The Royal Academy of Art's exhibition Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse (30 January-20 April), is clearly aimed at big ticket sales. There are no upsetting revelations in the London show to alarm the scholars—the catalogue is rather like an album—and it will come as no surprise that Claude Monet is the star, with 35 of his paintings included. He is present at the start, in the middle, and at the end, with the Agapanthus Triptych (1916-19), painted during his last years at Giverny.

This set of water-lilies, destined for Rodin’s house in Paris, was sold separately in New York in the late 1950s and reunited for the exhibition when it started at the Cleveland Museum Of Art in Ohio. Monet was a passionate gardener, always interested in the latest trends, and who was devastated when his garden was flooded by the Seine in Vétheuil in the 1880s. An early environmentalist, he lobbied hard to prevent a polluting factory coming to Giverny. Police and local farmers were a bit wary of the alien plants the eccentric Parisian artist was introducing in his park.

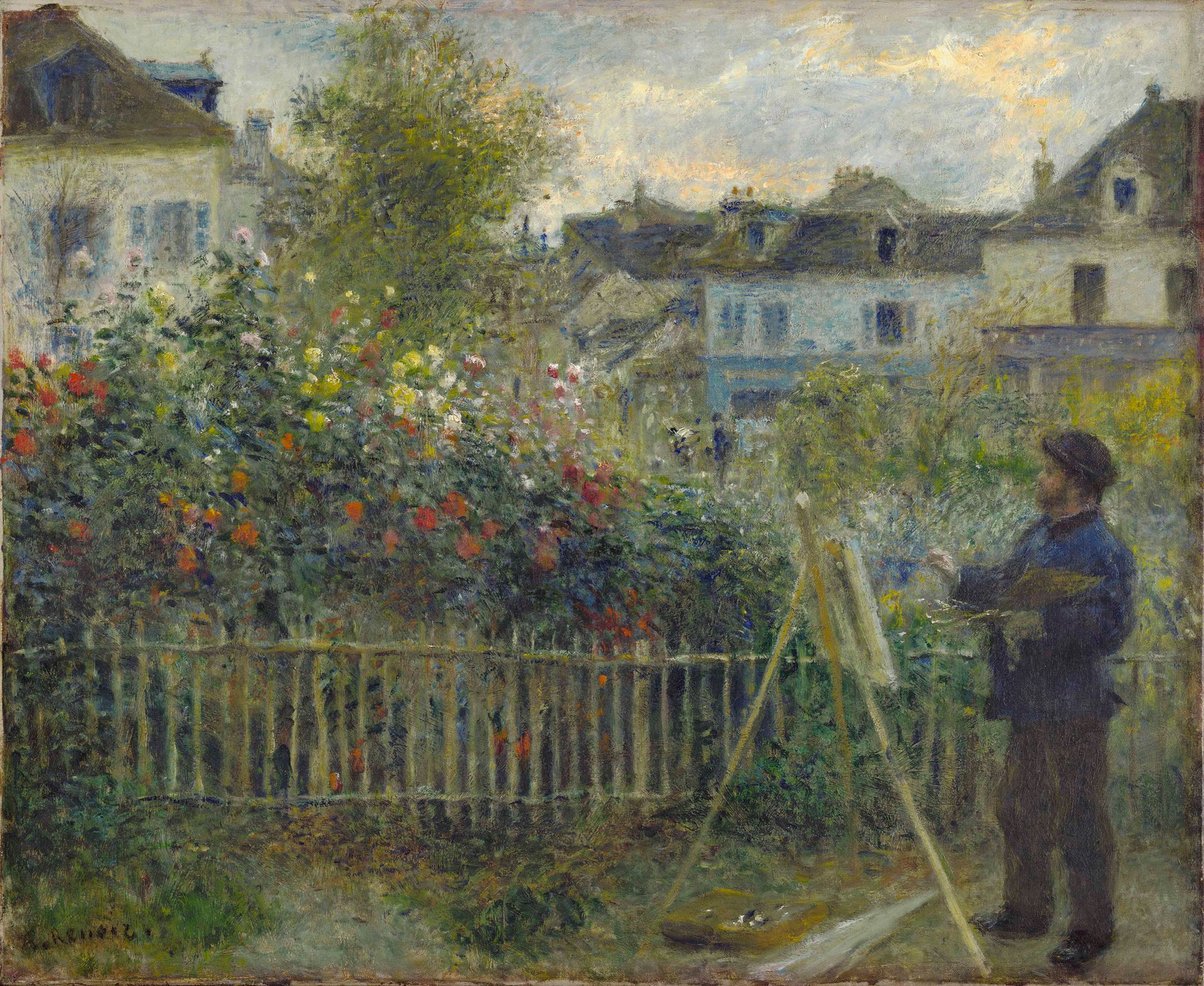

The landscapes on view were created in the wake of the “horticultural revolution”, fuelled by the naturalisation of exotic flowers and technological progress in hybridisation. Artists like Monet or Renoir were influenced by William Robinson’s writings, advocating a (semi) “wild garden”. Beyond the aesthetics, there lays a political and moral message, close to John Ruskin’s ideas: gardening was the new conquest of the rising middle class.

The show includes an astounding panorama by Pierre Bonnard, Resting in the Garden (1914), a vibrant Young Woman Among Flowers (1879) by Edouard Manet and a pair of panels by Edouard Vuillard depicting friends and family in a garden, where Bonnard can be seen on the side playing with a cat. These last two, from a private collection, were not in the Cleveland show.

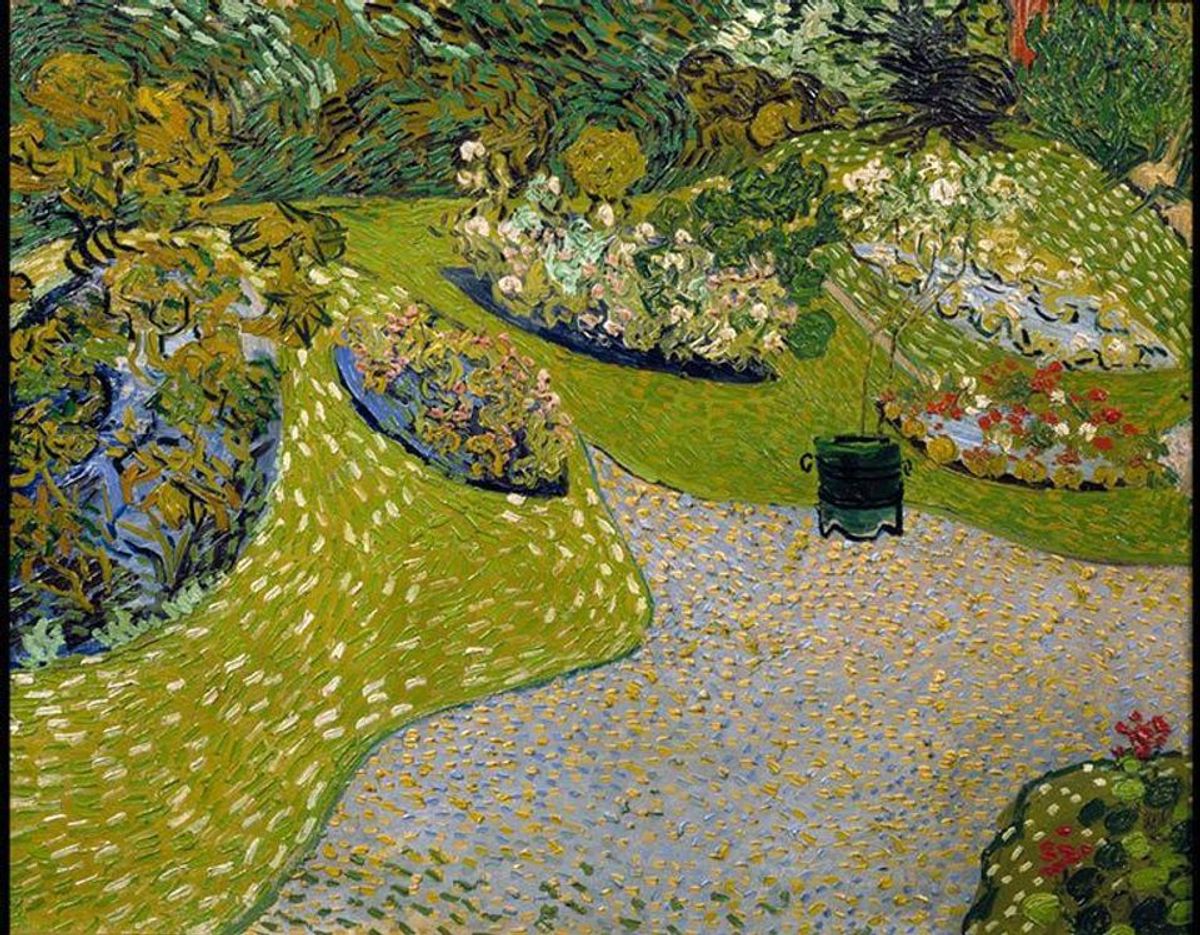

Topics like the tropical garden or the dream of an earthly paradise are not dealt with. Some important artists like Gauguin or even Matisse are hardly present, and there is only one work by Van Gogh—but not just any work by Van Gogh. Garden at Auvers (1890) was praised at the opening of the show by the Cleveland curator William Robinson as “the masterwork of his last days, leaning on abstraction”. But some uncommon characteristics—no sky is visible in this view from above of Daubigny’s garden—were used to trash the work as a fake 20 years ago.

Despite the work’s impeccable credentials (it had come from Theo Van Gogh and had been authenticated by Walter Feilchenfeldt, Ronald Pickvance and Sjraar van Heugten from the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), the claims spread like wildfire in the international media. In 1996, when the family of the late banker Jean-Marc Vernes put it up for auction—at a give-away price—no one wanted it. Its reputation was such that the Impressionist dealer Daniel Wildenstein said, “even if it is genuine, it has become unsellable”.

Soon, other well-established paintings like The Iris, Portrait of Dr Gachet or The Church at Auvers were also denounced as forgeries. It was claimed more than 100 works by Van Gogh in museums around the world were fake. The whole story collapsed in 1999, when the French national museums’ laboratory examined the work with others from Orsay. All passed a series of tests.

Nonetheless, Garden at Auvers has seldom been shown since, so this exhibition can be seen a rehabilitation of sorts of an avant-garde work. In the Royal Academy, the painting brightens the wall as an introduction to other landscapes made decades after the artist shot himself, just a few days after stowing the linen canvas under his bed.