The Day of Anger on 25 January 2011 signalled the start of the Egyptian Revolution. After the Tunisian uprisings, protests in the Egyptian capital, Cairo, and across the country paved the way for the so-called Arab Spring, which swept across the region. Today, five years on, many who witnessed or took part in the protests consider it a failed revolution. Although the uprising, in which more than two million people took to the streets across Egypt, ended in the overthrow of then-president Hosni Mubarak, the country has experienced a turbulent transition since. Culturally, the gathering of young protesters in public spaces in 2011 led to an artistic outpouring that included street art, performance, photography and film. Despite the censorship that is increasingly seen within the country, this collaborative creativity has led to a number of art projects that are keeping the revolutionary spirit of the uprising alive.

Street art was one of the most widespread, and unexpected, forms of artistic expression that came out of the 2011 uprisings. Covering walls with images and slogans about freedom and social justice was part of the protesters’ strategy to reclaim the streets from state powers. Women on Walls (WOW) took this budding art form and used it to highlight one of the problems that became increasingly apparent during the revolution—women’s rights. Launched in 2013, WOW now has more than 60 affiliated street artists (both men and women). The initiative has hosted graffiti workshops and held street art festivals across the world to help empower women in the Middle East.

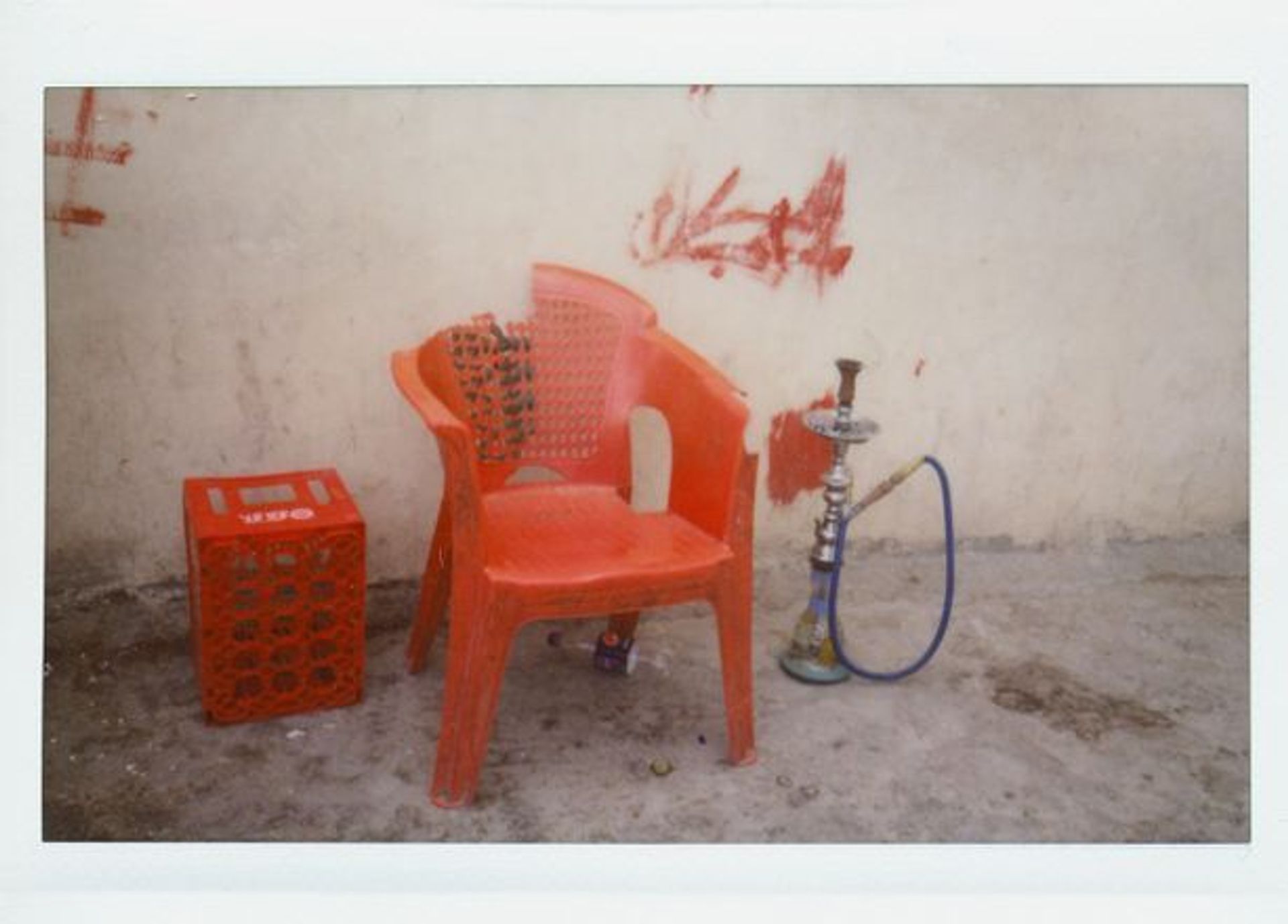

Public space was reclaimed during the 2011 Egyptian uprisings, but it also became a home for protesters who camped out in places such as Tahrir Square. Since then, many artists have seen the streets through new eyes. 1001 Chairs of Cairo paints a picture of the capital through the humble street chair. These disregarded pieces of furniture, scattered on pavements like solitary salons, are inescapable in Cairo. They come in many shapes, sizes and varying degrees of dilapidation, but the project’s creators, Manar Moursi and David Puig, say that they offer an “intimate portrayal” of Cairo, its people and its urban dynamics. So far, the project has been turned into a book and an interactive Google map so that people can discover each of the 1001 chairs for themselves.

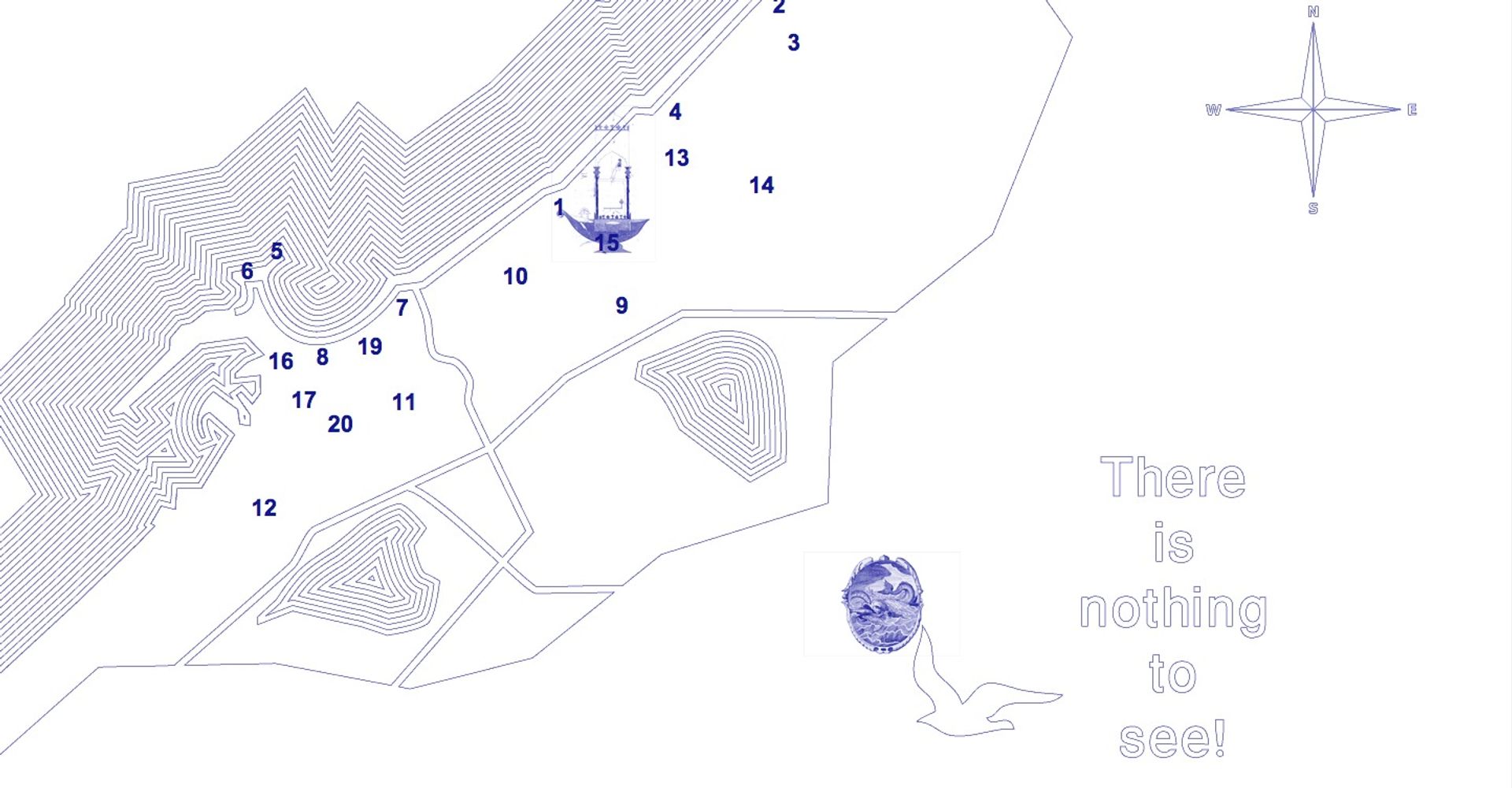

As the epicentre of the 2011 uprisings, Cairo often overshadows other Egyptian cities that played an important part in the protests. Alexandria is one such city, which the curators Berit Schuck and Julia Tieke want to emphasise through “sonic” mapping and radio broadcasts. The German creators developed the project with the help of residents of Alexandria. Through 20 short audio pieces in Arabic and English, the project captures people’s memories and stories of “recent political events, historical structures and forgotten encounters” and brings life to the parts of the city that the eye may not see.

As the arts blossomed during and after the 2011 uprisings, the lack of infrastructure and institutional support (particularly for contemporary art) became ever more apparent. Medrar.TV, a web-based channel that produces videos about contemporary art exhibitions and events in Egypt and the Middle East, was launched in early 2012 with the aim of bridging the gap between artists and the public. The channel’s coverage includes exhibitions, multi-disciplinary festivals, performances, concerts, workshops, artists’ studio visits and interviews. The videos are produced in Arabic and English.

Social media is believed to have been an integral part of the protests in Egypt. Twitter and Facebook were used to bring people to the streets, arrange meeting points and spread revolutionary slogans. The DI-EGY Fest 0.1, a digital arts festival, took place in Cairo in 2013, based on the idea that technology can do anything—even start a revolution. Bringing together Egyptian and international artists who incorporate new technologies into their works, the festival featured exhibitions, screenings, conferences and workshops. It was considered groundbreaking for bringing together public and private sponsorship. But three years on, Cairo is still waiting for a DI-EGY Fest 0.2.