Art and artist documentaries have been part of the Sundance film festival programme for more than a decade. At this year’s event, which opened in snowy Park City, Utah, last week and runs until 31 January, visitors can see films on Robert Mapplethorpe, Cai Guo-Qiang and an entire section dedicated to virtual reality.

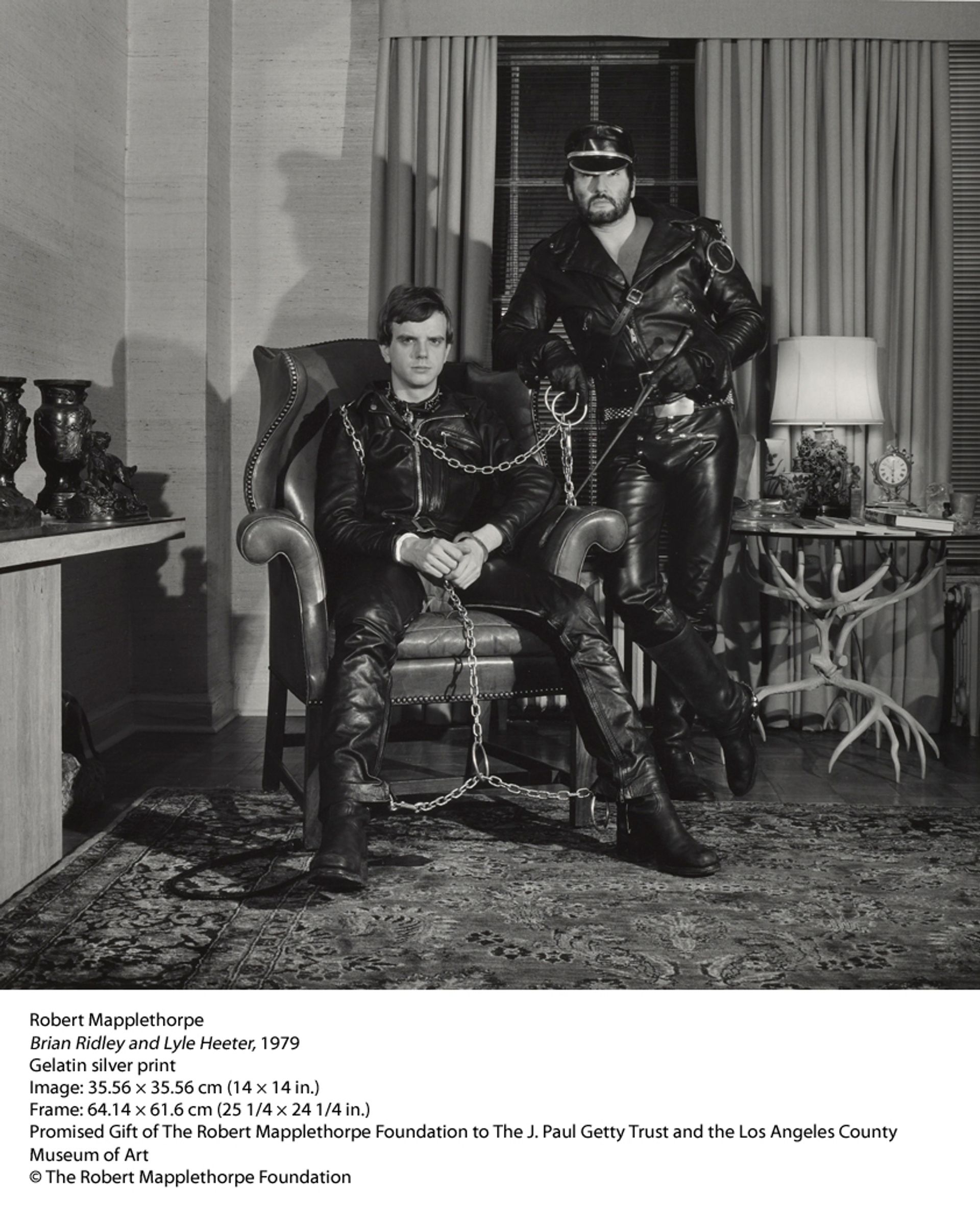

The documentary Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato, which premiered at Sundance, will air on HBO in March to coincide with the opening of two massive shows of the photographer’s work at the Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Since the film tracks the organisation of the exhibitions, there is much opening of flat files and formalist curatorial discussions of the positioning of a bullwhip in a very private place.

The film also leads the audience through Mapplethorpe’s life (1946-89), from a Catholic boyhood on Long Island in New York—we even hear from his priest—to art school in Brooklyn, his early days with Patti Smith, and the homoerotic pictures that made his notoriety.

“Look at the pictures!” is what Senator Jesse Helms shouts in an archival clip as the film opens, reminding the audience that Mapplethorpe became the symbol of transgressive art at the time, and the poster boy for a campaign to block the US government from funding culture.

Those culture wars led to the cancellation of the 1989 exhibition, The Perfect Moment, at the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington, DC, and to the prosecution of Dennis Barrie, the director of Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center on obscenity charges. (He was acquitted.) In response, the Mapplethorpe Foundation and the artist’s estate stopped supporting exhibitions of his work in the US, focusing on building a following and a market for the photographer’s less provocative still-lifes and portraits. The gambit worked and values soared.

The film and the exhibitions are now evidence that Mapplethorpe, if not a classic, has his place in history. At a post-premiere party in Park City, local men in skimpy leather suits walked each other on leashes and played sadomasochistic games in an art gallery in front of enlarged Mapplethorpe prints on the walls. Demonised 25 years ago, Mapplethorpe now even has admirers in largely conservative Utah.

Meanwhile, the Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang is the subject of the film portrait Sky Ladder: the Art of Cai Guo-Qiang, directed by Kevin Macdonald, who made The Last King of Scotland in 2006, and produced by Wendi Murdoch, Fisher Stevens and Hugo Shong.

The bio-doc is named for a ladder-shaped firework piece Cai realised last summer that extended 500 meters into the air near Quanzhou, China. Once ignited from the ground, the delicate strand climbed burning into the sky for all of two minutes and 20 seconds. The project was a reflection on the fleeting nature of human creation in a land of ancient monuments.

Macdonald also tracks Cai’s other projects over the years, including the elaborate opening ceremony for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics (for which he was criticised for using digital recordings instead of live fireworks), and his use of natural dyes in explosives that gives those displays the lingering composure of still-life paintings.

We learn that fire has a history in Cai’s family. The artist’s father managed a government bookstore and collected books himself, bringing him into disfavour during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, when “bourgeois luxury” was a crime. Cai recalls in the film that the books burned for three days.

And if Sky Ladder is the festival’s salute to immateriality, Sundance’s New Frontiers section, devoted to virtual reality, is its gaze toward the future of moving pictures.

Tech trumps content here, although many of the VR films observe nature at risk. Lynette Walworth of Australia presented Collisions, a look at landscapes affected by British nuclear weapons tests in the 1950s on lands inhabited by aboriginal people. The panorama in all directions surveys vast stretches that were deemed worth sacrificing.

Condition One of San Francisco redefines gore in three dimensions with a documentary of a visit to a Mexican slaughterhouse, which is as immersive and tactile as can be imagined. The VR filmmakers, founded by the former war photographer Danfung Dennis, have also created virtual contact with bison and jaguar. If these works aren’t necessarily art—a matter of debate—they could be ideal for science museums.