A four-year war for control of Natalia Goncharova’s artistic legacy showed no sign of ending during London’s recent Russian Art Week (27 November-4 December).

At a conference on 2 December on the forgery of Russian avant-garde art, Konstantin Akinsha, a historian and journalist, highlighted the widespread faking of works attributed to Goncharova (1881-1962) and others. He cited alleged collusion by international experts, including curators, and criminal investigations in countries ranging from Finland, Sweden, Switzerland and Germany to Russia itself.

Chairing a session at the Gallery for Russian Arts and Design, James Butterwick, a London-based dealer, said it was “no exaggeration” that nearly 95% of 1901-13 “Goncharova” oil paintings on the market were fakes. Butterwick is a member of the Moscow-based International Confederation of Antique and Art Dealers. “It’s common knowledge that the Russian art market is inundated with forgeries,” Butterwick said.

Scathing attack

Butterwick also quoted a scathing attack by Irina Vakar, a curator at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, the holder of Goncharova’s archives. In 2011, Vakar and others publicly challenged the English art historian Anthony Parton and the French catalogue compiler Denise Bazetoux over their publications on Goncharova. Parton and Bazetoux are both members of the International Chamber of Russian Modernism, a Paris-based group of art historians.

Butterwick’s comments were the latest in a series of challenges since 2011, when Bazetoux published the first volume of a planned three-part catalogue raisonné and was attacked in the Russian art press as having falsely authenticated multiple alleged forgeries.

The conference offered no platform to Parton or Bazetoux. “After all the problems with the Russian avant-garde, I’ve taken my distance and prefer to devote my time to other painters,” Bazetoux told The Art Newspaper in an email. Parton did not wish to respond to questions about the situation.

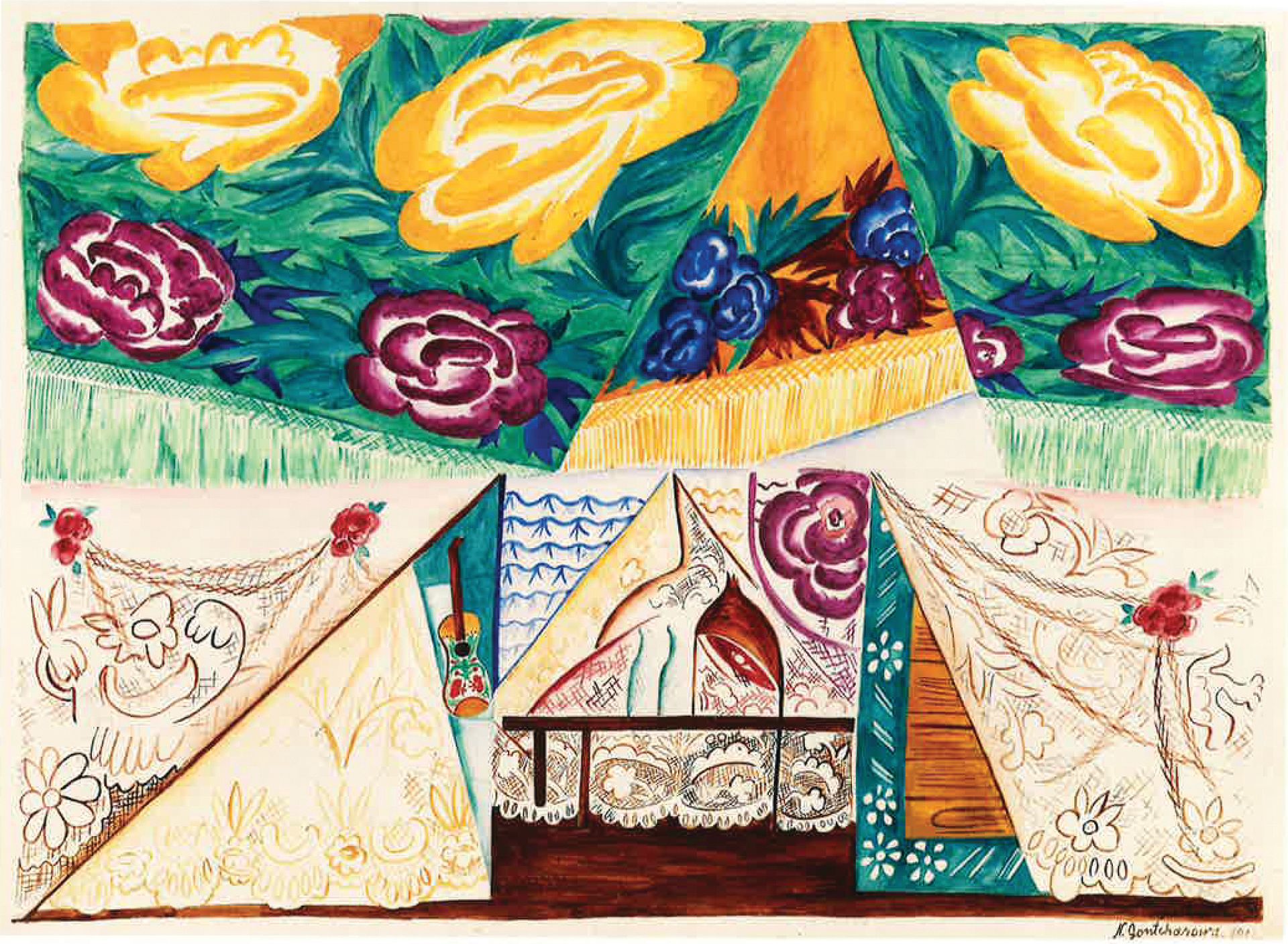

Underlying the fracas is the particular history of Goncharova. Born in 1881, she was recognised early as a key and prolific driver in the development of a distinctively Russian Modernist art, fusing European and other popular traditions; in 1913, her solo retrospective in Moscow comprised almost 800 works. But Goncharova left Russia for Europe in 1915 to work as a designer for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and after the 1917 revolution, her earlier work was consigned by Stalin, together with other avant-garde art, to bourgeois oblivion. She died a pauper in Paris in 1962.

Rediscovery and market rise After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Goncharova’s work emerged from obscurity and her reputation soared. The auction sales of Les Fleurs (around 1912) for £5.5m in 2008 and L’Espagnole (around 1915) for £6.4m in 2010 made her, at the time, the most expensive female artist at auction.

With so much money at stake, Goncharova’s market rise triggered a spate of previously uncatalogued works flowing from private collections—and a commensurate spate of faking allegations. “It’s not just the Russian avant-garde,” Akinsha told The Art Newspaper at the conference. “When you have art with a broken provenance, on the cusp of rediscovery, this happens.”

Goncharova disappoints at auction

Flagged as the highlight of Sotheby’s Russian Week pictures auction (London, 1 December), a group of more than 250 works by Natalia Goncharova (and some by her husband, Mikhail Larionov) did not sell well. Online bidders kept some action going but only 43% of the lots sold, for a modest hammer price of £430,100 (premium £537,625; est £942,000). The unsold lots included one of Goncharova’s designs for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes: Set Design for Espagne or Triana (1916, est £30,000-£50,000).

Sotheby’s said that the disappointing result was not due to the concerns over authenticity that plague the Russian avant-garde market. Some dealers agreed. “There’s too much of her stuff out there, and not enough buyers,” said James Butterwick, a Russian avant-garde specialist, adding: “She wasn’t the same artist after she left Russia [in 1915].” The works that were offered dated from this time.