Robert Gober at the Museum of Modern Art Ambition is disenchanting. Few artists know this better than Robert Gober, whose tremendous exhibition left little room for doubt about his lofty aspirations. His work, borne out of his lapsed Catholicism, is an attempt to replace the lost glory of God with manmade art. It is a losing battle, but the results—which, in this show, included a makeshift chapel anchored by a headless Christ—prove that grand failures are better than small successes.

• Robert Gober: the Heart is Not a Metaphor, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 4 October 2014-18 January 2015

Wael Shawky at MoMA PS1 Wael Shawky is not yet a supreme dramatist. The three films in this exhibition were unfortunately slow at times, especially considering the fact that their subject matter is the violence of Medieval war. Still, Shawky’s eccentric determination to dramatise the Crusades as marionette shows is evidence of a heartening seriousness. Few artists today are willing to take on such grand subjects. Puppetry and dramatic technique can be learned, but Shawky’s faith in monumental themes—that they are not only desirable, but also necessary—is a conviction that cannot be taught.

• Wael Shawky: Cabaret Crusades, MoMA PS1, New York, 31 January-7 September

Doris Salcedo at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago Doris Salcedo’s admirable retrospective cemented her reputation as contemporary art’s chief pallbearer. For 30 years, through sculptures and installations, she has been publicly mourning victims of political violence, working in a world where “war is the main event of our time”, as she once said. But Salcedo, like all serious artists, has no political ambitions. Her work cannot and will not change the world, and she is willing to admit it. Instead, her show in Chicago did something much simpler: it made sorrow into its own reward.

• Doris Salcedo, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 21 February-24 May

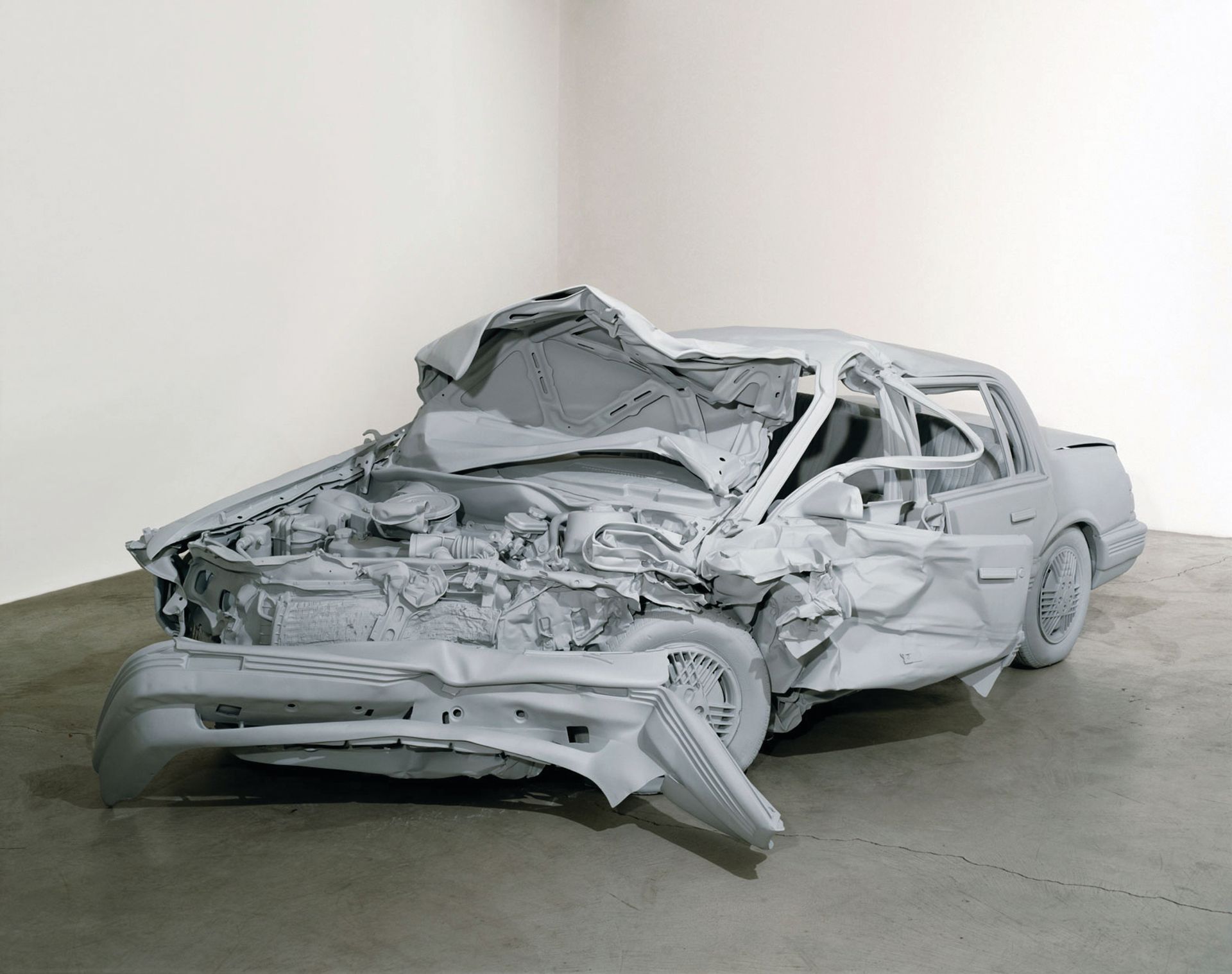

Charles Ray at the Art Institute of Chicago Morality demands that everything be put in context, but art allows for the opposite, for abstraction and deliberate myopia. Among figurative sculptors, Charles Ray is the foremost champion of this principle. He sees the world in terms of form and scale, delightfully indifferent to etiquette. Among the works in this excellent survey was a sculpture of a wrecked car, for which the model was a Pontiac Grand Am in which the driver was killed. Ray’s work—and not just this piece—takes things out of ethical context so that we can see them more clearly.

• Charles Ray: Sculpture, 1997-2014, Art Institute of Chicago, 15 May-4 October

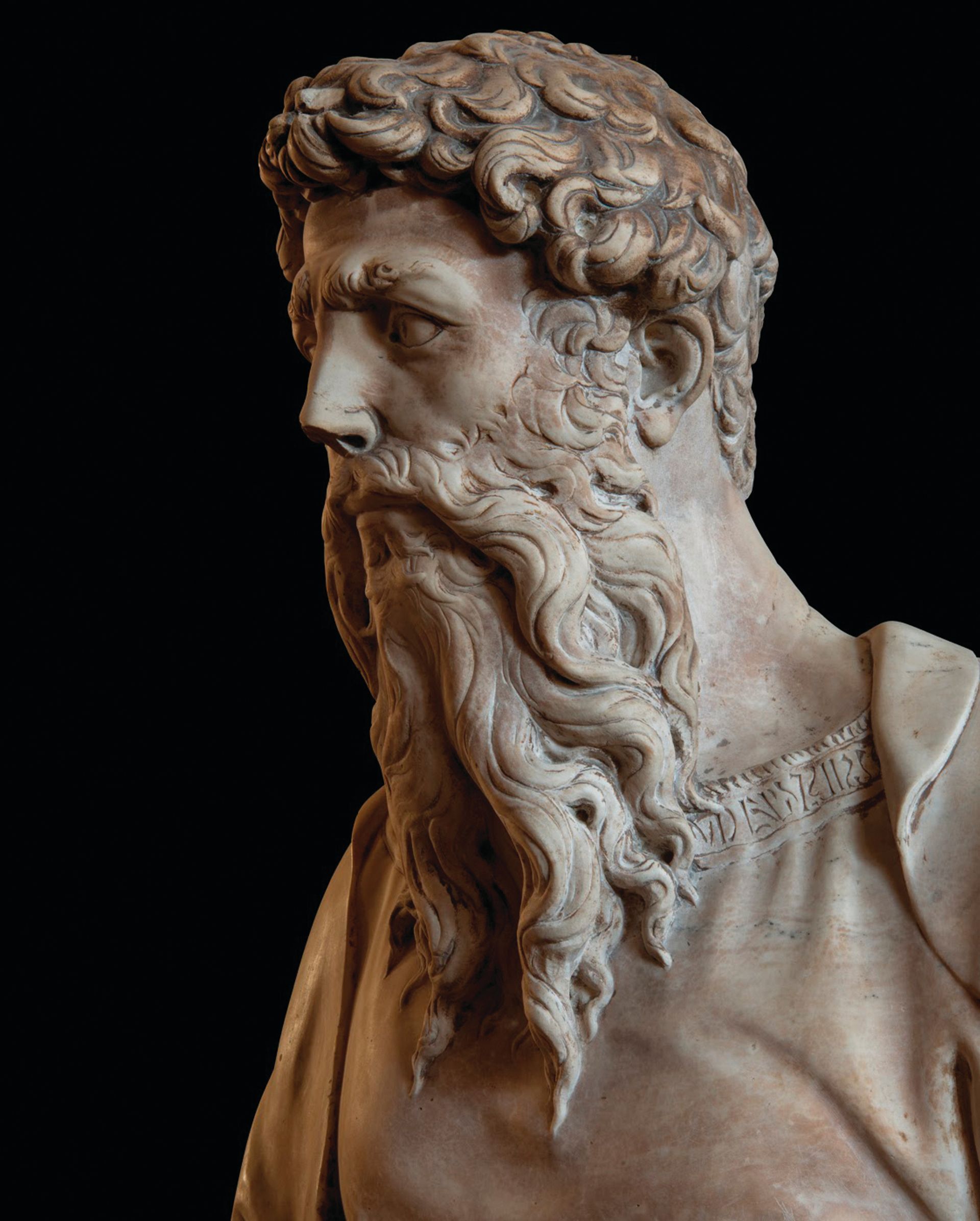

Early Renaissance at the Museum of Biblical Art New York’s Museum of Biblical Art triumphed with this splendid exhibition, which assembled 23 early Renaissance masterpieces from Florence. The show was a curatorial coup: while the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence closed for renovations, works by Nanni di Banco, Brunelleschi, Luca della Robbia, Donatello and others were sent overseas for the first time. The exhibition drew more than 20,000 visitors, but that alone was not enough to keep the museum open. Amid financial difficulties, it closed—having opened just ten years earlier— at the end of the show’s run.

• Sculpture in the Age of Donatello, Museum of Biblical Art, New York, 20 February-14 June

Goya at the National Gallery Today, Goya is most admired for his nightmarish visions and searing satire, but this captivating show at London’s National Gallery reveals how the artist channelled his ability to scrutinise his subjects into the exceptional portraits for which he was most renowned during his lifetime. In Goya’s portrayals of kings, queens, courtiers, friends and family, as well as himself, we repeatedly see him turning official portraiture upside down by making it about his subjects rather than their role in society, which brings an extraordinary parade of individuals back to life.

• Goya: the Portraits, National Gallery, London, until 10 January 2016 (opened 7 October)

Joseph Cornell at the Royal Academy of Arts Not only did this beautifully curated show bring together many of the best of Joseph Cornell’s enchantingly mysterious caskets, but its dimly lit, labyrinthine layout also enabled total immersion in what Mark Rothko described as the “uncanny magic” painstakingly conjured up by this quiet man from Queens, New York. A particular surprise was Cornell’s 1930s montaged films, made in the same spirit as his boxes, by splicing together seemingly humble and inconsequential fragments to make something altogether strange and miraculous. A dreamlike experience: hard to categorise, difficult to forget.

• Wanderlust, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 4 July-27 September

Sonia Delaunay at Tate Modern This was a timely and exhilarating celebration of a one-woman powerhouse who paved the way for so many by making no distinction between her vivid, colourful abstract paintings and her equally outré fabric, fashion and interior designs. They were given equal billing in Tate Modern’s excellent and comprehensive show, which succeeded in capturing the energy and excitement that Delaunay felt as she sought to express the dynamic spirit of modern life through her work, including poem-dresses for the Dadaists, costumes for the Ballets Russes and glorious paintings.

• Sonia Delaunay, Tate Modern, London, 15 April-9 August

Guido Guidi at Large Glass Luminous and exquisite but also rigorously objective, Guido Guidi’s photographs of a single patch of sunlight moving over the course of a day around the derelict, damp-stained interior of an abandoned gardener’s hut in Northern Italy were a revelation. I didn’t know the work of this Italian photographer, who has spent a lifetime scrutinising dusty street corners, abandoned buildings and vacant lots in and around his hometown of Cesena. This limpid record of light shifting and time passing, shown at Large Glass gallery, was a quietly powerful, irresistible introduction.

• Guido Guidi: from the Interior, Large Glass, London, 24 April-3 July

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at the Serpentine Gallery Walking among Yiadom-Boakye’s often larger-than-life paintings was an intense experience. The psychologically complex impact of these lushly rendered, predominantly black men and women made it all the more difficult to believe that not only are they all fictitious subjects, but that each of these oil paintings was completed in a single day. Yet this very urgency feeds into their power and vivacity, as does Yiadom-Boakye’s engagement with art history, especially with grand painted portraiture—a genre traditionally populated by white faces.

• Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Verses after Dusk, Serpentine Gallery, London, 2 June-13 September