The following excerpt is adapted from Kelly Grovier's new book, Art Since 1989, out now from Thames and Hudson.

In March 2010, a team of Spanish surgeons performed the first full transplant of a human face. A breakthrough in medical science, the procedure was nevertheless profoundly dislocating, not only for the patient who courageously underwent it following a tragic shooting accident, but also for the age in which it occurred. For the first time in human history, features that had once defined the appearance of one individual were now integral to the countenance of another. Oscar Wilde’s famous assertion, "a man’s face is his autobiography", suddenly required reformulation. A visage could no longer be looked upon to record the traumas and triumphs of a single life but was a register of composite existences. From now on, the essence of identity would be as unfixed physically as it had always been philosophically.

The years since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 have seen as great an upheaval in our comprehension of the human face as any age in history. Astonishing medical and technological innovations—from facial-recognition software to full-face transplants—have forced us to focus on the connection between countenance and individual identity. The challenge for contemporary portraitists has been to keep pace with such ingenuity, to reinvent the face for a new age.

For some, such as the Czech miniaturist Jindrich Ulrich and the German Surrealist painter Neo Rauch, the way forward has been the way back, scavenging from scrap heaps of history ambiguous ingredients from which a novel countenance can be assembled. Virtually unknown beyond Prague before the Velvet Revolution in 1989 that brought an end to communist control of his native country, Ulrich gained a provincial reputation fame as "the last Medieval miniaturist" for his countless pocket-sized portraits that managed to merge meticulous Old Master technique with innovative and often playful contemporary vision. Rarely larger than a few inches in height, Ulrich’s works conjure the Bohemian past of Rudolf II’s eclectic court of astronomers and alchemists, necromancers and ne’er-do-wells by dividing a portrait’s profile into a cabinet of tiny compartments into which still smaller constituent curiosities relating to Prague’s occultist past were carefully tucked away. To peer into the cubbyholes of an Ulrich miniature is to witness the secret safe-keeping from political threat of a people’s at once sophisticated and superstitious past, in anticipation of later retrieval and rehabilitation.

A very different kind of artistic resuscitation is evoked by Rauch. Associated with the post-reunification movement known as the New Leipzig School, Rauch’s work involves the merger of past artistic references with contemporary concerns. The figures portrayed by Rauch are often clad in antiquated dress, recalling iconic European revolutionary struggles from the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 20th. The literal dramas in which these subjects are involved are often indeterminate from the clues provided, aligning Rauch’s imagination in the estimation of many commentators to Surrealism. But where pioneering works that define that earlier movement, such as Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931), were invigorated by emergent ideas concerning psychoanalysis and human consciousness, Rauch’s work is illustrative of an age preoccupied by the brutal dismemberments of history and the recombination of cultural shapes.

Such awkward reconciliations of the historical with the contemporary likewise enliven the work of the New York-based African-American portraitist Kehinde Wiley. A restaging of Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps at Grand-Saint-Bernard (1801–05) is characteristic of Wiley’s technique of reimagining works by canonical artists of the Western tradition set against a jarring intricacy of interior textile design, which serves to amplify the cultural clashes the artist is choreographing. The result, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps (2005), is a vibrant recalibration of overly familiar artistic situations whose compositions have become fatigued under the weight of too much staring.

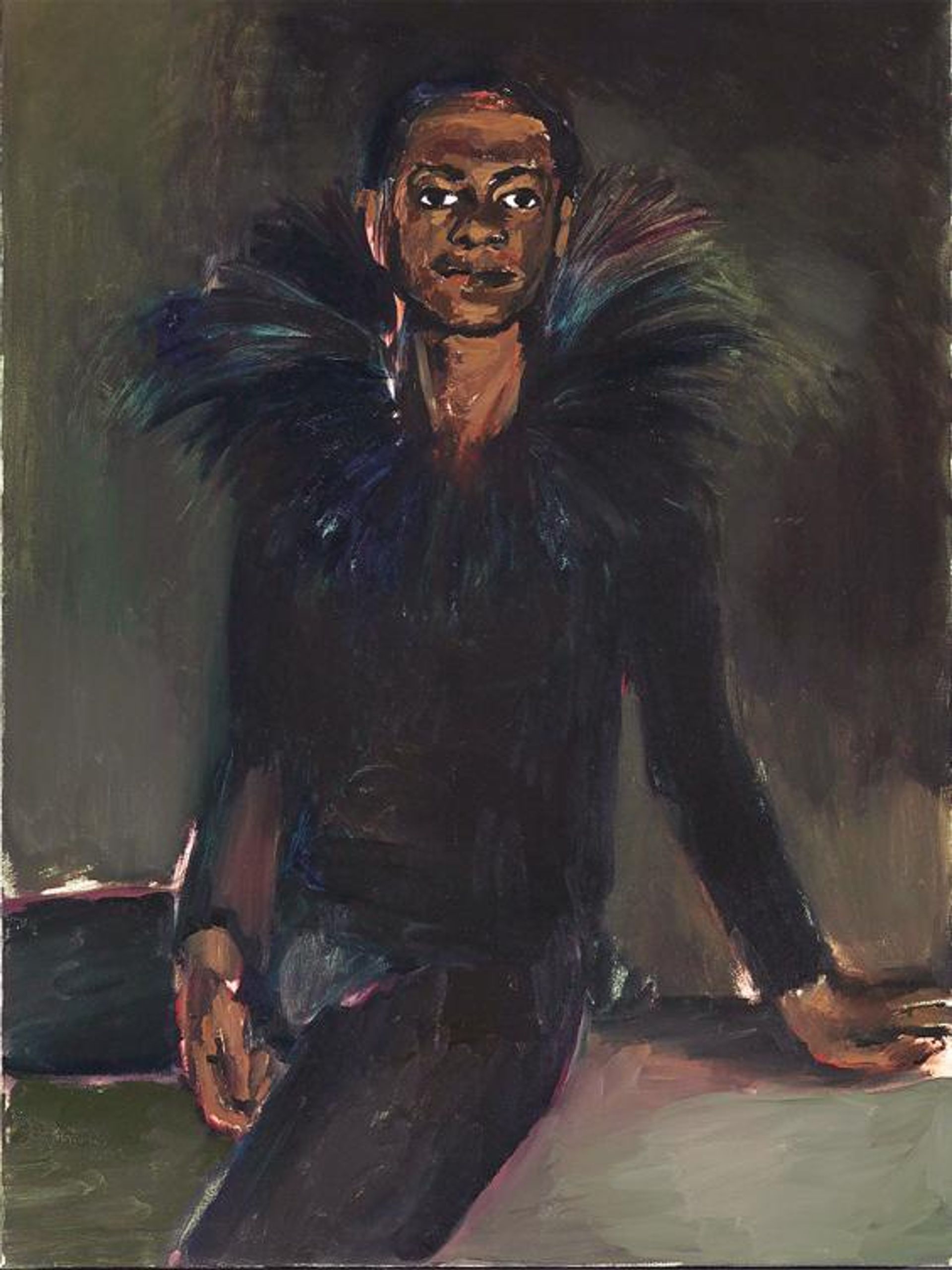

For the London-born painter Lynette Yiadom Boyake, the ambition to shine new light on an old tradition of Western portraiture has resulted ironically in the strict rationing of light not only from her depictions but from the very spaces in which they are exhibited. Boyake’s portraits, almost exclusively of black subjects rendered in dark hues often against dim backgrounds, strive to resist any conspicuous allusion to earlier works in the tradition or indeed to any actual person or place. Constructs from her imagination, rather than representations of real sitters, the artist’s work is characterized by a timelessness of natural setting uncluttered by objects that can tether the vision to any particular era or location. The visionary otherworldliness of Boyake’s work has occasionally been accentuated by the bold curatorial decision to display the artist’s portraits in galleries that enforce near darkness on the viewers, the canvases themselves made visible only by the careful positioning of spotlights.

Where some have sought to reconfigure the face from intellectual references to history, other artists have striven instead to marshal more elemental material components to reconstitute the human countenance, broadening our understanding of what comprises identity both physically as well as psychologically. In the case of Chuck Close, an American portraitist who, in 1988, suffered a paralyzing spinal artery collapse at the age of 48, leaving him unable to hold a paintbrush in his hand, the aesthetic reconstitution of identity mirrored an arduous physical rehabilitation. No longer able to work in the hyperrealist style on which his reputation had been building since the 1960s, Close was forced to reinvent himself and his art. A period of convalescence and physiotherapy returned sufficient function to the artist’s arms (though he remains reliant on a wheelchair) to allow him to strap brushes to his wrist and to begin experimenting with a distinctive technique that breaks a portrait down into small cells that he fills with squirts of paint. The result is a poignant pointillism of amorphous elements that cohere from a distance into a recognizable face, as though the portrait were endlessly decomposing and recomposing into constituent atoms before the viewer’s eyes.

For the British sculptor Marc Quinn, the assemblage of self is achieved with gruesome literalness. Where Close conjures form from a matrix of measured formlessness, Quinn, in an ongoing series of sculptures entitled Self (begun in 1991), reconstructs from siphoned pints of his own blood perishable moulds of his head. Repeating the process every five years, the artist freezes friable jellies of platelets and cells, preserving a fragile record of a single individual’s existence in the world. Quinn has compared his technique to the serial self-portraiture of Rembrandt and Vincent van Gogh. For both Close and Quinn, representing the human face is an obsessive enterprise that allows the artist an opportunity to explore the feeble equilibrium that is being in the world. Where Rauch invites the viewer to contemplate the disaggregation of self into historical signs and cultural allusions, Close and Quinn shake individuality through an imaginary sieve, granulating identity into material components.

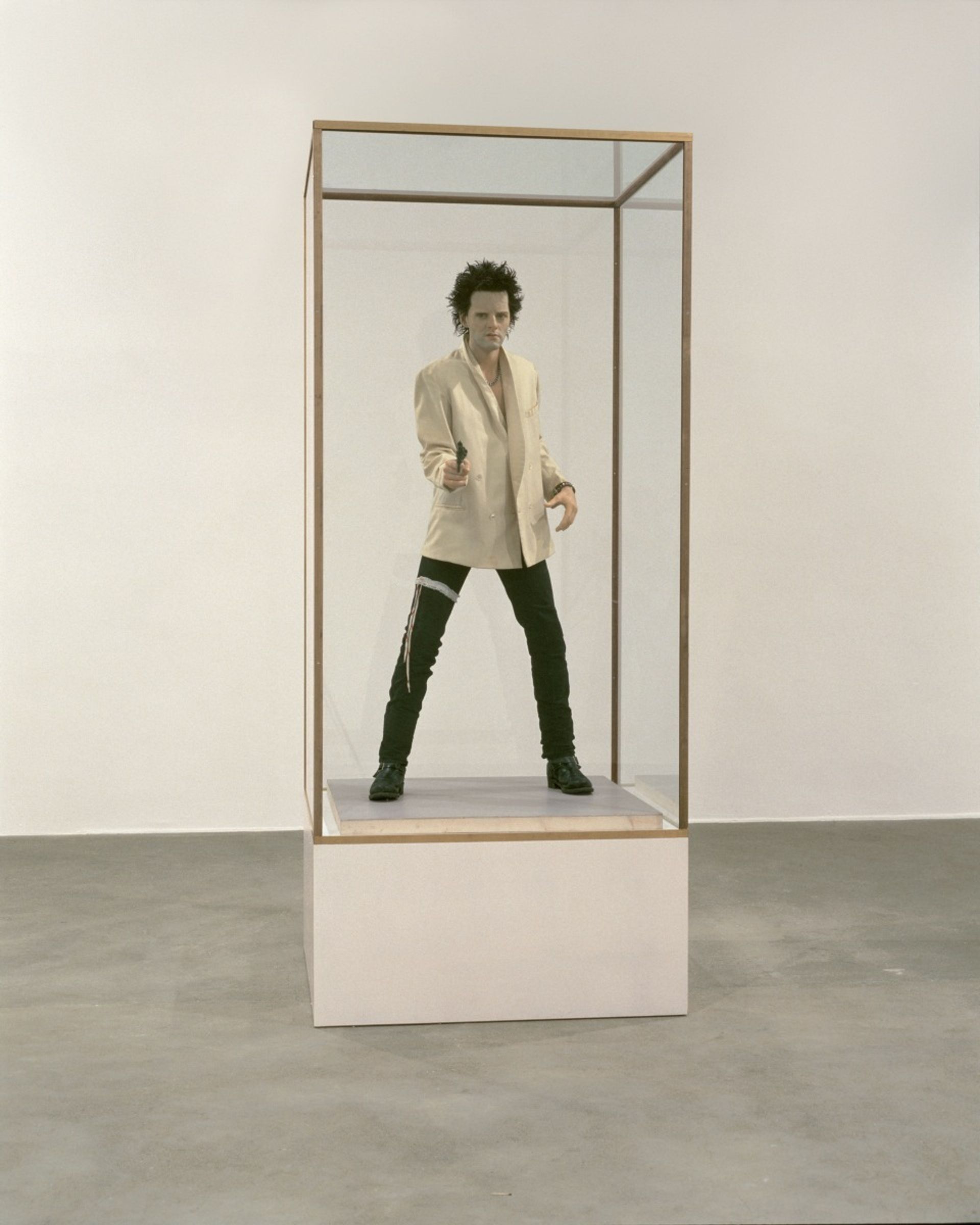

The British sculptor Gavin Turk has also attracted attention for his distinctive experiments with self-portraiture, and in particular for his respective ability to inflect his works with sharp social irony. Turk’s waxwork sculpture, Pop (1993), a life-size self-portrait of the artist assuming the guise of the notorious punk-rock guitarist, and member of the band The Sex Pistols, Sid Vicious, who in turn is impersonating Andy Warhol’s famous silkscreen depiction of Elvis Presley in the stance of an American Hollywood cowboy. Pop is an undisentanglable wad of unapologetically contrived personality, whose manufactured egos are knotted so tightly it is impossible to tell for certain where one identity begins and another ends. By calling acerbic attention to the artificial roles we play in society, Turk invites us to consider to what extent even our truest selves are really us at all.

If the intention behind the techniques of contemporary painters such as Close, Quinn, and Turk has been to isolate the essence of a subject by breaking the sitter’s expression down to irreducible elements (whether physical or, in Turk’s case, cultural), it has been the intuition of notable contemporaries working in the field of photographic portraiture to fashion instead artificial masks in order, paradoxically, to expose the psychological and spiritual tensions of the individual underneath. A significant leitmotif of contemporary portraiture, which has characterized the work of artists such as the American photographers Nan Goldin and Cindy Sherman, has been the resuscitation of human masking, a creative preoccupation whose ancient origins pre-date Neolithic times.

Goldin is best known for her photographic chronicling of drag queens and gay culture, a milieu with which her work has been preoccupied since the late 1960s, when the artist was in her teens. For Goldin, the most intense images are those that capture subjects in moments of unguarded guardedness, where an individual is permitted to preserve the careful choreography of his or her transgendered disguise in an otherwise unposed and informal situation. Characteristic of the emotional texture of Goldin’s work are her 1991 dressing-room portraits of the celebrated hairstylist Jimmy Paul (drag name "Paulette"), preparing for a Gay Pride parade. The friction between the fiction of an invented persona on the one hand and the uninhibited gestures and expressions that such contrivance ironically enables on the other is fundamental to the power of Goldin’s work.

Where Goldin’s photographs document the moving, unrehearsed pageantry of spaces that sprawl on the border between private and public identities—the dim anterooms and mirrored vanities where individuality is awkwardly forged—Sherman’s work is unselfconsciously staged and disconcertingly artificial. Having attracted attention in the 1980s with a series of photographic self-portraits in which the artist adopted the guise of Hollywood starlets from the 1950s and 1960s, Sherman turned her attention to the reinvention of old master portraiture. Her series History Portraits (1988–90) irreverently subverts familiar art historical scenes and cumulatively implies that even the most contemporary of countenances is a carefully rehearsed masquerade of half-remembered attitudes and inherited postures.

An elegant inversion of the conventional gallery gaze also occurs in one of the most talked about works of the era: the Serbian performance artist Marina Abramovic’s inimitable reinvention of the tradition of self-portraiture, The Artist is Present, which she undertook in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, over the course of 736.5 hours in the spring of 2010. For that almost inconceivable length of time Abramovic, who came to prominence in the 1980s with a series of punishing displays of personal stamina, sat motionless at a table in the museum and invited visitors to sit opposite her and to peer into her eyes for as long as they could bear. Each participant witnessed something that none before or after could: a human being at a perishable moment in her life, sharing the silence of an unrepeatable encounter. Visitors to galleries are of course accustomed to looking deep into the unflinching eyes of a drawn, painted or sculpted fiction that they convince themselves embodies a semblance of the humanity that created it. The Artist is Present melted such ritual into reality while poignantly preserving the façade of a portrait’s quiet impassivity.

The heavy cloaking of character is likewise at the heart of one of the most arresting photographic projects of the age: Shirin Neshat’s series of black and white portraits from 1994, entitled Women of Allah. After studying in New York during the formative years of her education, a period that coincided with revolution and the rise to power in Iran of the Allatollah Khomeni, Neshat returned to her native country to find herself lost in a society whose new laws and obligatory customs she scarcely recognized. The most striking dimension of the Women of Allah series is the webbing of the artist’s own face with Persian calligraphy: extracts the artist transcribed over the developed photographs, but which have the appearance of a worn veil of words, a second skin of lyrical assertion whose meaning Neshat knew would be lost on most Western viewers of her work. As in the portraiture of Goldin and Sherman, the superimposed masks in Neshat’s photographs emphasize the complex tissue of tensions—political, sexual, religious—from which contemporary identity is woven.

Kelly Grovier is a poet and art critic.

Excerpted from Art Since 1989, by Kelly Grovier. © 2015 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London. Reprinted by permission of Thames & Hudson Inc.