Marc Spiegler, the director of the Art Basel fairs, believes that art dealers may need to be more transparent about pricing if they are to compete with the auction houses. In a presentation prepared for the Talking Galleries conference in Barcelona in early November, Spiegler said that the fact that auction houses provide the only publicly available prices for art means that the market is “at [their] mercy”. In this way, the auction houses have been allowed to “define what is and isn’t important”, he said.

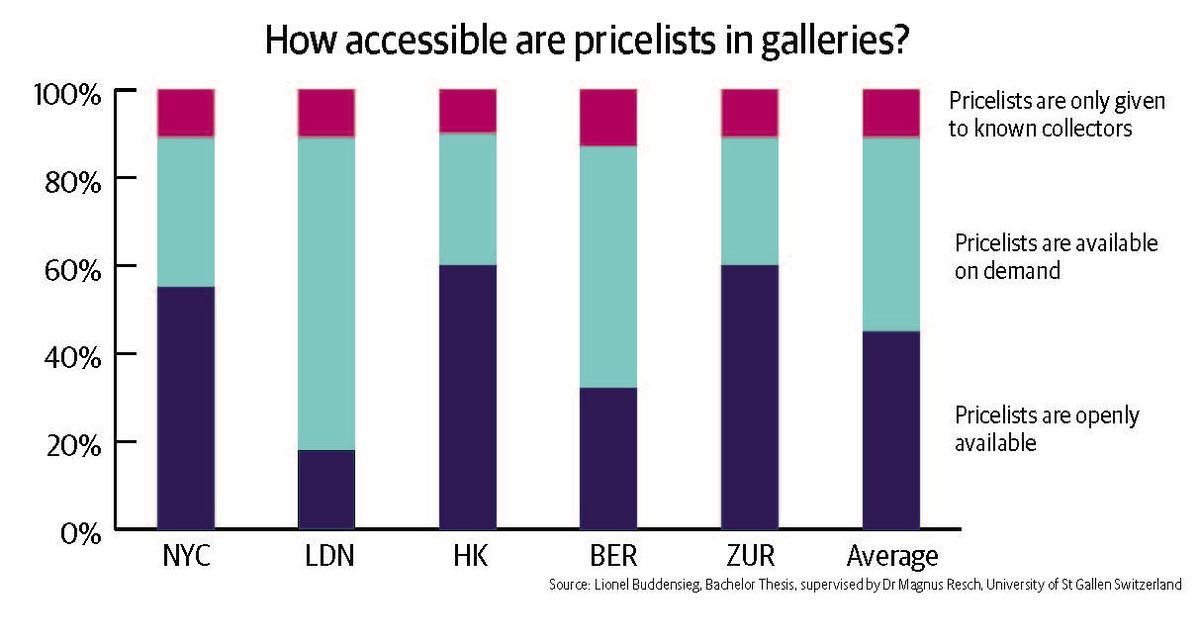

Meanwhile, data compiled by the author and art market researcher Magnus Resch, with the University of St Gallen, Switzerland, suggests that galleries are yet to heed the warning. Resch’s analysis of 400 galleries in New York, London, Hong Kong, Berlin and Zurich shows that price lists are openly available in fewer than half of spaces.

“Imagine walking into a shop on Fifth Avenue and asking the price of a Hermès handbag and getting the reply: ‘I won’t tell you.’ It’s not only embarrassing for the person asking but it’s also destroying potential business opportunities. Price transparency is still the holy grail in the art world,” Resch says.

According to his data, many galleries (40%) only hand out price lists on request, with 10% not doing so at all, except to known collectors. There is a marked difference regionally: in London the number of galleries where price lists are openly available is below 20%, while in New York this goes up to 55%. However, New Yorkers aren’t covering themselves in glory: the remaining 45% are flouting a 1971 state law governing all retailers to display prices “conspicuously”.

Adam Sheffer, the president of the Art Dealers Association of America and a partner and sales director at New York’s Cheim & Read gallery, was at the Barcelona conference and says that although he agrees with many of the ideas in Spiegler’s presentation, “the idea that auction houses are more transparent than galleries is false. Through hyped-up sales and increasingly enigmatic guarantee structures, auctions foster an environment of impulse-pricing and impulse-buying,” he says. “In contrast, the gallerist has a much deeper and more nuanced level of understanding of the artists they have been working with for a long time—an understanding that is reflected in the prices that a dealer sets for artists’ works. All dealers are available to answer questions about the history of an artist’s private market so the idea that auctions represent the complete, true and transparent market is significantly flawed.”

Spiegler, who acknowledged that the auction process only “seems” more transparent, argues that today’s super-elite art buyers are people who work for their money and are no longer part of a “leisure class” with time to devote to visiting commercial galleries “in Chelsea [New York] or Mayfair” every week. If galleries are “going to be successful 15 to 20 years from now, they will have to drop old ways”, he said.

He cited other habits of exclusivity that may deter today and tomorrow’s breed of buyers, including waiting lists for works and unsmiling receptionists at galleries.