In the British Museum's latest exhibition, Egypt: Faith After the Pharaohs, there is a long fragment of papyrus, one of many on display, written in Greek and called the Gospel of Thomas. What is striking about this fragment is not its beauty or penmanship, but the era in which it was written. In Oxyrhynchus, an Egyptian city, the scroll’s Christian owner had copied the text less than 300 years after the death of Jesus, a time when the ancient Egyptian gods were still widely worshipped, before the acceptance of Christianity across the Roman Empire and before the appearance of Islam. To many of his contemporaries in Egypt, this ancient copyist—a man simply trying to preserve his messiah's sayings—would have been a rebel. He could not have predicted how Egypt, and the whole world, would change over the coming centuries, or that the church would forbid Christians from reading the very text he was copying once the contents of the New Testament had been agreed upon.

Religious development—its continuation and transformation—is at the heart of Egypt: Faith After the Pharaohs. It is what makes the show so fascinating and ambitious. Taking visitors from 30BC to AD1171, the exhibition is divided into three main sections, covering the Romans in Egypt and their interactions with the Jews and early Christians, the transition to Egypt as part of a Christian Empire and then, through the Byzantine Era, onwards into the Islamic Period. It is a millennium often ignored by museums in favour of Egypt's more ancient glories. Where most exhibitions end, this one begins.

The themes are made clear from the outset. In the first gallery, three books are displayed together: a Hebrew Bible, the oldest known copy of the New Testament and a Qur'an. These are thematically united by a 5th century amulet depicting Abraham's sacrifice, an event sacred in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Unexpectedly, however, the amulet's reverse bears an ankh-sign, the ancient Egyptian hieroglyph for life, connecting the object with a more ancient tradition. It is a simple piece that, like most of the objects on display, rewards closer examination.

From this introduction, the first section focuses on Roman Egypt, and in particular on the Roman relationship with Egyptian religion and the country's Jewish population. Local and foreign ideas were fused after Egypt's integration into the empire, represented here by striking statues of the god Horus dressed as a Roman emperor. But there was also a continuation of traditions, as shown through a stele of Diocletian, the Roman emperor dressed faithfully as a pharaoh. Beneath these outward signs of unity, tensions boiled. According to one papyrus, in AD38, a riot broke out in Alexandria, led by citizens accusing the Jewish population of failing to honour the Roman emperor. The papyrus contains the emperor's response. He allowed the Alexandrians to build statues to him and told the people to stop interfering in Jewish religious worship. It's an odd picture: Egyptian citizens, many increasingly Hellenised, living in a city founded by a foreigner, rioting because of alleged disrespect to an emperor cult imported barely 70 years earlier.

Not all interactions were as tense. A house lease contract, drawn up in AD400 between two sisters and a man identified as Aurelius Jose Son of Judas, Jew, proves the continued presence of Jews in Egypt despite ongoing hostilities. The names of the sisters also serve to highlight the fusion of cultures at the time. One was named Tayris ("She of Horus" in Egyptian), while the other was Theodora ("Gift of God" in Greek). Cultural melting pots are nothing new.

Though Judaism and Islam enter the exhibition fully formed, Christianity develops before our eyes. Texts such as the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Mary, both omitted from the New Testament, provide an insight into the early days of this evolving religious movement. A gold coin of Diocletian represents his Great Persecution of Christians throughout the empire, while the oldest known copy of the Nicene Creed—a profession of Christian faith, developed under Emperor Constantine—reflects their acceptance. The early Christians also adopted ancient imagery. Statues of the goddess Isis nursing Horus-the-Child inspired paintings of Mary and the Christ child. Ancient temple complexes were reused as churches. The appearance of Roman temples inspired Christian architecture.

Nevertheless, it is not the architectural fragments on display or the acts of emperors described that most grab the attention, but the simple emanations of devotion. What at first appears to be a crudely painted silhouette of a man in black, arms raised with gecko-hands, turns out to be a depiction of the artist praying. It is a humble symbol of faith in a recently altered religious landscape. By appealing to all strata of society, Christianity spread across Egypt, but the old ways died hard. Traditional ancient Egyptian magical practices remained in use, even into the Islamic Period. This is best represented by a Greek spell, discovered in a pot alongside two embracing wax figurines, calling upon the dead to make a woman named Euphemia fall madly in love with a man named Theon. Osiris, ancient Egypt's god of the blessed dead, is among the deities invoked.

Entering the Islamic Period, you are met with a variety of objects, many beautifully carved or painted with Arabic script. It is a dramatic shift, but a welcome one that creates a renewed energy as you enter the exhibition's final section. Among the architectural pieces from mosques, intricate carvings, glass cups and jugs, lustreware, textiles and a beautiful ivory casket, are papyrus documents and curses that represent the continuation of Egypt's magical traditions from earlier centuries. Cultures also continued to mix. On display is a Hebrew Bible written in Arabic script dated to 1005, as well as a 12th-13th century text with extracts from the Qur'an written in Hebrew script.

A particularly fascinating section is devoted to the Arab interest in ancient Egypt. One book shows an illustration of the god Horus leaning on a staff, probably copied from a temple wall. The exhibition ends with a selection of the over 200,000 texts found in a storeroom within Cairo's Ben Ezra Synagogue in 1896. Surviving the years in excellent condition, these documents date to the 11th-13th centuries AD and detail the lives of the local Jewish community, as well as their connections with the wider world.

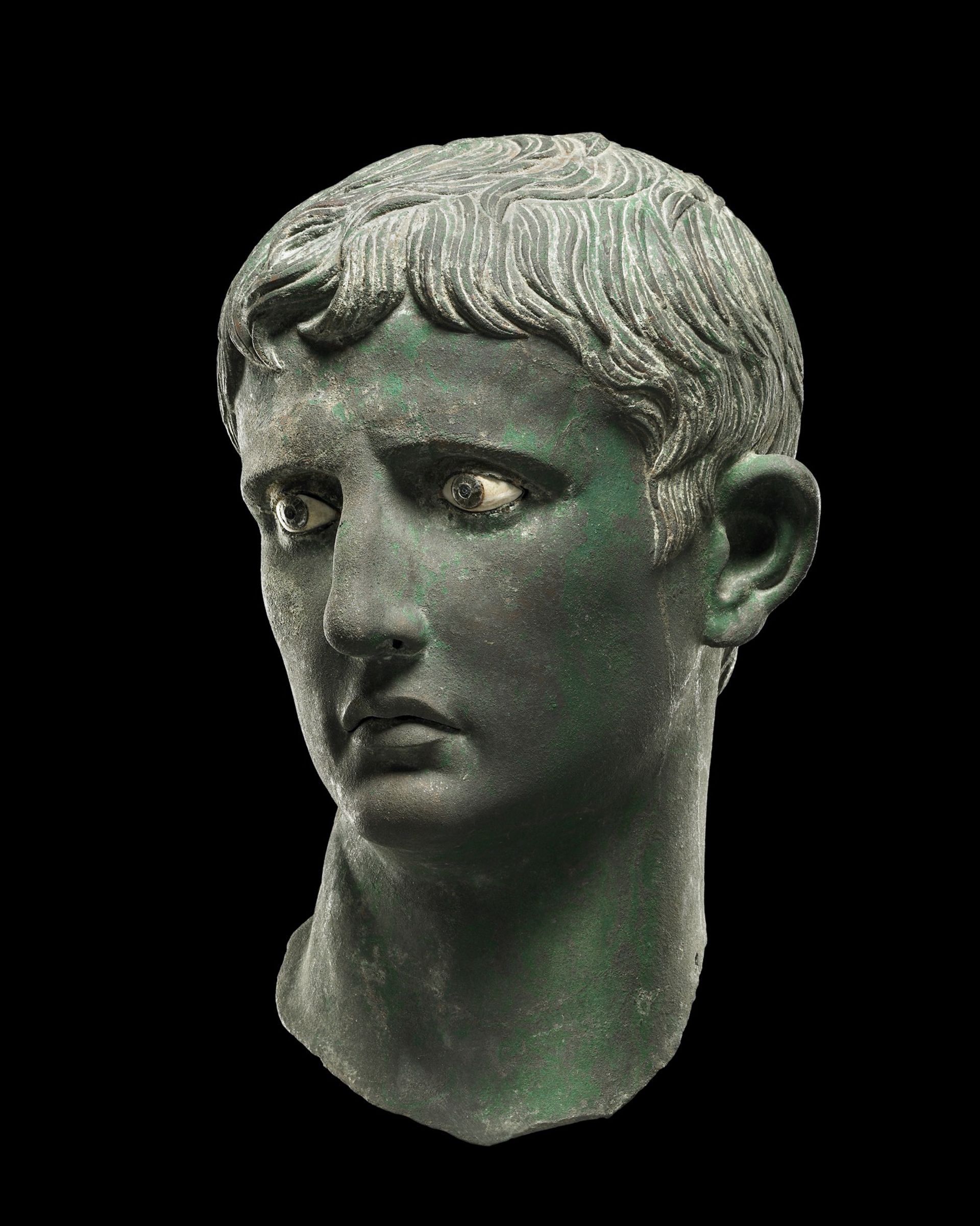

Beyond the Roman era busts of Augustus and Germanicus and a finely carved marble statue of the god Bes, there are few aesthetic showstoppers in the exhibition. There's no CT-scanned mummies, no 3D projections or reconstructions, no epic centrepiece like the warship in the British Museum's recent Viking exhibition. For this show, it is a good decision. As you walk from display to display, what is most enjoyable are the quiet moments spent pondering the significance of everyday objects, or when you spot something oddly familiar, but with an alien twist. A second or third century AD invitation to dine at a feast, sent by a man named Apion to a guest, seems relatable enough, until you realize that he's renting out the temple of the Graeco-Egyptian God Serapis for the event. A child's woollen sock looks like something you could buy at a department store, until you notice the split at the toes, which made it wearable with sandals.

As presented, the 1,200-year story of these three monotheistic religions is a lot to absorb. Unless you plan to spend all day with the exhibition, you need to take in lengthy blocks of information fast. It is a bit like being forced to speed-read a book. And because many of the objects displayed are simple items from daily life (coins, vessels, textiles) or papyri bearing ancient scripts, little can be gleaned of their importance without doing the required reading. This can be overwhelming. It means you might need to walk through the exhibition twice: one time to read the texts as a primer, and the second time to concentrate on the objects with your newfound knowledge.

This is not criticism. It is simply that this is not an exhibition to rush through during a rainy hour in central London. Egypt: Faith After the Pharaohs is more akin to a deep, contemplative character drama than a flashy, fast-moving Hollywood CGI-fest. It demands a lot of the viewer—perhaps more than it should—but rewards those with a slow pace and careful attention.

Garry Shaw gained his doctorate in Egyptology from the University of Liverpool. He is the author of four books, including The Egyptian Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends (2014), and, as a part-time tutor, teaches an online course in Egyptology for the Oxford University Department for Continuing Education.

Egypt: Faith After the Pharaohs, British Museum, London, until 7 February 2016