1. Has the market reached its peak? The art market was valued at €51bn in 2014, according to Clare McAndrew’s 2014 Tefaf Report, driven predominantly by demand at the top end. Blame the “battle of the billionaires”—the super-wealthy vying for a small handful of top works of art by the Modern masters Picasso, Giacometti, Rothko, Freud and Warhol.

The top-heavy nature of the market has persisted into 2015 and to the list must now be added Amedeo Modigliani, whose sexy and enticing Nu couché (1917-18) achieved the second-highest auction price ever in New York when it sold for $170.4m to the Chinese billionaire Liu Yiqian at Christie’s 9 November sale, The Artist’s Muse. The sale, which achieved $439m hammer ($491m with fees), fell below the pre-sale expectations of $440m to $545m. And this was the story all through the ten-day New York November sales marathon: most of the auctions failed to achieve their low estimates.

This was the third edition of Christie’s new hybrid auctions, which mix Impressionist, Modern and contemporary art, to be held in New York, and it fell far short of the sparkling results achieved on 11 May, when the firm sold $705m worth of art and achieved $179m for Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger, Version 0 (1955) and $141m for Giacometti’s L’homme au doigt (1947).

The use of guarantees (see below) further stimulated the market in 2015, giving vendors no reason for caution, since the risk was carried by the auction house or a third party. However, art market insiders have long felt that the market was too “bubbly” and due a correction, which promptly showed in the November results.

To say the market is in trouble would be an overstatement: the autumn saw strong sales in the London auctions, and $2.3bn of art sold in the New York sessions. However, with a rise in interest rates on the horizon, chaos in the Middle East, political unrest in many countries and a cooling Chinese economy, it is hardly surprising that the art market, finally, has started cooling as well.

2. Guarantees in overdrive The cut-throat competition between the auction houses has led to an increasing reliance on guarantees. The most notable was the $515m promised by Sotheby’s for the Taubman estate, but these financial instruments were widespread elsewhere too. Phillips guaranteed almost half its 8 November sale in New York; Christie’s backed, either itself or through third parties, 18 works in its Artist’s Muse sale and ten in its post-war and contemporary art sale on 10 November. Although the auction houses deny it, the use of guarantees, coupled with the perception of art as a safe refuge for cash as well as an increasingly mainstream investment vehicle, was a notable element in inflating the market this year.

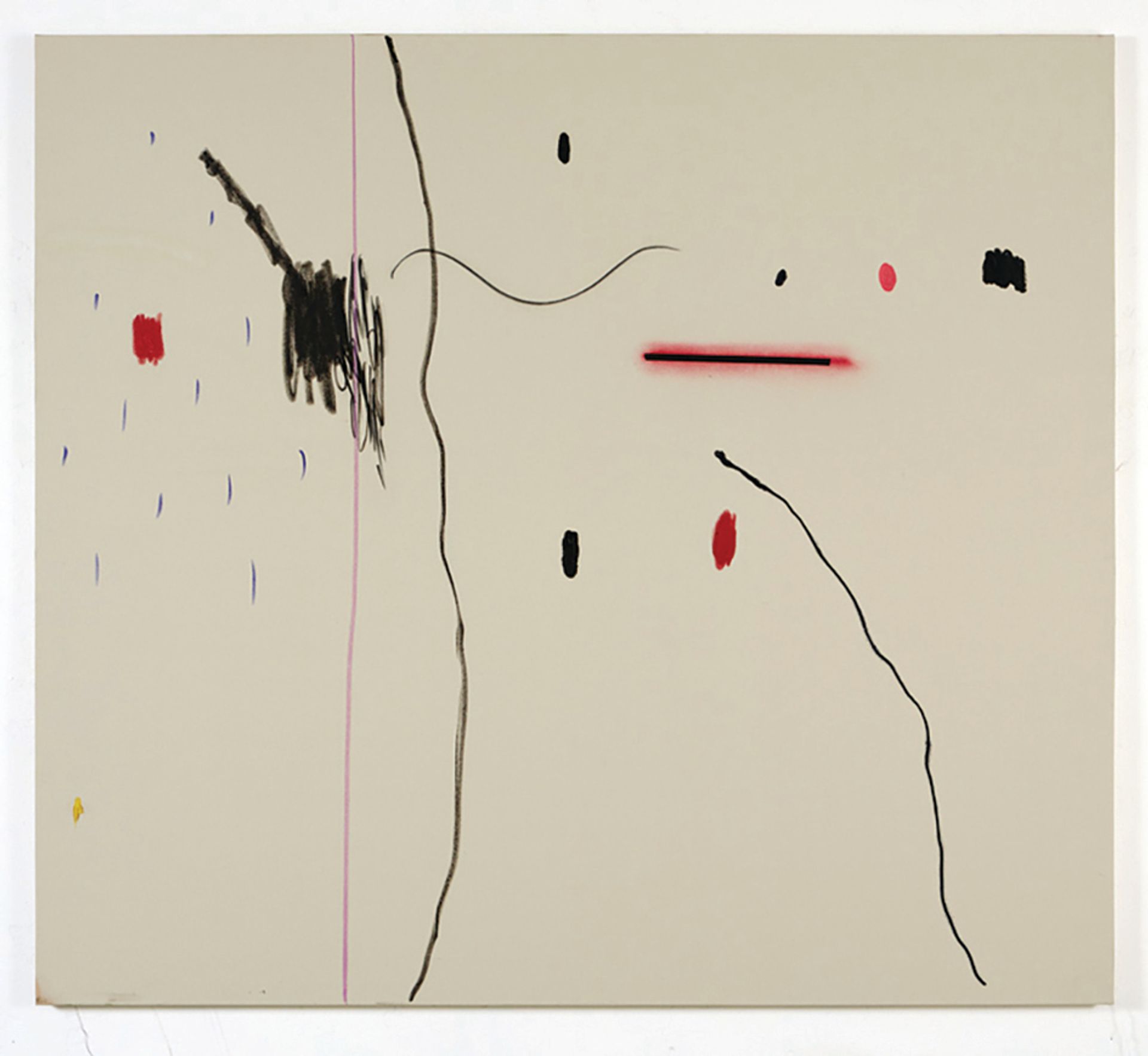

3. Zombie formalism is dead On the other hand, the heat went rapidly out of the market for some names that had seen highly speculative purchases just a year before. Zombie formalism is the term sometimes used to describe works by artists such as Lucien Smith, David Ostrowski, Parker Ito, Dan Rees and Christian Rosa, whose prices had soared in 2014. This year saw a definite correction. Just one example was Rosa’s Endless refill (2013), which sold for $12,500, well under its $20,000 to $30,000 estimate, at Christie’s New York sale in September; two other works were bought in at Phillips’ New Now sale in New York in the same month. It was a far cry from the $209,000 that his Untitled (2013) achieved at Christie’s New York sale in November 2014.

4. The “curated” sale The year also saw a continuation of the formula introduced by Christie’s in November last year: Modern, Impressionist, post-war and contemporary works of art were offered together in “curated” sales. Phillips followed suit, moving out of its chosen niche of the newest contemporary art and into the Modern market. Its inaugural 20th-century and contemporary art sale in New York in November saw works by De Kooning, Le Corbusier, De Chirico and Calder achieve the top prices.

The changes were not just for Modern art, and Christie’s moved its December sales in New York to early April, combining them into a new “Classic Art Week”, which groups Old Masters, antiquities, sculpture and decorative art. Again, the top lots have been put in their own special sale, which includes paintings, drawings, sculpture and photography from the 18th to the 20th centuries.

Some commentators saw these combined-category sales as a means of disguising weaknesses, with Christie’s having lost out to Sotheby’s in the Impressionist and Old Master fields in the past few years. Christie’s maintains that the change is in response to the cross-collecting tastes of its clients.

5. Uncertainty in Asia Dealers and auctioneers continued to fret about the contraction of the art market in China, which from its peak in 2011 (admittedly based on unreliable figures) had fallen by more than 30% by the end of 2014, according to a report by Artnet and the China Association of Auctioneers.

The figures for sales in spring and autumn in Hong Kong were by no means catastrophic, but they continued to decline. In the spring round of sales this year, Sotheby’s tally dropped by 20%, with $339m worth of art sold in 2015 compared with $425m in 2014. Things were considerably less drastic this autumn, when the Sotheby’s Hong Kong season raised $335m compared with $366m in autumn 2014.

However, observers qualified the sales as lacking energy and results were patchy. Strong sessions, such as the specialist Gutai art sale, which was 100% sold, were tempered by weaker ones, such as the South East Asian art sale, which had a 62% sell-through rate.

As for Christie’s, its spring sales were $411m this year, up on the previous year’s $378m. Results from its autumn series were not available as we went to press.

Even so, Chinese buyers did step up to the plate in Western auctions this year, acquiring works by Monet, Van Gogh, Modigliani and Picasso at sometimes eyebrow-raising prices: Monet’s Bassin aux nymphéas, les rosiers (1913) for $20.4m (Sotheby’s, New York, 5 May 2015); Van Gogh’s L’Allée Des Alyscamps (1888) for $66.3m (Sotheby’s, New York, 5 May 2015); and Modigliani’s Nu couché (1917-18) for $170m (Christie’s, New York, 9 November 2015).

6. Calls for transparency Until very recently, the art market was perceived as totally unregulated—not entirely correctly, as normal consumer protection laws apply widely, and many countries have regulations covering art and auction sales. Nevertheless, the secrecy of the art market, plus problems of valuation and authentication, means that it remains opaque enough to facilitate wrongdoing. This year, for the first time, regulators in Belgium and, more importantly, Switzerland, started taking an interest in the art trade specifically because of the risk of money laundering and tax evasion or avoidance.

Tying neatly into the subject were increasingly juicy revelations during the bitter and ongoing battle between freeport owner Yves Bouvier and his former client, Dmitry Rybolovlev. It emerged that no less than $2bn of art had been traded, some through offshore entities and trusts, over the past eight years, with no public knowledge of the transactions. Indeed, many art-world insiders had not known until then that Bouvier was an art dealer as well as a shipper and owner of storage facilities for art.

Will things change or will the regulators lose interest? Most players hope the issue will quietly go away, but as Melanie Gerlis (one of the two art market editors of The Art Newspaper) noted during a panel at the Arts Club in London, in October, the trade can’t have it both ways: if it wants the market to grow, with ever higher volumes and values, and art transformed into an asset class with dedicated investment funds, then it will have to accept that better regulation is a necessity. How that can be achieved is another matter entirely.