This review was originally published in 2013, when David Bowie Is opened at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. The exhibition is now at the Groninger Museum, Netherlands, until 13 March.

British Rock burst upon the world with a spectacular ferocity comparable to that of the Ballets Russes 50 years earlier. The Russian ballet created complex intellectual works of collaborative genius—rock was always more individualistic and star-driven—but both were powerful performance arts that revolutionised taste, and rock music had much the greater impact on social and political change. (There is a big exhibition that ought to be mounted somewhere: British Rock 1963-93—from the Beatles to Dance. May I curate it please?) Meanwhile, two spaces in the Victoria & Albert Museum, the first white, the second black, have been devoted to David Bowie, one of Britain’s most gifted songwriters and performers.

Despite a cultivation of rootlessness from the outset, Bowie’s is a very British, even very London “art”. His music grew out of the ambitious sound-world of the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper and Pink Floyd’s first album, both of 1967, and his performance has the fantastic cross-over qualities of music-hall and pantomime.

But the growth of entertainment technology allowed him to take it all in unexpected directions, fuelled by the transgressive Zeitgeist of the 1960s.

Trained in alternative theatre and clubs, Bowie eventually performed to stadium level in many countries, and this training has helped him project successfully through virtual media in his later career.

Subsequently, the massive rock show, once so overwhelming (some examples are featured in this exhibition), has been rendered quaint by Danny Boyle’s 2012 Olympic electro-baroque, in which the stadium itself was a gigantic light-machine (which also reminds us that the global celebrity system, once dominated by British rock stars, has now passed to sport).

The paradox of stardom is that an individual hungers for the success that destroys him. Bowie tried to deal with this, and perhaps his personal shyness too, by adopting a series of personae. The earlier ones were extremely androgynous and their extraordinary success spearheaded a sexual sea change: for the first time since the classical age, homosexuality became unashamedly part of mainstream culture. Consequently, he has been turned into a patron saint of the gender-bending revolution. Though heterosexual, Bowie was intensely drawn to the catalytic powers of ambivalence, theatricality, experiment and outrage.

In this show he is described as the most influential rock star of all time, but the results of that influence are not demonstrated. A few years ago he expressed some regret at his public avowals of bisexuality, saying that they delayed acceptance in America. This is the business man talking, not the artist.

It is always disappointing when an artist seems to reject something ground breaking that put him on the map. It is characteristic, however, that Bowie doesn’t wish to be identified with anything at a personal level, and indeed the current exhibition is about how to avoid being seen by being totally in-your-face.

Around its walls are numerous rather severe captions completing the sentence “David Bowie is…quite aware of what he’s going through/watching you/wearing a mask of his own face/an intervention/moving like a tiger on Vaseline etc”. In establishing anonymity, this continuo strives strenuously for mystique and lacks depth or humour. I would like to have seen some additional lines such as “David Bowie is taking drugs/is terrified of flying/can’t think what to do next . . .”

The introductory white room has the cramped charm of an electronic toyshop. Over shoulders and between heads, you see bits of the earlier life arranged in clever ways but I often discarded the interactive headset as an obstacle to engagement.

The second, black room is much larger and is in the form of a nightclub. There is height for grand projections and the one here is triumphant: over walls of embedded, flashing costumes, Bowie and his band perform “The Jean Genie” in movie montage through a right-angle, with real headset-free sound, to remind us that, whatever else he is, he’s a natural rocker too. Round about are cabin-like subspaces full of relics and delicious electronic displays, many cross-synchronised.

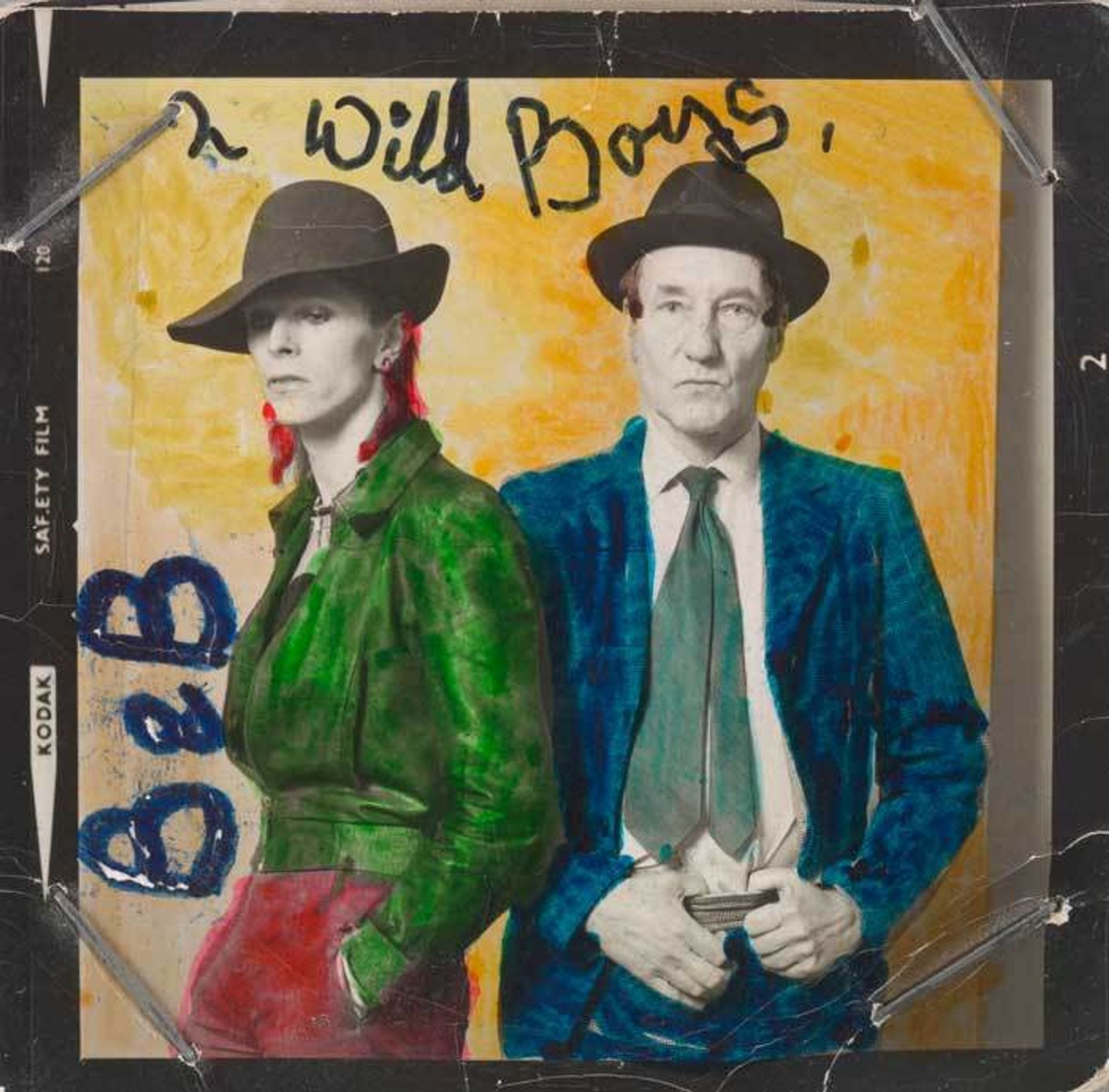

Time is a great de-kitsch-er, and the costumes throughout are superb, much better than I remember (eg; Pierrot by Natasha Korniloff; the Distressed Frock Coat by Bowie himself). The photographs, designs and videos are very striking too; he looks vaguely unpleasant in all of them, with a citric edge that is part of his magnetism.

The recorded songs, dissolving the boundaries of rock and pop, soul and electronica, with lyric flavours from honky-tonk to William Burroughs, surge in and out of one’s attention, sometimes with, sometimes without, the headset. Sturdy, gorgeous, and haunting, they are so emblematic of Bowie that nobody else can record them.

The exhibition gets better the longer you stay: move round and about, backwards and forwards, enjoy the fun of the fair, a couple of hours pass. Then suddenly it stops getting better: it’s so self-referential; everywhere you look you are being told David Bowie is this or that; it’s a shrine to an idol; it’s centripetal, too small. You have to get out!

• Duncan Fallowell’s How To Disappear won the 2012 PEN/Ackerley Prize for memoir. He was also The Spectator’s first rock critic and has worked extensively with the avant-garde German experimental rock band Can.