Ellsworth Kelly, the pioneering American abstract painter and sculptor, died on 27 December 2015 at his home in Spencertown, New York, aged 92. His work, which steadily evolved over the course of a rich career of nearly 70 years, deftly drew on European avant-garde traditions in the service of a new American art.

Kelly was born on 31 May 1923 in Newburgh, New York. His family moved often. Between the ages of six and 16, they lived in nine different homes. “Every year my mother found a better house, so we’d move,” Kelly later told Barbaralee Diamonstein. By 1929, they had at least settled on a town: Oradell, New Jersey. There, Kelly attended junior high school and drew cover illustrations for Chirp, the school’s literary magazine.

Drama, however, was his first great love. A theatre teacher encouraged him to recite Shakespeare, partly as a way to overcome his stammer. He became a good enough actor to earn a scholarship for undergraduate study, but his parents rejected the idea. They reluctantly agreed to allow him to attend art school instead—but only if he studied commercial illustration, which at least was practical.

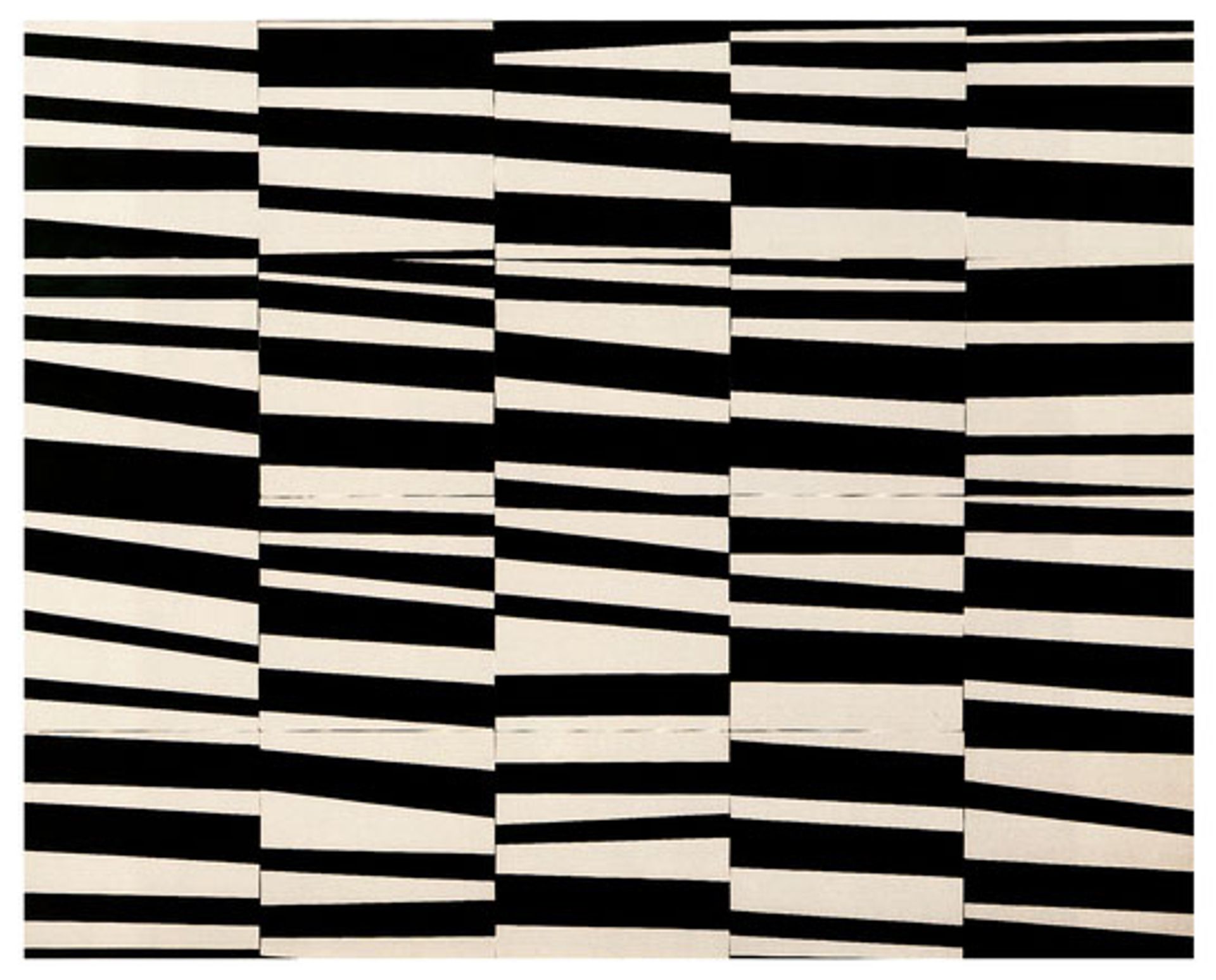

Kelly enrolled at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, in 1941, but university life was brief. The young artist, eager to join the war effort, enrolled in the military after only three semesters. On 1 January 1943, he was sent to Fort Dix, New Jersey, for training. Hoping to put his eye to good use, he requested and was granted a position with a camouflage battalion that was later attached to the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops. “We fabricated fake rubber tanks, jeeps and large guns that were inflated by compressors, which even from a short distance looked like the real thing,” Kelly later remembered. In the military, he learned a lesson that would carry through some of his great work: how to confuse figure and ground, a tactic he employed in works like Cité and Meschers, both from 1951.

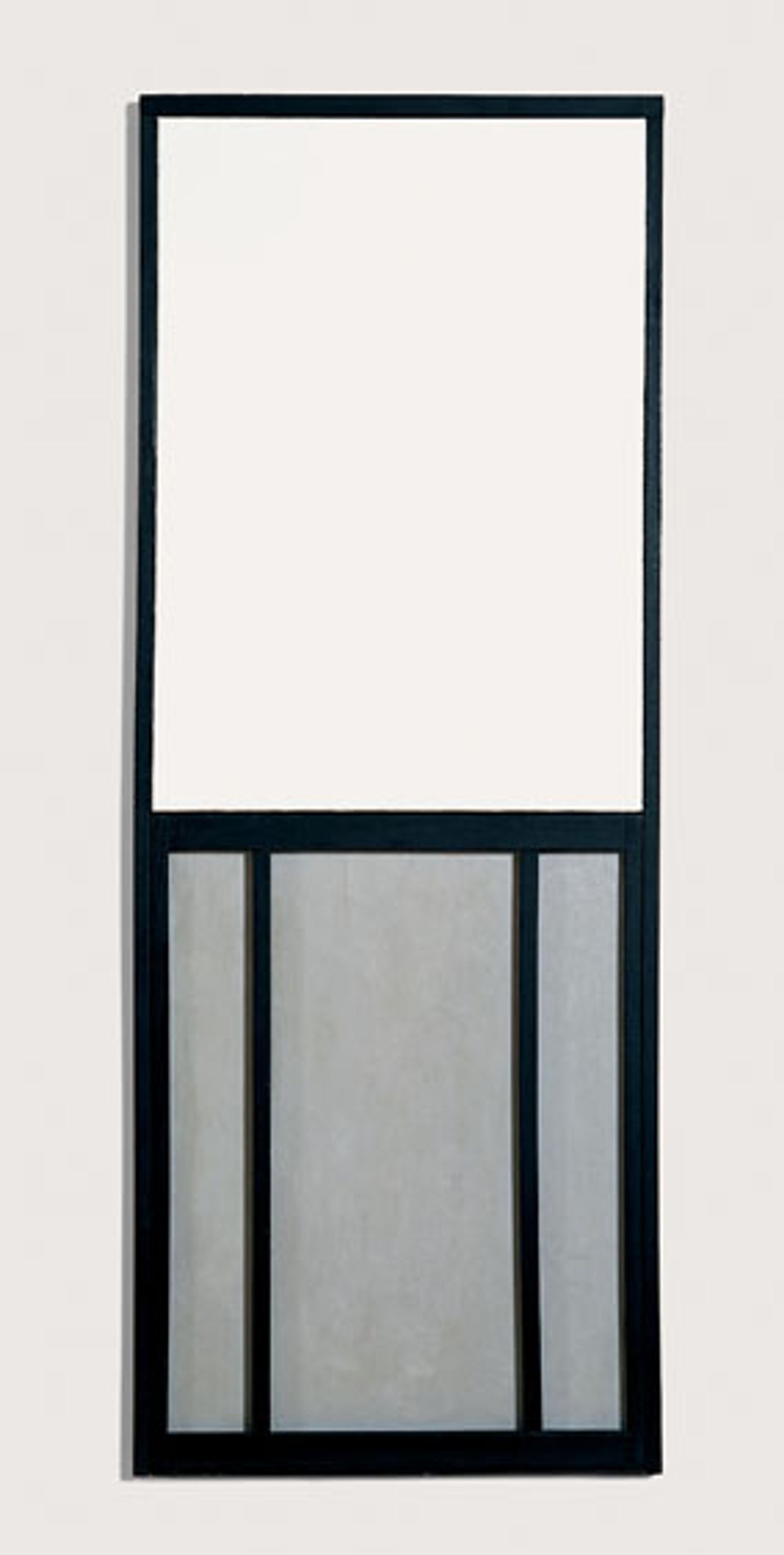

At the end of the war, Kelly settled briefly in Boston between 1946 and 1948, but his love of Modernism led him to seek out its cradle. In October 1948, he moved to France. He enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where, ostensibly, he studied academic figure drawing. But his real training was in the streets and museums of Paris. In 1949, he visited Paris’s Museum of Modern Art and was enchanted by one of its windows: a perfect rectangular shape, something he could recreate exactly in his studio. The resulting work, Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris (1949), was made in the throes of a great discovery: that art did not have to be creative. “Instead of making a picture that was an interpretation of a thing seen, or a picture of invented content,” he later wrote, “I found an object and ‘presented’ it as itself alone.”

Yet the years in Paris were only privately fruitful. Kelly had little success with French audiences. He sold only one picture during his entire stay. Although he earned some notice from critics like Michel Seuphor, he winced at the comparisons being made between his work and Piet Mondrian’s. Kelly was no grand theorist of theosophy like Mondrian—he was an American pragmatist whose time in France was running out. Exhaustion set in and towards the end of his stay, he was hospitalised for jaundice just as the G.I. Bill money that supported his trip was drying up. It was time to move on.

A return to the US When Kelly got to New York in 1954, he had to start over. He was unfamiliar with Abstract Expressionism. Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko: Kelly had heard the names and had seen their work in reproduction, but he had little idea what conversations raged in the Cedar Tavern. Nor could he have. He was part of a younger generation, one drawn to a cooler vocabulary. “In my own work,” Kelly wrote some years later, “I have never been interested in painterliness (or what I find is) a very personal handwriting, putting marks on canvas.”

Kelly moved to Coenities Slip in downtown Manhattan in 1956, where he became friendly with James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney and especially Agnes Martin. His earliest work from the period—a group of multi-panel, monochrome canvases—were based on ideas he carried over from France. But he was eager to shed his French associations for fear of being labelled a Constructivist. After his first solo show in New York, at the Betty Parsons gallery in 1956, Kelly shifted gears to a seemingly more traditional kind of work, with abstract figures set against clear grounds. Here were pictures that set him apart not only from Piet Mondrian and Kasimir Malevich, but also from Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline.

Works of this period were full of productive contradiction: they spoke in the grand language of abstraction but still carried Kelly’s particular accent. This was confusing to critics: how exactly was Kelly to be categorised? Curators in particular battled over his work by including it in exhibitions with all kinds of different agendas. Kelly was called a contemporary traditionalist (in the show Modern Classicism at the David Herbert Gallery, 1960); a cousin of the New York School (American Abstract Expressionists and Imagists at the Guggenheim Museum, 1961) or one of its sons (Post-Painterly Abstraction at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1964); a mathematical abstractionist (Geometric Abstraction in America at the Whitney Museum, 1962); a Minimalist (Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum, 1964) and even an Op artist (The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art, 1965).

Curators beckoned and Kelly’s work wandered in any direction they called. But New York was a pressure cooker and not everyone was generous. Heading through the 1960s and into the 1970s, Kelly stumbled through a group of paintings and sculptures that critics savaged. In a review of Kelly’s exhibition at the Sidney Janis gallery in 1971, Hilton Kramer wrote: “I frankly find it very difficult to remain interested in pictures of this sort for more than about three minutes.”

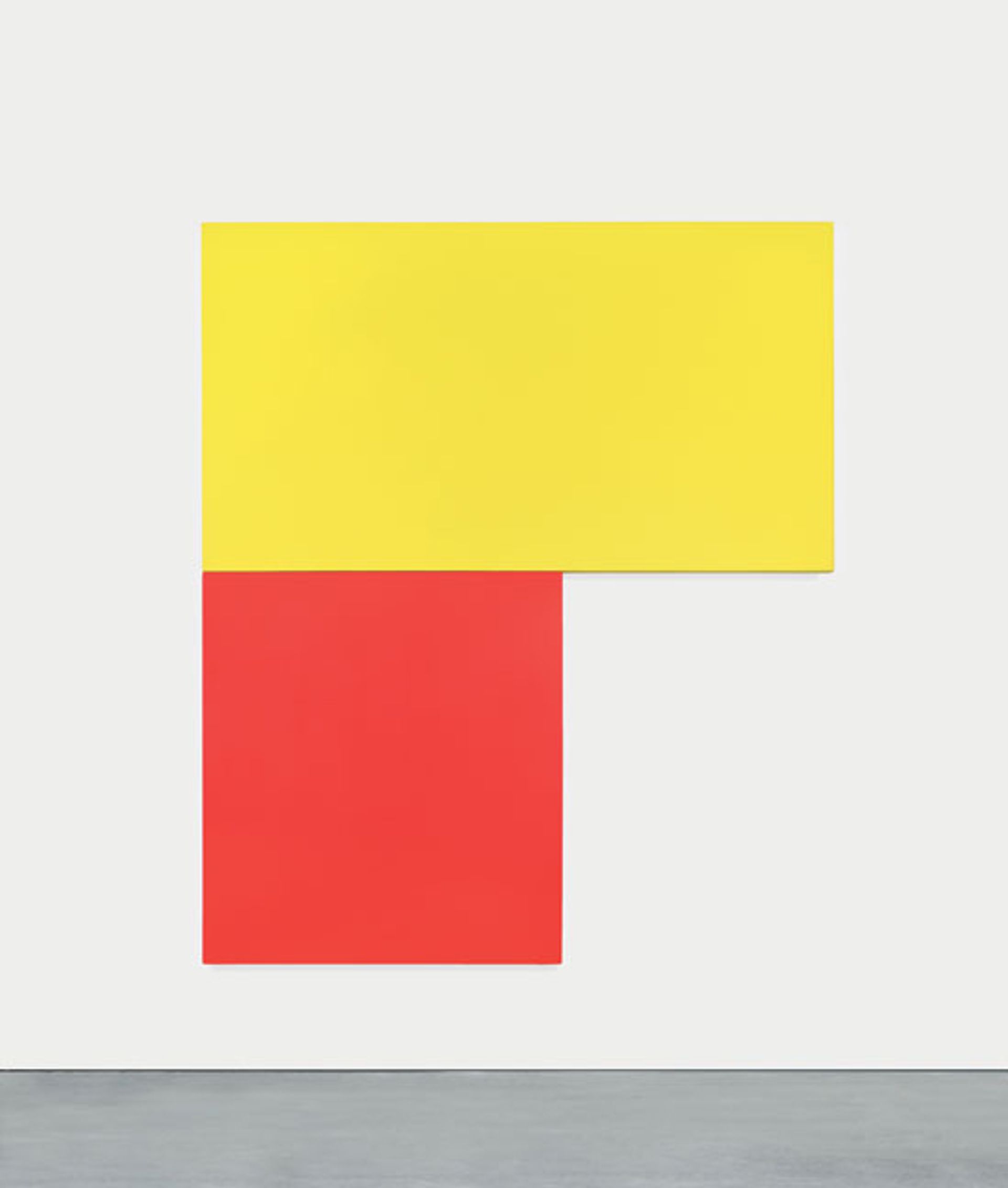

Chatham: a turning point In 1970, Kelly left the city and bought a Victorian house on a winding road in Spencertown, New York. He rented a studio in the nearby village of Chatham for $50 a month from the local barber. Here, with room to breathe, Kelly developed a group of 14 L-shaped pictures in 1971 titled the Chatham series. These paintings, with their missing corners, teetered carefully, as if they could slip off the wall at any moment. Gone was any specious belief in permanence, in art that would “exist forever in the present”, replaced by a newfound understanding that instability too had a role to play.

When the paintings were exhibited together at the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo, New York, in 1972, they signalled a triumphant return. Critics warmed to Kelly’s embrace of vulnerability. This time, Hilton Kramer wrote a glowing review in the New York Times. The artist, he wrote, was one of the “most audacious” abstract painters working at the time and the Chatham works were called “the very best pictures Kelly has produced.”

Kelly carried his interest in volatility through the 1980s. In 1984, he presented a group of 14 aluminium and steel reliefs at the Leo Castelli and Margo Leavin galleries in New York and Los Angeles. Although each work was attached to the wall, each also had one edge on the ground, as if they had slipped. Here was a deeper acceptance of entropy, a recognition that even firm slabs of metal were bound to fall.

And yet it seemed like Kelly himself would never fall; his pace was remarkable. Earlier this year, at the Matthew Marks Gallery in New York, he presented 14 new paintings and four new sculptures that looked like barely anything else he had ever made. Works like Blue Relief over Yellow (2014), with its oblong figure-eight pressed against a bright yellow ground, re-configured how we see the artist’s work.

The ability to continue developing his art through his early 90s spoke to Kelly’s unbridled optimism. In November 2014, when I met him at his studio in Spencertown, his enthusiasm for the future was palpable. Kelly had a deep reverence for the past—he spent much of the day telling me about his love of Monet and showing me his collection of work by Francis Picabia, Willem de Kooning and Blinky Palermo—but his hopes lay ahead.

In a rare moment of doubt, he expressed concern over climate change and political instability, saying that “serious people are afraid we’ve had it, that we’re done.” But then, without hesitation, he added: “But I feel like I can’t live that way. I’ve got to not let it annoy me, because we have produced great art. I don’t know if you read [the US author William] Faulkner, but when he won the Nobel prize [in 1949], he said: ‘I believe that man will not merely endure, he will prevail.’” Which is precisely what Kelly did.