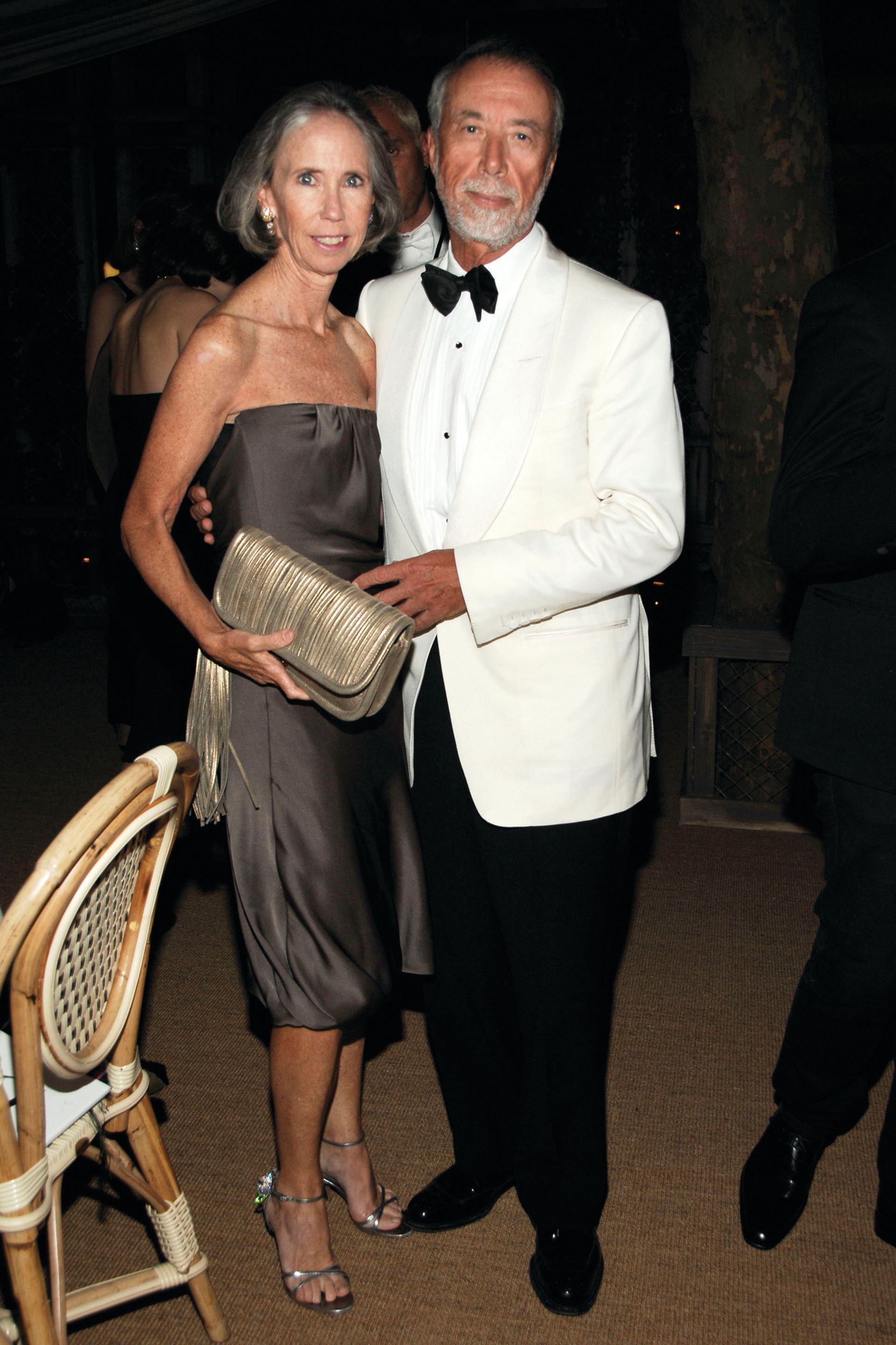

US judge Paul Gardephe is considering nearly two dozen motions of enormous consequence for the first trial in the $60m Knoedler Gallery forgery scandal scheduled to begin on 25 January. The motions concern what evidence the jury will hear, and so will help influence their verdict on whether the defendants—the gallery, its former director Ann Freedman, and its owner 8-31 Holdings—should pay the collectors Domenico and Eleanore De Sole up to $25.3m for selling the couple a fake Mark Rothko painting in 2004.

The core issue is whether the defendants committed fraud. Did Freedman make false statements knowingly or with the intention of deceiving the De Soles? And were the collectors justified in relying on what she said?

No one disputes that Freedman made false statements. She sold the Rothko as an authentic work when it was actually painted by the artist Pei-Shen Qian and its provenance fabricated by the art dealer Glafira Rosales, who sold around 30 fake works to Knoedler.

The De Soles argue that Freedman must have known the works were fake: Rosales was selling Knoedler works at far below their market value; there were no documents; and the provenance shifted.

The defendants will argue that Freedman believed the works to be genuine. She has previously argued that experts “unambiguously conveyed” to her that the works were authentic, citing more than 50 internal Knoedler Gallery memos, which she claims record the favourable reactions of various experts to the Rosales-supplied paintings. One note says the scholars David Anfam and Irving Sandler “examined the Rothko and the Kline” and were “unanimous” that “these paintings are… by these artists”.

The De Soles want the memos excluded as unreliable evidence. They argue that because the memos are internal gallery documents and not written by the experts themselves, they might be fraudulent. The De Soles say that in pre-trial testimony, “every independent witness… confronted with [these] statements… denied making them”.

The defendants want the judge to keep off the witness stand those experts who saw the works. Their argument is that, since Freedman believed that the experts thought the works were authentic when she says they examined them, it is irrelevant whether those experts now deny giving such opinions.

The De Soles also want Martha Parrish, an expert on dealer practice, to testify that “no responsible dealer” would have handled the paintings. The defendants have asked the judge to keep Parrish off the stand, arguing that she uses standards rejected by the Art Dealers Association of America.

Before closing in 2011, Knoedler paid the law firm Herrick Feinstein $700,000 in connection with a subpoena the gallery had received in 2009 from the FBI, which was investigating the fakes. The defendants want to keep the De Soles’ financial expert from testifying that Knoedler would have suffered a $3.2m loss from the period between 1994 (when the Rosales-Knoedler relationship began) and its closure if it had not sold the fake works. The defence says that the expert’s calculations do not include the payment to Herrick Feinstein, so the figures are wrong and should be excluded.

The De Soles will try to persuade the jury that Freedman, whose benefits included a share in Knoedler profits, also gained from selling the fakes. In her last five years at Knoedler until 2009, Freedman personally earned almost $12m, including $4.4m in 2008.

The parties are also battling over how the judge should instruct the jury on the law to apply to the evidence. One point of contention is the legal standard for evaluating whether the De Soles were justified in relying on what Freedman told them. The De Soles say they were entitled to believe her, because of Knoedler’s prestigious reputation.

The defendants argue that the collectors should have investigated the work’s authenticity themselves and have asked the judge to instruct the jury to determine whether the De Soles did “enough due diligence relative to their net worth”. The De Soles have taken umbrage at this, and say that the defendants are implying that “rich people are required to do more due diligence because they can afford it—that is wrong”.

Did Freedman try to get Julian Weissman to change his story? Julian Weissman, a former director at Knoedler, who was working as an independent dealer by the time he too sold fake Abstract Expressionist works acquired through Glafira Rosales, gave pre-trial testimony. He says that Rosales told him that Freedman had said he “should now change [his] story [about provenance], so that our stories matched”. The defendants want this evidence excluded. What matters, they say, is what led up to the 2004 sale to the De Soles, and the alleged conversation could not have occurred until 2007, when Freedman learned Rosales was also working with Weissman. In her pre-trial testimony, Freedman said Rosales didn’t discuss Weissman with her, and she doesn’t recall telling Rosales to tell him anything.