keeffe’s lifetime her works were subjected to fashionable theoretical interpretations that frequently made her despair. At the start of her career they were read by critics (and indeed by her lover and later husband Alfred Stieglitz) in a Freudian light as embodiments of a hitherto hidden essence of female sexuality. Towards the end of it, they were celebrated as noteworthy feminist creations, and O’Keeffe herself was represented as an overblown and somewhat vaginal flower in Judy Chicago’s monumental Dinner Party installation. Nancy J. Scott’s thoroughly researched biography steers its way through the theories, putting them firmly in their historical place. It adopts a straightforward, measured approach to O’Keeffe’s life and work, frequently using the artist’s own words drawn from her voluminous correspondence. What emerges is a portrait of an uncompromising figure, who once declared: “I decided I wasn’t going to cater to what anyone else might like—why should I?” Her panoramic landscapes of Texas and New Mexico and close-up views of bones and flowers can be seen as part of the evolution of a distinctively American Modernism, but as James Thrall Soby, one of her more perceptive critics, said: “She created this world; it was not there before; and there is nothing like it anywhere.”

• Caroline Bugler is a writer and editor specialising in art, and was formerly the editor of Art Quarterly

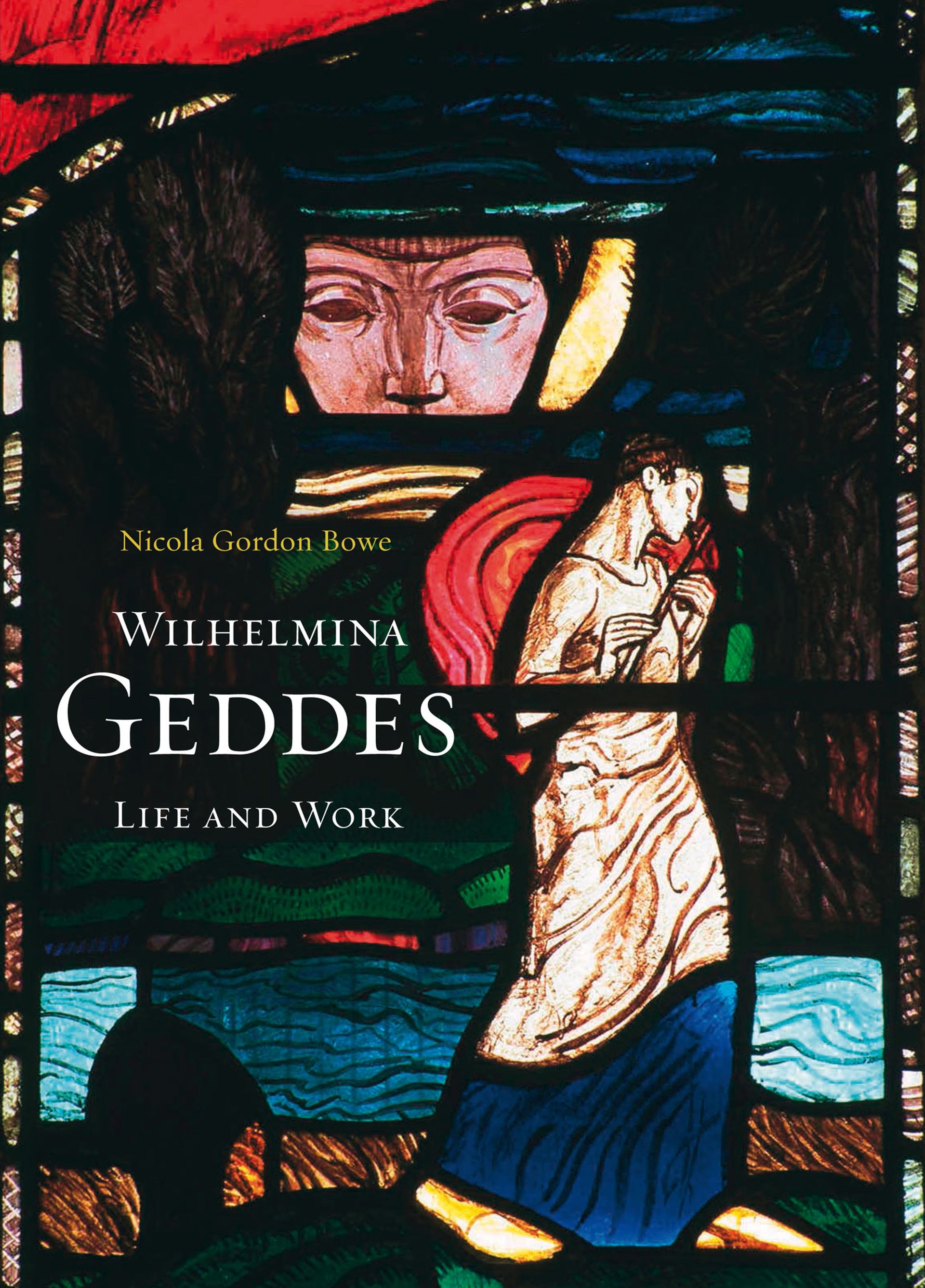

Wilhelmina Geddes: Life and Work

Nicola Gordon Bowe

Four Courts Press, 508pp, £45 (hb)

The name of Wilhelmina Geddes (1887-1955) is hardly well known, but she is described by Peter Cormack (author of the recent masterly Arts & Crafts Stained Glass) as “arguably Ireland’s greatest 20th-century artist”. Brought up in Belfast, in 1911 she moved to Dublin, where she joined An Túr Gloine, the stained glass studio set up by Sarah Purser. In 1925 she moved to London, remaining there until her death, and working in the Lowndes & Drury workshop in Fulham. She suffered constant poor health, both physical and mental, and she was a perfectionist who would repeatedly destroy her work until she was satisfied. None of her windows is in a well-known location. Her most prestigious commissions were for war memorial windows in St Bartholomew’s, Ottawa, Canada, and Ypres Cathedral in Belgium, but she also produced remarkable windows at such remote locations as Wallsend and Laleham in England and Lampeter in Wales. Her figures have an astonishing power, and her sense of colour was superb. Her technique aroused the admiration of her fellow artists. She has achieved less fame than Harry Clarke (on whom Nicola Gordon Bowe has already published a monograph) or Evie Hone, about whom she could be wonderfully catty (“her modernity is incapacity to draw and the rest cribbed from me”). This copiously illustrated book is a worthy tribute to a great artist.

• Peter Howell taught for 35 years in the department of classics, Bedford and Royal Holloway Colleges. He is currently writing a book on the triumphal arch, from Roman times to the present